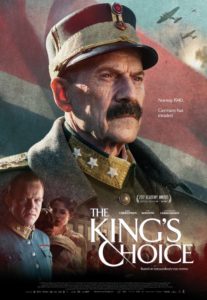

The King’s Choice is a marvelous and moving new Norwegian film about the king who defied the Nazi invasion of his nation, with important lessons about honorable statecraft and Just War teaching.

Haakon VII was nearly 70 and in ill health when Germany invaded Norway in April 1940, after WWII had begun, but before Germany invaded France. He was a Danish prince whom Norway democratically anointed as king at their 1905 independence from Sweden. Hitler sought neutral Norway’s conquest for its mineral wealth, especially iron ore, and to prevent its alignment with Britain and France.

As the King and his government retreated north from the advancing Germans, Hitler mandated the infamous Quisling, head of Norway’s tiny fascist party, and whose name became synonymous with treason, become Norway’s puppet premier. Germany offered Haakon peace if he acceded to Quisling. As a carefully constitutional monarch he deferred to his government, some of whose members favored accommodating the Germans, but declared he would abdicate if Quisling were recognized. Norway’s leaders rallied to their King.

Haakon’s courage ensured Norway would actively defy the invasion longer than any of Germany’s victims, and would continue to resist with a government in exile. (His brother King Christian X of Denmark quickly surrendered to German invaders.] The film shows Haakon initially befuddled and irritated by his son Crown Prince Olav’s prodding for aggressive leadership. But as the royal family retreats farther north, often under German fire, at one point fleeing the Luftwaffe by running into a snowy forest, the King becomes steely, especially after meeting with a German envoy.

In his uniform as an aged chieftain Haakon resembles France’s Marshal Petain, whose example of surrender and collaboration the King could have easily replicated. Instead he would lead Norway’s doughty resistance, at first from the frozen north, and then from Britain, inspiring Norway with BBC broadcasts.

Hungarian historian John Lukacs noted that in 1940 as Haakon and other exiled crowned heads decamped to London:

Four times in six weeks King George and his queen had driven in the evening to Victoria Station, to greet the fleeing monarchs and presidents of Europe with dignity, sympathy, and solicitude. The German air attacks had not yet begun, and the sky was enormously blue in London, unlike those black clouds that had risen from the fires of Bergen, Rotterdam, Antwerp. In the white rooms of London hotels these royal persons of Europe were surrounded by gentleness and courtesy, by the fading flowers of a civilization. They had come to be thus received in its then last island house.

These “bourgeois monarchs of Northwestern Europe” represented the “central cluster of decency” in a world gone mad, Lukacs noted.

Haakon, as part of that decency directed his country’s underground resistance, whose saboteurs notably helped destroy the German heavy water project in Norway in support of a Nazi atomic weapon. His BBC speeches often broadcast from the Norwegian Lutheran church in London, where the King and his kindred worshipped, recalling Churchill’s observation that the enemy they opposed “spurns Christian ethics [and] cheers its onward course by a barbarous paganism.” At war’s end the Norwegian royal family returned triumphantly to their liberated country.

The courage of Haakon to defy Nazi Germany in the twilight of his life, while carefully even in crisis deferring to his own nation’s constitution and democratic principles was a masterful demonstration of honorable and valorous statecraft by a Christian monarch. When a young soldier promises fidelity to him, Haakon reminds him of his own motto: “We give our all for Norway, not the king,”

Haakon’s military resistance was also a demonstration of prudent Just War decision making. Norway waited until German warships were literally offshore before blasting away. The retreating government conscientiously received the peace offers from the German invaders, who claimed they were protecting Norway from Britain and France. Norway replied to the initial German demand by asserting its sovereignty and quoting Hitler’s own observation that a nation that won’t fight for its survival doesn’t deserve to live.

The King’s final decision to resist was brave but not reckless. Norway was not alone. British and French forces, at least briefly were in Norway, and Norway had allies enabling potential ultimate victory. Just War teaching calls for at least the possibility of success, disallowing the murderous futility of suicidal war. Norway’s strongest ally would ultimately be America, where Haakon’s daughter-in-law and his grandchildren found refuge, even living in the White House with FDR, who was delighted by the attractive, attentive and charming Crown Princess.

In the film’s final scene, the King in London reunites with his grandson whom he has not long seen, and embraces the boy who is now King Harald V, who himself appreciatively attended last September a debut of The King’s Choice, which no doubt flooded him with memories of his heroic grandfather.