In the first part of my review of the Ken Burns and Lynn Novick PBS documentary “The Vietnam War”, I lamented the absence of voices and perspectives that would give the documentary a sense of proportion as it evaluated the purpose and prosecution of the war. At the end of the documentary, we find, perhaps, the reason for this. “The Vietnam War,” the narrator tells us, “was a tragedy immeasurable and irredeemable.” It appears that the producers, here, are giving away their game. There is no balanced perspective because balance is not to be found in the irredeemable.

But all is not lost, for we are reassured that “meaning can be found in the individual stories” of those who fought—or fought against—the war. Ultimately, this is precisely what we get: a record of what a very limited number of rather select individuals think about the war today. Their testimonies are dispensed in vintage Burns fashion, delivered by poignant voiceovers accompanied by both a stirring—if frequently provocative—narration and by an array of dramatic close-up images and a great deal of archival combat video, much of it riveting. The Burns brand has consistently meant wonderfully high production values, a packaging that, here, helps promote what at least appears to be a formidable argument.

And make no mistake, Burns and Novick are presenting an argument. Consider the testimonies of the combat veterans, both American and Vietnamese. The Americans tell us what they remember, not only about their factual recollections of combat, peace demonstrations, casualties and frustrations, but also their views regarding history, geopolitics, and their own ideology and political leanings. The narratives are, therefore, laced with moral evaluations. This is, in principle, fine. But what’s noteworthy is the condemnatory pattern. A composite might run thus:

I remember fighting for my life on some God-forsaken hill in Vietnam. I remember helping to load my buddy on the medevac chopper, I remember protesting the war. I remember dropping bombs on people I couldn’t see. I remember running off to Canada…

It is noteworthy that the US veterans in the series mostly express a negative view of the war, even if they began as supporters. In choosing the veterans they interviewed, Burns and Novick fall back on a common practice of American journalism after Vietnam, which seems to maintain that the only veteran worth listening to is the one who has come to his senses and finally opposes the war. Thus, in the years after Vietnam, John Kerry and other veterans who had turned against the war were media darlings, while those who supported the war were portrayed as somehow inauthentic.

But this is bad history. A 1980 Harris poll of Vietnam veterans revealed that 91 percent were proud of their wartime service; 74 percent enjoyed their time in the service; and, contrary to the notion that the war was inherently unwinnable, 89 percent agreed with the statement that “our troops were asked to fight in a war which our political leaders in Washington would not let them win.” One would think the producers could have found at least a few veterans who supported the war.

The particularly grievous result of all this is that Burns and Novick wrongly reinforce the myth that the US military in Vietnam was an army of unwilling and dispirited draftees—and one composed of an unjust overrepresentation of minorities. But in fact, two-thirds of those who served — and 73% of those who died — were volunteers. With respect to minorities, African-Americans comprised 13.1% of the draftable age group, 12.6% of the military, and 12.2% of the casualties.

The worst case of selective veteran testimony is also, consequently, perhaps the low point of the documentary. Merrill McPeak, an Air Force pilot during the war, praises the plucky North Vietnamese and states point blank that America was on the wrong side of the fight. This represents but one example of the documentary’s continual assertion of a moral equivalence between the US/South Vietnam and the Vietnamese Communists. This equivalency is specious. To a candid observer, I would think the relative morality of the respective sides—represented in the US case by what we fought to prevent—could easily be reckoned by the final outcome of the conflict.

The core goal of the Vietnamese communists was to unify Vietnam under a communist government. The goal of the United States was, simply, to prevent this; to avert the fall of the Saigon government to a communist insurgency. In the aftermath of the communist victory in 1975, two million Vietnamese fled their country—mostly by boat—with thousands losing their lives in the process. Inside Vietnam, a million of the south’s best young leaders were sent to re-education camps; more than 50,000 were executed or perished while imprisoned, and others remained imprisoned for as long as 18 years. When it came to everyday concerns such as education, employment, and housing, the communists established a system that punished those who had supported the Saigon government and the United States. Such reprisals extended to their families as well.

