It must be said that the success or failure in recapturing Guadalcanal Island, and the vital naval battle related to it, is the fork in the road which leads to victory for them or for us.

Quote taken from a Japanese document captured during the Guadalcanal Campaign[1]

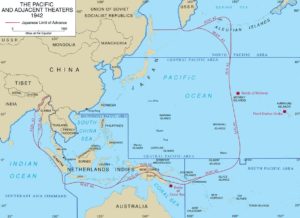

In the aftermath of America’s victory over the Japanese fleet at Midway, Washington was content to fight a defensive war in the Pacific while focusing its utmost energies on toppling Hitler. Admiral Ernest King, Chief of Naval Operations, generally agreed with this strategy, but he also knew reducing the Pacific Theater to a mere holding action would drastically raise the costs of eventual victory. King pushed for some form of offensive to build on the momentum of Midway, and he received a significant boost when word arrived that Japan was constructing a large airfield on Guadalcanal, the largest of the Solomon Islands.

Resting just east of New Guinea and north of Australia, the Solomons could hardly have been a greater strategic prize in the Pacific War. From their bases on these islands, Japan threatened not only vital Allied supply lines but Australia herself. King managed to secure authorization for an operation to retake the islands and shut down the Japanese airfield. The mission, however, still took a backseat to operations in Africa, and the American forces dispatched on this mission would have to make do on limited supplies, firepower, and men. The United States’ vast manpower and material superiority that the Japanese so feared came into play very late on Guadalcanal, but even then deployments were under strict limitations, making this one of the most evenly-matched campaigns of the war.[2]

On August 7-8, 1942, America staged its first amphibious operation since the Spanish-American War, planting troops on Guadalcanal. While the Marines took the incomplete Japanese airfield relatively quickly—renaming it Henderson Field after a fallen hero from Midway—holding it in the face of relentless Japanese counterattacks taxed their endurance to the breaking point. The day after the landings, Admiral Frank J. Fletcher made the appalling decision to withdraw his carriers, and transports followed suit, leaving the Marines without air support, adequate supplies, or even their full numbers—the transports rushed to get away even before the entire Marine contingent had been unloaded.[3]

A greater disaster followed on the night of August 8-9, when what remained of the American navy suffered a humiliating defeat to an inferior Japanese force. In a span of half an hour, four heavy cruisers were blasted to the bottom of the sea, while over 1,200 Americans lost their lives. King later called it “the blackest day of the whole war.”[4] Yet the defeat at what was soon dubbed the Battle of Savo Island was far from total. The Americans, though bloodied and undermanned, were entrenched on Guadalcanal.

For the next six months, both sides fought a series of inconclusive actions. The US Navy delivered supplies during daytime operations, while Japan shored up its forces with night runs.[5] In October alone, Japan managed to land on Guadalcanal over 15,000 troops who, combined with constant aerial bombardment, made life hellish for the Americans at Henderson Field. In addition to the toll of bombs raining down day and night, the men on Guadalcanal had to battle the elements and quickly learned to curse the muggy jungle and consequent swarms of mosquitoes.[6] For every casualty from combat, five were laid up with malaria.

Nevertheless, the Marines managed to secure Henderson Field and, joined by Army units, began counterattacking in November. The dense jungle terrain meant that combat happened up-close, with some enemy positions remaining invisible to advancing American units as little as 50 feet away. The defenders fought with ferocious tenacity; it took over three weeks to secure a single position at Mount Austen. Once the campaign was over, the 1st Marine Division needed a full year to rehabilitate sufficiently to be used in combat again.[7]

Meanwhile, any realistic chance for a Japanese victory ended on November 12-15, during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. This savage fight blunted Japan’s effort to land a massive influx of reinforcements.[8] Although Japan managed to get some 3,000 troops ashore, the great bulk of its fighting force and their supplies never reached the island, and a massive offensive against Henderson Field planned for late November had to be canceled. Fighting dragged on for another two months, but by now the US Navy clearly had the advantage, while the Japanese contingent on land began to succumb to lack of supplies and near-starvation.[9] In late January 1943—75 years ago last month—Japan finally accepted the inevitable and staged an impressive evacuation, slipping some 11,000 soldiers off the island and past the American navy undetected.[10]

Guadalcanal launched the Allied counteroffensive in the Pacific. As with the Japanese navy at Midway the previous summer, it marked a turning point in the war by shattering the sense of invincibility that pervaded Japan’s army. “The vaunted Japanese army, which had rolled over Malaya, Hong Kong, the Philippines, and Burma, had been stopped”; “the Americans…had shown that Japanese attacks were not irresistible, and in the long jungle slugging matches, it was the Japanese—not the Allies—who finally gave out.”[11]

Yet if Guadalcanal foreshadowed the ultimate Allied victory, it also proved how difficult that triumph would be. It took six long, grueling months to oust Japan from the island, making clear to all ranks that every inch of the road to Tokyo would be bought with grit and determination—and paid for in blood. Still, in the final calculation the most significant lesson of Guadalcanal was not Japan’s doggedness, but America’s. At the heart of Japan’s strategy in the Pacific was a belief that America’s resolve was weak and her ability to absorb casualties would be easily exhausted. After Guadalcanal, only the most delusional Japanese could have entertained such a notion.

—

Thomas Sheppard holds a doctorate in military history from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He currently lives in Washington, DC, where he is writing a book on civil-military relations in the early American navy.

Feature Photo Credit: The US Navy aircraft carrier USS Wasp (CV-7) burning and listing after she was torpedoed by the Japanese submarine I-19 on September 15, 1942, while operating in the Southwestern Pacific in support of forces on Guadalcanal. Source: Naval History & Heritage Command, via Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Quoted in Samuel Eliot Morison, The Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1963),

[2] Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II 2nd ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 341-342; Morison, Two-Ocean War, 164-165.

[3] Weinberg, World at Arms, 342.

[4] Quoted in James D. Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal (New York: Bantam Books, 2011), 62-89.

[5] Morison, Two-Ocean War, 183.

[6] Robert Leckie, Helmet for my Pillow (New York: Nelson, Doubleday Inc., 1957), 51-125.

[7] Weinberg, World at Arms, 344.

[8] Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno, vividly portrays the experience of the naval battle in all its brutality.

[9] Morison, Two-Ocean War, 208-209.

[10] Weinberg, World at Arms, 343-344; Morison, Two-Ocean War, 212-214.

[11] Spector, Eagle Against the Sun, 218.