J. Daryl Charles’ lecture at Christianity & National Security 2023.

J. Daryl Charles discusses justice, neighborly love, and great power competition. The following is a transcript of the lecture.

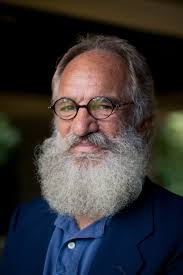

Thank you, Eric. Perfectly, our next speaker Eric already described to you Daryl Charles who is co-editor of his book on just war and Christian traditions and is himself a prolific scholar and expert on just War Christian realism and many other topics and he has a beautiful white beard which makes him very distinguished.

Daryl Charles would you please come forward? Andy has passed out so be watching for those. Daryl, thank you.

All right, thank you, Mark. Yes there is a one-page handout being circulated. Sounds very old school does, it not? Okay uh don’t fold it up and use it as a projectile headed my way uh use it to roll cigarettes if you don’t want to take notes in any case yeah.

Well, thank you very much Mark and uh it’s a delight uh to be here with you this afternoon. It’s hard to believe three months ago, we arrived at the year and a half mark (can you believe it?) of the war in Ukraine. No one would have thought that it would be possible that this former Soviet satellite state just over what 40 million people in number whose sovereignty and territorial Integrity were acknowledged back in 1994 – I’ll have another illusion to that in a minute – and whose Parliament ratified a constitution in 1996 would have survived over a year and a half of bombings and Russian attempts at obliteration by barbaric forces.

Given Ukraine’s remarkably stubborn resistance to this unjust war, and it is wholly unjust by any and all moral measurements therefore demanding our involvement in some way, perhaps then we have become dull to the war’s meaning and global significance.

When the war is being covered in news and Analysis today you will never, never find any mention whatsoever of the 1994 Accord: The Budapest Memorandum. Is that familiar to anybody in this room? Probably to few of us – several but not many – which in fact promised Ukraine’s independence.

I refer here to The Budapest memorandum that was signed by four powers. Guess who they were. The Russian Federation, Ukraine, the UK, and the US. At the time Ukraine exchanged its independence by giving up what was at that time the world’s third largest nuclear arsenal. By the way, guess where that arsenal went, huh?

“Therewith the signatories agreed to respect,” this is the language of the Budapest memorandum “respect the independence of the existing borders of the Ukraine.” It seems to me important questions confront those of us in the West, particularly Great Britain and the US.

Was The Budapest memorandum a political, was it a moral, shall we say, responsibility? And do we was it both and do we as a signatory, basically, have the responsibility of standing to that commitment or are we simply free to ignore it walk away and allow Ukraine on her own on her own simply to disappear?

Mr. Putin is committed to a drawn-out war. We know that he knows that we lack the resolve. Surely in 2023, many Americans – not all, but many – have doubts about why the US should be concerned about a country of barely over 40 million – well, that number is decreasing – whose direct significance to us is not uh political or military.

Let’s take care of our own business at home. I mean just in the last couple days of course even

Republican Senators wrote Mr. Schumer and Mr. McConnell saying, by the way, in the

aid package to Israel uh let’s not include Aid to Ukraine. But President Biden addressing the Indo-Pacific region leaders in May of last year, you may recall, acknowledged that the US would involve itself directly and Military in Taiwan should China be intent on denying the Island’s sovereignty.

Now, by the way, I have my doubts as to whether the US would actually put troops and weapons in the way of China. We can argue about that a conflict, by the way, which is projected to at latest uh confront us in the year 2027.

Of course, uh Xi Jinping uh, sent out uh basically a threat reminding us a year ago uh that uh we’re playing with fire if we dare intervene but allow me to say this and I’ll ask a in the form of a question. Will a nation that won’t help defeat Ukraine now help in the way of an unjust invader put soldiers and necessary weapons in China’s way?

In the next couple years and then of course in the week following Hamas’s crimes against humanity, President Biden declared the US commitment to stand with Israel.

My argument this afternoon, despite Mr. Biden’s record on foreign policy, and that’s not my purpose for being here, is that the US must connect the dots between Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan.

