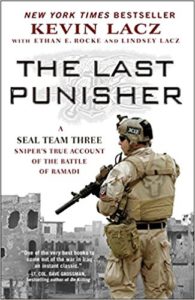

“August 2 was a bad day.” So begins Kevin “Dauber” Lacz’s chapter “Man Down” in his combat memoir The Last Punisher. Lacz served with Naval Special Warfare Group ONE, SEAL Team THREE, as a sniper, breacher, and corpsman on two combat deployments in Iraq. While you won’t find him mentioning it in his book, he earned a bronze star for valor, and two Navy and Marine Corps Commendation medals. He fought like a warrior hero, in a company of heroes. It is right that their story is told.

“Punisher” points to the moniker given to the legendary unit in which Lacz served—along with Chris Kyle, a legend in his own right of The American Sniper fame. Taken from the Marvel gun-toting vigilante of the same name, the Punisher, once a Force Reconnaissance Marine, avenges the violent loss of his loved ones by waging a war against evil. Bearing a white skull emblazoned on his chest, the Punisher “delivers justice to his targets in the form of violent death.” The Punisher’s unwavering commitment to the fight, however much it seems to be without end, is grounded by his time in the service.

Just so, Dauber and his Team members share the same commitments: to their cause, to their nation and loved ones, most especially to one another, and to bringing violent death to evildoers. These commitments, tested on the anvil of war, become one—a composite stronger than its constituent parts. Telling the story of the 2006 Battle of Ramadi, Lacz makes plain just how much such an alloy was needed. Together, and only together, he and his brothers—including Kyle, Mike Monsoor, Ryan Job, and Marc Lee, among many others—were responsible for securing key locations under extreme combat, and pacifying them. The Punishers played a pivotal role in a pivotal battle.

In many ways, “Man Down” is the first of what could be called the two-chapter core of Lacz’s book. It describes the downing of one of his team members—Ryan “Biggles” Job—and the fateful events consequent to it. The sequence is already familiar to anyone who has read American Sniper, for Kyle was on the rooftop where Biggles was hit, and he played a primary role in what followed. Sniper therefore tells the same tale. While particular details conflict between the two books—probably a result of the fog of combat—the primary narrative is tragically the same.

On August 2nd, during a major push, Team 3 had secured a pair of buildings. Lacz and his squad set up on one roof while Kyle and his were on another. Providing overwatch—sniper protection—they gave a security umbrella to the American warfighters clearing the streets below. Suddenly one or several enemy shots shattered the relative calm. Over the radio, Lacz heard a cry from the other rooftop, “Man down! Man down!” A bullet had had ricocheted off Biggles’ rifle, and drove into his face.

Unable to assist from his own location, Dauber describes how Marc Lee, a Team 3 machine gunner, immediatly began burning through hundreds of rounds in a purposeful rage—single-handedly providing cover fire for Biggles’ medevac. Despite their severity, Job would survive his wounds, though he was rendered permanently blind. With the same courage he displayed in earning numerous combat decorations for valor, Biggles would go on to conquer blindness. Among many other achievements, he summited Mt. Rainer in 2008 as part of Camp Patriot’s climbing team. “The summit was amazing,” he said, “even for a blind man.” Job would die in 2009 following a twelve-hour surgery to repair his eye socket, reportedly from a preventable complication. His wife was pregnant with their first child.

The second chapter of our duo-core, “All Stop,” takes up after the successful evacuation of Job back to the combat operations post. Lacz writes:

It took a few minutes to flip our collective switch from demoralized to calculated blood rage. It’s a reflex as old as war; they kill yours; you kill more of theirs…a frontal assault. Violence of action. That was the plan.

The plan would go terribly wrong. Re-engaging the enemy, the Team had just cleared a structure when, as Lacz describes, “a loud burst of enemy machine-gun fire ripped into the first floor below us…and blew out the glass from the window in the downstairs hallway.” Hard after the dreaded cry was heard anew, “Man down!” The voice, Lacz records, was desperate and urgent. “Man Down! We need a fucking corpsman down here now!”

I took three bounds down the stairs and saw my best friend, slumped at the bottom, staring vacantly at the ceiling. Marc [Lee] was down, one leg folded awkwardly under him and his gun off to the side. EOD Nick knelt and returned fire out a window, and as I moved to grab Marc, another burst of intense fire came in. I didn’t wait. I grabbed Marc by his kit and dragged him around the stairwell’s alcove to work on him there.

