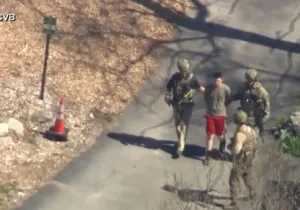

Earlier this week a former Central Intelligence Agency officer suspected of helping China “neutralize U.S. spying operations on its soil” was arrested and charged with violating the Espionage Act.

Here is what you should know about the Espionage Act, one of the most controversial laws in American history.

1. The Espionage Act of 1917 became a federal law on June 15, 1917, two months after the U.S. declared war on Germany. The law gave federal authorities broad powers over internal issues relating to national security. Among the powers granted by the law, the act prohibited willfully making false reports with intent to interfere with the success of the military or naval forces, inciting insubordination, disloyalty, or mutiny in the military, and obstructing recruitment or the enlistment service of the United States.

2. President Woodrow Wilson had asked Congress for the law two years earlier in his State of the Union address on December 7, 1915. Wilson warned there was a small number of Americans who posed a grave threat to national security:

I am sorry to say that the gravest threats against our national peace and safety have been uttered within our own borders. There are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit, born under other flags but welcomed under our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life; who have sought to bring the authority and good name of our Government into contempt, to destroy our industries wherever they thought it effective for their vindictive purposes to strike at them, and to debase our politics to the uses of foreign intrigue.

3. Less than a year after it was enacted, the Act was amended to target certain forms of speech, such as criticism of the government and opposition to the military draft. The amendments, known as the Sedition Act of 1918, included a prohibition against publishing “any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States, or the Constitution of the United States, or the military or naval forces of the United States.” (Congress repealed these amendments on December 13, 1920.)

4. Although it wasn’t authorized by the Act, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson took it upon himself to bar mail from countries engaged in the Great War and prohibited the mailing of radical pamphlets, such as Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth and Max Eastman’s The Masses. Burleson considered himself judge and jury in what was considered “seditious” material. “The instant you print anything calculated to dishearten the boys in the army or to make them think this is not a just or righteous war—that instant you will be suppressed and no amount of influence will save you,” Burleson told an interviewer.

5. During World War I, Charles Schenck, secretary of the Socialist Party of America, mailed circulars to draftees urging them “Do not submit to intimidation” and advising peaceful petitioning to repeal the Conscription Act. Schenck was charged with conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act by attempting to cause insubordination in the military and to obstruct recruitment. The Supreme Court upheld the conviction and decision, as delivered by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., included the famous statement:

The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic… The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.

6. In 1951, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were convicted and sentenced to death under the Espionage Act for heading up a spy ring that gave technology secrets—including information on the atomic bomb—to the Soviet Union. In denying clemency, President Dwight D. Eisenhower said, “I can only say that, by immeasurably increasing the chances of atomic war, the Rosenbergs may have condemned to death tens of millions of innocent people all over the world. The execution of two human beings is a grave matter. But even graver is the thought of the millions of dead whose deaths may be directly attributable to what these spies have done.” The Rosenbergs were the only civilians sentenced to death under the act during the Cold War era.

7. While working for the RAND Corporation, Daniel Ellsberg helped produce a top-secret report ordered by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara entitled “U.S. Decision-making in Vietnam, 1945-1968.” Ellsberg and a colleague made a secret copy of the 7,000 pages known as “The Pentagon Papers,” and leaked it to the New York Times. Ellsberg was charged with violating the Espionage Act, but his case was dismissed because of “improper government conduct”—including illegal wire-tapping—by the Nixon administration.

8. Because of numerous arrests for violations of the Act, the American press dubbed 1985 the “Year of the Spy.” Among the eight major cases that year were convictions of U.S. naval officers John Anthony Walker, Jr. (convicted for spying for the Soviet Union) and Jonathan Jay Pollard (convicted for spying for Israel). There were so many spies arrested during the 1980s—including 12 in 1984 alone— that the FBI dubbed it the “Decade of the Spy.”

9. Since 1945, the Espionage Act has been used 11 times to prosecute government employees who shared classified information with journalists. Out of those 11, seven took place during the Obama administration. Those convicted include Bradley (Chelsea) Manning, a 22-year Army Private who gave classified material to WikiLeaks, and Edward Snowden, an NSA contractor who leaked documents about the NSA’s secret surveillance programs.

10. In the most recent alleged violation of the Act, a former CIA agent named Jerry Chun Shing Lee is charged with unlawful retention of national defense information. According to court documents and the Department of Justice, in August 2012, Lee and his family left Hong Kong to return to the United States to live in northern Virginia. While traveling back to the United States, FBI agents conducted court-authorized searches of Lee’s hotel room and luggage, and found that Lee was in unauthorized possession of materials relating to the national defense. Agents found two small books containing handwritten notes that contained classified information, including true names and phone numbers of assets and covert CIA employees, operational notes from asset meetings, operational meeting locations, and locations of covert facilities.

—

Joe Carter is an adjunct professor of journalism at Patrick Henry College, an editor for several organizations, and the author of the NIV Lifehacks Bible.

Photo Credit: Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, separated by heavy wire screen as they leave U.S. Court House after being found guilty by jury. By Roger Higgins, via Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024