The three are connected as priorities. They do not, I repeat they do not compete. The growing global disorder is, of course in part not fully but in part, a result of the US’s shameful withdrawal from Afghanistan, which has served to embolden all rogue regimes around the globe.

But in my view, Afghanistan is merely emblematic. As former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates has observed, the US finds itself in this uniquely treacherous position facing aggressive adversaries yet without the unity and strength to deter them now.

Permit me to press Mr. Biden’s logic, uh, that used in previous statements concerning Taiwan and Israel apply them to Ukraine, whose very sovereignty and territorial integrity – that’s the language of the memorandum – was promised.

What has released us, I ask, from this obligation? Politically or morally published comments by Kremlin advisers indicate that as early as 1997, war was projected should NATO expand and include Ukraine within its orbit and indeed in 2014, Putin decided to annex Crimea and wage war through Russian proxy elements in eastern Ukraine, the beginnings of which one could argue were in 2008.

Clearly, Putin was boldened by the West’s nonresponse in 2014. Clearly in addition more recently too with our feckless withdrawal from Afghanistan moreover Putin has made it quite clear in public comments both past and present that Ukraine represents a war against

the West and we in the West forget or ignore the fact of its public proclamations namely, were Ukraine to seek NATO membership she would exist no more.

Recall in this regard the number of former Soviet satellite states that are now members of NATO. I can think of eight or nine right off the bat: the three Baltics, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, the Czech Republic…

How many is that? That absolutely gulls Mr. Putin, who publicly has called the breakup of the Soviet Empire as the, these are his words, the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.”

So, there’s no question as to what the goal might be there. Illusion or delusion, the need for a realistic and responsible foreign policy in the part of the US with a deterrent threat cannot be overstated. For three decades, the US and Western nations have engaged in what naively in a policy of appeasement and the truth is that without the US, Europe will not provide Ukraine with what she needs to win the war.

I’m not suggesting that there’s no help there, that there’s not been, but to win the war, we’ve ignored totalitarian tendencies and our foreign policy prescriptions presuming cooperation rather than competition.

Alas, we are faced with the undeniable fact of what the Cold War never ceased to exist. It is simply assumed new proportions the totalitarian threat merely grew subversively while we slept. Nuclear deterrence, which was needed 60 years ago, is needed today even when we’ve ignored the threat expressed by China, Iran, North Korea, and now totalitarian Russia. And of course, the UN has become a veritable laughing stock, has it not? As rogue nations have thumbed their noses at any and all attempts to restrain nuclear proliferation.

Part two, if you’re following on the outline almost three decades ago and roughly concurrent with the Rwanda bloodbath… Does anyone in the room remember that? Wow.

Political philosopher writing at the time Michael Walzer, celebrated author of just and unjust Wars, argued that the morality of non-intervention as an absolute policy needed to be called into question. While acknowledging that intervening in other nations should always generate yes anxiety and hesitation, he nevertheless questioned whether simply ameliorating the effects of unjust aggression… aggression after the fact, so for example providing medical supplies food shelter and that sort of thing was an efficient response where gross injustice such as attempting to annihilate or subjugate a people group is occurring.

Walter argued human decency requires that nations having the wherewithal to prevent or egregious sociopolitical evil must attempt, in his words, to alter the power relations on the Ground. I would agree just war thinking has developed over the centuries and as Eric so wonderfully capsulated in the last couple minutes, wrestles with these very responsibilities.

It asks us to fuse not divorce justice and neighborly love. What is our duty to those who suffer egregiously? Sorry if I’m uh yelling here I’m bit on a bit of a rant, I realize that…

Do those who have the wherewithal to prevent mass evil such as extermination, gross human rights violations, war crimes really have the moral responsibility to inhibit and punish perpetrators of the unthinkable?

Surely, the leadup to World War II – I so appreciated Eric’s comments a few minutes ago – during which period relatively free nations responded with hesitation if not powerlessness taught us non-negotiable lessons. Now the question is whether we take history seriously or whether we’re at all interested in the lessons of history in our day. Not since the 1930s has the geopolitical threat seem so great as it is today and consider just very briefly for a moment German imperialist designs in the Years 1938 through 40.