Lee had been shot through the mouth and shoulder. “I knew Marc was dead before I started working on him,” Lacz writes. “There was nothing I could do to bring him back…An intense gun-fight was playing out around me, and I wanted nothing more than to loose my rage at the enemy. But I had a job to do…I had to be a medic and work on my brother.”

Marc Lee was the first SEAL killed in combat during Operation Iraqi Freedom. A talented soccer player, he attended college and pursued degrees in Bible and Theology, and Law, before enlisting in the Navy with a contract to test for the SEALs. Of Lee’s wife Lacz tells us, “He talked about her endlessly.”

Lee would be posthumously awarded the Silver Star for his actions during the assault. His citation includes this testimony:

During the assault, his team came under heavy enemy fire from an adjacent building to the north. To protect the lives of his teammates, he fearlessly exposed himself to direct enemy fire by engaging the enemy with his machine gun and was mortally wounded in the engagement. His brave actions in the line of fire saved the lives of many of his teammates. Petty Officer Lee’s courageous leadership, operational skill, and selfless dedication to duty, reflected great credit upon him and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. Action Date: August 2, 2006

In obituary reflection on Lee Lacz writes, “We are all brothers. Each life lost over there has its own story, and I’ve even come to learn many of them. The difference between Marc and the other stories is that I loved Marc.”

The Last Punisher gives us a portrait of fighting men. It is not high literature—this could have been written by a frat boy. Indeed, Lacz gave being one a shot before duty called. But while the rhetoric may not be soaring or high-minded, the sentiment in which it revels most certainly is. Lacz unashamedly celebrates the old platitudes—patriotism, duty, love, self-sacrifice, courage—my Lord is there courage! Stones, no, boulders so large not even Hercules could lift them (though, he “could lift a smaller one!”).

Such books are not meant to be read for their literary virtue but, better, for their reminder that virtue exists. To read such works is to recall that our freedom is secured by great men (and women) at both great peril and great price.

I think now of my family having just finished reading aloud J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings—a rare book combining both literary virtue with the veneration of virtue. In it there’s a conversation that passes between Pippin and Merry, two hobbits of the Shire. They discuss the great heroes Aragorn and Gandalf, in whose adventures both hobbits have played an important role. But they confess to one another that they are not of quite made of the same fiber as the great heroes. They are weary of the high adventure. They admit they cannot “live long on the heights.” But, says Merry, “At least we can now see them, and honour them.” He continues:

It is best to love first what you are fitted to love, I suppose: you must start somewhere and have some roots, and the soil of the Shire is deep. Still there are things deeper and higher; and not a gaffer could tend his garden in what he calls peace but for them, whether he knows about them or not. I am glad that I know about them, a little.

It’s an odd segment, in some ways, because the hobbits seems to be talking about Aragorn and Gandalf and the great heroes of Middle Earth but, also, they seem to be talking about some thing—the heights—that stand in contrast to the simple, safe predictability of the Shire. These heights—unlike the firm-grounded Shire—are perilous and exhilarating, and so rarefied is the air of such lofty places that they cannot long be endured by those whose chests are unaccustomed to the harder breathing required there. So is it heights or their fellows of which the hobbits speak?

I suspect it’s both. I think Tolkien means to convey the idea that Gandalf and Aragorn carry in their persons a lofty presence that is palpable, felt by those in their company. In Martial rhetoric, unless I am much mistaken, this is called bearing. In Hebrew, the word we want is “kavod,” which means “respect”. You say it to one you hold in high esteem, who has accomplished something worthy of admiration. The root for kavod comes from the word for weight, or heaviness.

So what’s the connection between hobbits, Hebrew, and the Punishers? Men like Kevin Lacz, Chris Kyle, Ryan Job, and Marc Lee have weight—they have mass, a gravitational pull all their own that rightly attracts our attention, our gratitude, and our respect. And is right that we hear their stories. I am glad that I know about them, if only a little. Kavod!

—

Marc LiVecche is managing editor of Providence. He and his family will remember these fallen this day. Thank you for standing on freedom’s wall.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024