Beyond the morally divergent war aims, the two sides also differed morally in their conduct of the war. To its credit, the documentary acknowledges the communist massacre in Hue during the Tet Offensive, although it is given much less attention than the American atrocity at My Lai. There is, of course, no question that US troops committed atrocities. Between 1965 and 1973, 201 Army personnel and 77 Marines were convicted of serious crimes against Vietnamese. Naturally, for a number of reasons many crimes in war go unreported so it’s safe to suggest that more atrocities were committed than reported or tried. But even such a severe critic of American actions in Vietnam as Daniel Ellsberg rejected the idea that events like My Lai happened on a daily basis or were a matter of policy:

My Lai was beyond the bounds of permissible behavior, and that is recognizable by virtually every solider in Vietnam. They know it was wrong…. The men who were at My Lai knew there were aspects out of the ordinary. That is why they tried to hide the event, talked about it to no one, discussed it very little even among themselves.

Atrocities committed by Americans in Vietnam were, with the exception of My Lai, actions taken by individuals or small groups. All were in violation of standing orders. The US rules of engagement were, according to Telford Taylor, formerly chief counsel for the prosecution at the Nuremberg trials and a critic of many aspects of US Vietnam policy, “virtually impeccable.” Indeed they were so restrictive that they evoked a great deal of criticism from members of Congress appalled at the disabilities placed on American units.

The fact is that fighting a well-trained enemy who operates in highly contested populated areas where civilians often assist the other side is the most difficult form of warfare. The atrocities committed by Americans in Vietnam can be generally attributed to what the Greeks called thumos, or spiritedness, which manifests itself as righteous indignation or anger. The frustration of troops fighting under the most difficult conditions, against a frequently unseen enemy, the loss of friends to mines and booby traps, sometimes planted by ostensible noncombatants, led them on some occasions to vent their anger on Vietnamese civilians. While this does not excuse barbaric behavior, it does help explain it.

In contrast to the random criminal violence of independent America acts is the systematic use of terror as a matter of policy by the Vietnamese Communists. Yet so widespread was the belief that Americans were conducting a barbaric war that many opinion-makers refused to believe, despite the irrefutable evidence, that the wholesale slaughter of civilians in Hue during the Tet Offensive—more than 2,000 locals systematically executed during the brief communist takeover of the city—was perpetrated by the Communists.

The most important distinction is that the deliberate killing of innocent civilians was a crime in the US military, a crime that earned punishment. The United States accepted responsibility for My Lai, something the communists—who deliberately killed thousands of civilians as a matter of policy—have failed to do regarding their evils.

One final complaint. It is significant that Burns and Novick ignore the changes that occurred after 1968. Too many historians who mention the period after Tet 1968 emphasize the diplomatic attempts to extricate the US from the conflict, treating the military effort as nothing more than a holding action. But as William Colby observed in a review of Robert McNamara’s disgraceful memoir, In Retrospect, by limiting serious consideration of the military situation in Vietnam to the period before mid-1968, historians leave Americans with a record “similar to what we would know if histories of World War II stopped before Stalingrad, Operation Torch in North Africa and Guadalcanal in the Pacific.”

To truly understand the Vietnam War, it is absolutely imperative to come fully to grips with the years after 1968. As Bob Sorley wrote in his book, A Better War, a new team was then in place. Shortly after the Tet offensive, Gen. Creighton Abrams succeeded Gen. William Westmoreland as commander, US Military Assistance Command–Vietnam (USMACV). He joined Ellsworth Bunker, who had assumed the post of US ambassador to the Saigon government the previous spring. Mr. William Colby, a career CIA officer, soon arrived to coordinate the pacification.

Far from constituting a mere holding action, the approach followed by this new team constituted a positive strategy for ensuring the survival of South Vietnam. Ambassador Bunker, Gen. Abrams, and Mr. Colby

brought different values to their tasks, operated from a different understanding of the nature of the war, and applied different measures of merit and different tactics….as they raced to render the South Vietnamese capable of defending themselves before the last American forces were withdrawn…[in] the process they came very close to achieving the goal of a viable nation and a lasting peace.