The Allied mindset was appeasement. Well Austria is annexed, then Czech Republic, then Poland falls… The low countries literally fall in weeks, doorway had of course, and then France in 1940 outside of Great Britain wherein attitudes of appeasement reigned with a few exceptions, Churchill being one.

No one could counter the totalitarian threat and as I speak this afternoon of course Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea are watching and taking notes. Why are they watching and why are they taking notes to see whether there’s risk or reward? Oh, so that we can connect the dots, I think Ukraine and Israel and Taiwan… By the way, uh just in spite of Xi’s comments that yes, the Chinese military should be ready by 2027, US Air Force General Mike Minahan stated in his view the war over Taiwan is likely by 2025. Ladies and gentlemen, that’s less than two years away.

Ukrainian President Zelensky has described Russia as quote “the biggest terrorist organization in the world.” Now before you dismiss that as hyperbolic exaggeration, I would argue that’s not exaggerated one bit but for two important disturbing reasons.

One is the massive number of war crimes committed in this year and a quarter. Since the world began with sadly no international authority whatever competent to be able to adjudicate in matters of international justice, and the fact that Russia and China sit on the Security Council of the UN then make it indeed, uh a joke and a tragic one given the UN’s genesis post World War II.

The second disturbing reality is Russia’s shall we say aggressive and distorting and perverting global influence on other nations in South America, in the Middle East, in Asia, in Africa. Tragically, rogue regimes with nuclear capability have been uninhibited for decades, so we are being forced to rethink and I would argue reaffirm both Cold War and just war thinking that employed strategic, hear me, strategic, and tactical threat of force to deter, not just bluff, but if necessary, counter strategically, tactically both the new terrorist and the nuclear menace.

President Biden’s fears of escalation and foot dragging which have marked US policy really since the beginning of the war are simply emblematic of those of most Western leaders. That timidity, I think, is broad-based our fear of escalation plays perfectly into the hands of Putin, the former KGB operative, yes, who exploits the West’s shall we say self-deterrence with both cunning and barbarism. And precisely this is one of the striking features of our caution. Not deterrence of evil, but self-deterrence in the face of evil.

Part Three. As NATO’s General Secretary Jans Stoltenberg observed at the Munich Security Conference last spring, these are his words, “there are no free risk options. The biggest risk of all,” he warned, “is if Putin wins. That will make the world more dangerous and all more vulnerable.” Ladies and gentlemen, I think he is correct. Just as there was no risk-free option in resisting Hitler and geopolitical evil in the mid 20th Century, there is none today. And again, rogue and totalitarian regimes are watching us. They’re taking notes. Is there a risk or reward? The lesson will reverberate around the world, will it not? The only lesson that matters is this. The invasion was a mistake and Ukraine does not have a right to exist at stake, then it is not merely democracy but human dignity and human civilization.

I think they exaggerate not one iota. Ukrainians are the frontline of the struggle for the Civilized world. A year ago, Stoltenberg publicly praised Ukraine for its resilience, saying that it was possible for Ukraine to win the war and three, later, uh we may acknowledge the truth that this prognostication has less to do with Ukraine’s resolve than it does with ours.

Can the US and NATO members give her what she desperately needs? Can we help her not merely survive oh, another year, but give her what she desperately needs to win a war she did not choose and, by the way, what does winning the war mean? Let me just state categorically three simple things on retaining control.

One, sovereignty over its internationally recognized borders. Two, safety and security from terrorist attacks. Three, justice for the untold victims of the war. Would any nation not want those three? Would we… is their land not theirs? Or is it not, by the way, should Ukraine not be able to defend her own airspace? I ask that not just to be provocative but it’s an honest question. Should she not be able to pro… to defend her own airspace?

From the war’s beginning, both the UK and the US ruled out imposing no fly zones. Do we forget that a year and three quarters later in effect, that told Ukraine “Sorry, you’re on your own?” This is outrageous to help her defend her own airspace especially against a provocative nuclear-capable aggressor. And should she not be given the weapons, the tools, to be able to self-defend? And if not, what does this tell every tyrant, every despotic rulers around the world? “Go ahead and invade. Invade. You’ll get something out of it.”

