The dominant neorealist school of International Relations maintains that the actions of states in the international system are primarily determined by the incentives and disincentives established by the international community. However, Andrew Moravcsik has convincingly shown that domestic factors are the most significant determinants of how countries behave on the world stage. All the more reason to consider one internal phenomenon that shapes foreign policy: virtue.

In an article on Saint Hildegard of Bingen, Christian Nikolaus Braun contends that, in the medieval writer’s estimation, “internalizing the Christian virtues is a prerequisite of the good ruler. The virtues take on the function of a safeguard against misrule.”

Recently, the importance of virtue in rulers was widely recalled in conjunction with the vote on aid to Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan in the House of Representatives. Conrad Black was hardly unique in calling Speaker Mike Johnson “an authentic American hero” for risking his post to achieve a vote on the aid packages.

However, more important in a case like that of the United States may be virtue among the electorate. Saint Hildegard emphasized moral fiber in rulers, but in a democracy, the voters are the rulers. Accordingly, the Founding Fathers were keenly aware of the need for a virtuous citizenry if America’s republican “experiment” was to succeed.

John Adams proposed a memorable symbol for this idea, suggesting that the Great Seal of the United States bear the image of Hercules. This was meant to evoke a myth wherein the Greek hero rejected a personified Pleasure, choosing instead to follow Virtue down her more arduous path. According to history professor Thomas A. Foster, Adams held that the story “captured the fortitude needed for the success of individual man but also of the United States, as a collective Republic of virtuous men.”

Theodore Roosevelt likewise extolled virtue, and specifically the willingness to undergo “danger,” “hardship,” and “bitter toil,” in his famous speech “The Strenuous Life.” For Roosevelt, such moral fortitude should be demanded not only of individual citizens but also of the country as a whole. While individual travails had raised the nation’s standard of living and generated extraordinary feats of scholarship, Roosevelt argued that the collective decision not to take the easy path of pacifism had made victory in the Civil War possible.

So how can one foster virtue in a society? To answer this question, it is apposite to try to form a general idea of what virtue is. Much of that word’s classical meaning comes down to self-control or, to use a phrase from economics, “low time preference.” Time preference is the preference for consumption in the present or near future, so its opposite is the ability to delay gratification. At least two academic papers have argued that the lessening of time preference plays a major part in the advancement of civilization.

It follows from David Howden and Joakim Kämpe’s analysis that minimizing arbitrary and unpredictable legislation, reducing crime, and promoting “stable family values” has civilizing effects, the latter because having children allows “for time preferences to extend beyond death.” Sexual mores have a similar effect, whereas inflation increases time preference by discouraging saving.

This implies a few obvious policy prescriptions. Among these, restrictions on public obscenity may be the most straightforward to implement, and the rationale for them is suitably intuitive. As Irving Kristol once wrote, “if you believe that no one was ever corrupted by a book, you have also to believe that no one was ever improved by a book.” Last year, Providence editor James Diddams noted “encouraging signs” in this area regarding age-verification regulations for pornographic websites. Thankfully, the United States is inching towards a ban on TikTok, arguably a more damaging platform for obscenity.

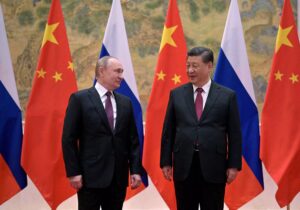

Regrettably, substantial increases in virtue can be undone through immigration, when large numbers of individuals brought in from societies with vastly different moral codes are not assimilated. Multiculturalism and “cultural relativism,” argues Kevin Donnelly, have left “Australia and the West” confronting “an existential threat from enemies both without and within.” Like other aspects of the domestic organization of states, approaches to immigration and integration are not separate from foreign policy. Accordingly, Douglas Murray does not treat them as separate in Neoconservatism: Why We Need It. Murray identifies moral relativism as the enervating force that prevents Western countries both from confronting external foes and from explaining “why an individual or group that desires, or even encourages, the downfall of our society should not remain a part of it.”

Still, to tie this discussion back to Saint Hildegard and her focus on “Christian virtues” specifically, we can mention that religiosity seems to increase self-control. In line with the literature cited above, this can be described as reducing time preference. A 2021 study indicates “that religion obtains its behavioral effects through its intermediate effects on self-control” or, in other words, that religion’s social benefits stem from its power to strengthen people’s restraint.

Fittingly, a 2022 article finds that American Evangelicals are especially likely to view international relations from a perspective which includes “pessimism about human nature and emphasizes national self-interest, protection of ingroup members, and military force.” Those who adhere to this cluster of ideas also believe that peace can only be secured through strength. Simply put, they are right about foreign policy. While members of other Christian denominations score lower on some measures of foreign-policy assertiveness, this tendency does not appear very strong overall; instead, it is the lack of any religious affiliation which “is among the strongest, most consistent predictors of” disagreement with hawkish attitudes.

As we have seen, virtue is an essential driver of sound foreign policy. This is especially true in a democracy, where it has to be all the more widespread. America cannot project power abroad without first cultivating virtue at home.