The defenders of the conventional wisdom reply that Mr. Sorley’s argument is refuted by the reality that South Vietnam did in fact fall to the North Vietnamese communists. The documentary repeats the claim that the South Vietnamese lacked the leadership, skill, character, and endurance of their adversaries. Mr. Sorley acknowledges the shortcomings of the South Vietnamese and agrees that the US would have had to provide continued air, naval, and intelligence support. But, he contends, the real cause of US defeat was that the Nixon administration and Congress threw away the successes achieved by US and South Vietnamese arms.

The proof lay in the 1972 Easter Offensive. This was the biggest offensive push of the war, greater in magnitude than either the 1968 Tet offensive or the final assault of 1975. The US provided massive air and naval support. While there were inevitable failures on the part of some ARVN units, all in all, the South Vietnamese fought well. Indeed, having blunted the communist thrust, they recaptured territory that had been lost to Hanoi. Finally, so effective was the eleven-day “Christmas bombing” campaign (LINEBACKER II) later that year that the British counterinsurgency expert, Sir Robert Thompson exclaimed, “you had won the war. It was over.”

Of course, three years later, despite the heroic performance of some ARVN units, South Vietnam collapsed against a much weaker, cobbled-together NVA offensive, mainly because of an act that still shames the United States to this day: the congressional decision to cut off military and economic assistance to South Vietnam. Subsequently, President Nixon resigned over Watergate and his successor, constrained by congressional action, defaulted on promises to respond with force to North Vietnamese violations of the peace terms.

So what are we left with? When it comes to assessing the lessons of Vietnam, Burns and Novick again come up short. At the end of the program, one of the interviewees, a lieutenant who fought in Vietnam in 1965, serves up what is presumably the documentary’s final judgment: “We have learned a lesson . . . that we just can’t impose our will on others.” This is false. It the very business of war to impose one’s will upon the enemy. History has shown time and again that this is, in fact, entirely possible. Indeed, if the purpose of war is, ultimately, to achieve a better, more just peace, then the imposition of one’s will against the enemy is not just possible, but morally appropriate. There is no other reason to resort to war at all.

Pace Burns and Novick—and that lieutenant—what we should have learned from Vietnam are lessons that apply to all wars. It is necessary to have some clarity concerning the goals of the war, since they are fought for political objectives. Strategy must link those goals to available resources and be constantly adapted to shifting circumstances. Any strategy must take account of the enemy, for, as the adage goes, any plan that depends on an enemy’s cooperation is bound to fail. Finally, defeat in war creates serious consequences for the defeated and its allies.

We can learn from history. We can learn from previous wars. But we need to ensure that we are learning the right things. As that lieutenant’s comment illustrates, too many of the alleged “lessons” of Vietnam are not.

According to Burns, the documentary sought neutrality by “only call[ing] balls and strikes.” As someone on one side of the Vietnam age-group divide, it is my opinion that it failed to do so.

—

Mackubin Thomas Owens is a Providence contributing editor, the dean of academics at the Institute of World Politics, and editor of Orbis. He is the author of US Civil-Military Relations After 9/11: Renegotiating the Civil-Military Bargain.Mac is a Marine Corps veteran of Vietnam, where as an infantry platoon and company commander in 1968-1969, he was wounded twice and awarded the Silver Star medal. He retired as a Colonel in 1994. Follow him @MacOwens4

*Parts I & II of Mac Owen’s review are drawn from a larger essay that will appear in print in the Winter 2018 print edition of Providence, featuring additional essays on the Vietnam War–among other great reads. Be sure to subscribe today to get your copy in the mail.

—

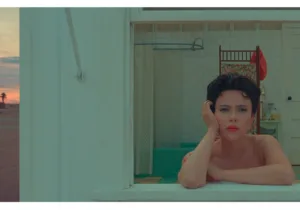

Image: Wife of victim of Tet Offensive, Hue, Vietnam, by Horst Faas 1968. The Massacre in Huếis the name given to summary executions and mass murder perpetrated by the Viet Cong during the Battle of Huếthat began on January 31, 1968 and lasted a total of 26 days. During the months and years that followed, dozens of mass graves were discovered in and around Huế. Victims included women, men, children, and infants. The estimated death toll was between 2,800 and 6,000 civilians and POWs. Victims were found bound, tortured, and sometimes buried alive. Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024