In my view, Stoltenberg was right. There are no risk-free opportunities. Okay? Let’s just lay our cards on the table. The greatest risk of all indeed is if Putin wins, which will indeed make the world far more dangerous and all far more vulnerable should we not rise to confrontation in face of unjust war in Ukraine. Now that we thereby then encourage Russia’s, shall we say miscalculation, and even greater Russian atrocity in the next three to five years. I’m not a prophet but I prophesy… but we also encourage every tyranny and every despotic regime around the world so it seems to me the options are courage or cowardice, chaos or principal competition.

So, I ask, where is our moral backbone? We can help Ukraine win the war and if we don’t, greater global collaboration is guaranteed in totalitarian aggression. But maybe we need to back up half a step. Why is it we hesitate to counter evil? Perhaps it’s because in Western culture and we in the States have difficulty distinguishing between good and evil, and if people are not going to use that term in their vocabulary geopolitically, diplomatically, it is probably not very popular, but if we’re not going to use that kind of vocabulary, that requires we believe that there is something called evil. No, so why do we hesitate and by the way, while I’m on a rant here, what kind of evil are we talking about?

Uh, let’s be reminded violation of the nation’s internationally recognized sovereignty and territorial integrity in 1994… Approximately 600,000 dead or wounded right now. Again, that’s approximate millions of refugees, millions of widows and fatherless as a result of the war. Deportation… have you remembered this? Tens of thousands of Ukrainian children… destruction of a nation’s civilian infrastructure and untold numbers of crimes against humanity and war crimes…

I asked what is a just response to an unjust invasion and such unparalleled barbarism? Is our fear of escalation well-founded or foolish? The fruit of moral spinelessness… Another question… Does freedom have the responsibility in international affairs to deter, prevent, or geopolitical evil? Just war moral reasoning answers “yes,” we do yet with qualification. However, central to that qualification is proportionality of threat.

The question though is whether we have the backbone to deter sociopolitical evil of. This of course is the challenge before Israel right now, is it not? And here with perhaps a word on deterrence might be in order for decades.

As we all know, there’s been this battle back and forth between social scientists and economists, right, on the matter of deterrence. Social scientists – not all of them, but most of them – have strong skeptical attitudes towards deterrence. It doesn’t work, it’s not effective, it’s not efficacious, it isn’t interesting… that economists in contrast almost all understand deterrence to work. They remind us raise the cost, raise the price a little bit and watch public attitudes change immediately.

Yes, interesting, there are two bottom lines in just war: moral reasoning, one, to sanction coercive intervention against evil, to prevent or alleviate human suffering, do you agree? Number two, to establish moral limits beyond which evil must not reach. In addition to, yes, proportionate response to that evil, but proportionately thrown around a lot these days needs qualifications. Proportionality is not a mathematical formula, okay? It’s not tit for tat. It cannot simply be quantified “this much or that much right.” And as Israel now realizes, it is eradicate. For Israel, proportionality means today eradication of the evil that has produced the current calamity.

As World War II and Hitlerian atrocities remind us, or to use World War II language, it is unconditional surrender. Interesting, just war thinking as it is applied to policy communicates to the aggressor what is forbidden, that is, what will not be tolerated. Ladies and gentlemen, to believe that some things are forbidden and not to be tolerated is to affirm the justice of deterrence which aims to prevent gross injustice. Most people into it, in spite of the controversy between social scientists and economists… Most people, the average lay person, insists that deterrence works. Just ask most parents and simply because let’s say in the criminal justice – I did criminal justice research in Washington before I entered the classroom to teach, so I’ve always had interest in issues of justice, that is a bit of my background…

But just because in the domestic realm in terms of criminal justice, psychopaths will not be deterred and just because in international context, groups of psycopaths or religious fanatics or terrorists are willing to do the unthinkable, that is not repeat, not, an argument against the validity and efficaciousness of deterrence.

No, the character of justice is such whether in domestic or foreign policy matters. It does not acquiess to evil, otherwise it’s not justice. You can call it whatever you want, but it’s not justice, at least classically understood in a fallen world. Hear me. Deterrence, punishment, and retribution are necessary. That necessity does not simply stop because some humans are possessing even dictatorial or despotic power, are abnormally evil.

Justice, properly understood, deters. Period.

Michael Walzer’s question, and I’m rounding the vent here, of whether to intervene or not in a nation’s affairs should always, yes always, produce anxiety and hesitation, and we hesitate for good reasons. No, we do not intervene in every international crisis. No country, and by the way the US is not called to be the policeman for the world, no nation can do that. It’s impossible… That’s an utter geopolitical impossibility.

On the other hand, nations such as the US which have both the political and the moral responsibility to, shall we say, enlist other relatively free nations… They have the responsibility to inhibit sociopolitical evil when and where it occurs. Now, if we don’t know it about…. if we’re unaware of it, that changes things, doesn’t it? But if we have the wherewithal, if we’re aware of it, then in the end those who need rescuing, to use Walzer’s argument, regardless of how late in the game should do so.

Hey, what applies to individuals morally applies to nations. To whom much has been given, much will be required. The US uniquely has the power to determine how quickly the war of attrition in Ukraine ends. Now, while Walzer was speaking of the politics of rescue, Princeton ethesis Paul Ramsey, to whom Eric mentioned a few minutes ago, spoke of what he called a preferential ethics of protection. I like that. A preferential ethics of protection based on neighbor love which is due those people groups who have been victims of unjust aggression. And to illustrate this interestingly, Ramsey was fond of using the Good Samaritan model drawn from Luke 10.

Now, you would argue well he was being unfaithful to the text because Jesus is not teaching it, but Ramsey extended Good Samaritan ethics and asked this question. Had the Samaritan come upon the beating, the mugging, the stripping, the crime, would neighbor-love have required him to physically, violently prevent the crime? Ramsey’s answer was in the affirmative. I began by noting this afternoon that the US was a signatory to the ‘94 Budapest memorandum, by which Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity was assured.

The Russian Federation has violated all commitments undertaken in the accord. Question. Does the US as a signatory have an abiding commitment to help a helpless case? Can we use that? A helpless nation, an innocent nation… Do we have the responsibility to honor that accord?

In fact, that question is raised by ancient wisdom literature, and here I close. This is drawn from Proverbs 24, in which the wise person challenges us. If you faint in the day of adversity, little is your strength. Rescue those being drawn toward death. Hold back those stumbling toward slaughter. If you say ‘but we didn’t know anything about this,’ does not he who weighs the heart consider it? Does not he who keeps your soul know it and will he not render to every person according to his deeds?

I close. Walzer observed that in the end, it’s unreasonable to expect human decency at home in our own cultural context if we do not display decency to those in the international community who truly need it.

Given our commitments to Ukraine in 1994, I argue a response is morally required. Walzer’s argument needs reiterating. The response of relatively free nations, especially the US, is not merely to wait until terrorist tyrannical regimes have executed their vile work and then go in late in the game or after the fact to kind of try to clean up.

When and where evil can be stopped, there’s a moral obligation to stop it. That, by the way, is the just war tradition. Otherwise, we really cannot call ourselves a decent people. Thank you very much.

Q&A:

Okay, far away, and I saw a lot of people lifting stones but take time and then unload. Feel free.

Question: Um I just wanted to begin by thanking you for taking such a clear moral stance on this, and just to affirm what you said. I mean, I follow the opinion polls very closely in Ukraine and they are overwhelming. Numbers of them are going to fight until the end. And so I’ve said from the beginning Russia can’t win but Ukraine can lose, and Ukraine can lose if we cut off support because they just need the weaponry. They have the manpower, they have the will.

The second thing I wanted to say was I really appreciate what you’re doing because it is as a son of reason, it is just tragic to me to see so many of my fellow conservatives just apostasis on this issue. I mean he’s in his grave right now. And so… but I think that one of the problems has been that we’re not articulating things from a US national interest perspective, and so I really appreciate you’re doing that the more you can do the better.

Answer: That’s part of the challenge isn’t it? I agree with you wholly. Thanks for your comments. I agree with you that’s part of the frustration.

Question: Thank you, yes, sir, Jonathan McGee of Grove City College. I’m curious. Do you think that the US has the capacities to supply weapons or directly intervene in Ukraine, Israel and potentially Taiwan? If not, how do you think we should prioritize which theater?

Answer: I just am not sure. No I’m kidding. Uh simple answer: no. At this point, and everybody is reminding us of where they stand politically, uh that we don’t have, we don’t have things in stock… Uh, I’m sure most NATO members would say the same thing, right? So again, we’re not going down the road alone, even when we must take the lead. Okay, that’s my argument, right? We’re not policing the world and we’re not responsible for every geopolitical crisis, catastrophe, but we must take the lead among those nations that have some wherewithal and are relatively free. Now, no one would have thought that among NATO members would be today, what it wasn’t two years ago. Right?

Hey, I’m married to a German citizen, by the way, spent the first four years of marriage living in what at that time was still West Germany, so that gives you an idea bout my age, and part of the stone age. And we forget, I think, or we don’t educate the next generation. We don’t educate them on the just war tradition, a tradition I… I live in Chattanooga, and we’ve got one of the nation’s ten largest rivers flowing through the downtown area and it brings with it life and culture, and so much you know, through the downtown area, but that river winds through several states back and fort, up and down, and manifests itself in so many different shapes and forms; lakes and ponds, right? It’s amazing but it’s the same river wherever you put your toes into it.

Tradition is like a river. The just war, and let’s not call it just war theory, no, it’s not about to change tomorrow. Yeah, we can have our debates. We can argue in charity about what we disagree, but the tradition holds because it’s founded on moral principles. Now whether nations, kingdoms, are as interested in discovering and applying the wisdom of the tradition, that’s the big question, isn’t it? So that’s why those of us who are burdened about a renewal of thinking about just where categories. Just war moral reasoning are so impassioned. The need is great.

Question: I’m a Protestant. I was a convert to natural law. I’m an evangelically minded. I was a convert to natural law when I was doing criminal justice research in Washington. Why? Because I ran into so many Roman Catholics who took their faith seriously and, of course, Catholic social ethics can’t be hidden and natural law thinking is right at the center of that, is it not?

Answer: For generations, Protestants have had the suspicion of and this bias against natural law thinking “no.” This is simply what St. Paul describes as the law written on the heart, that which all people know. Now, do they know all things wholly? Did they know moral truth totally? No, that’s not… that’s not Paul’s position. His position is that they have enough to be held accountable for that reason. He says all are without excuse, yes. So beck to the question, boy, that really was a side note, if I ever heard one, but no.

We don’t have enough, but if we work together, I mean look what South Korea is doing. The way of providing this, that, and the other. Yeah. So if we encourage… If we use our global influence to encourage relatively free nations, we are not doing it alone. Uh, so, uh… but I insist on connecting the dots, you know? But right now, the US isn’t being called to intervene in Taiwan, but I believe it is not to allow Ukraine to struggle along for another year or two. That will be hell. That would be wrong and that would be unprincipled and unjust, so I want to make sure that the dots are not severed, right? I want… I want us to think holistically even when we can have priorities right. Mhm. Yeah. So, uh, yeah. That’s where I stand, and we’re waking up, aren’t we? I mean even secular knuckleheads who were appeasing for 30 decades are now realizing “oh, we haven’t done this, we don’t have this in stock, we’re not prepared for that, we’re not prepared for China, we’re not…” that’s right, yeah.

So the question is do we simply give up? Do we use our influence in a principled way, you know, even if it’s late? In the West’s history, that is not an excuse to abdicate our responsibilities to people groups, to the world. No, we don’t play God. That’s not my argument. But to whom much is given, boy, why do I return to that again and again… to much who’s been given to people groups, who much has been given to nations… To which much has been given, much will be required.

My sister was a servant in the Foreign Service. Part of me wishes I could continue to do criminal justice simply because there was a lot of exciting things going on. It was difficult. I’m a confessional Christian. You don’t find a lot of them in my area, specially with violent crime and capital punishment. Not many people want to touch that. And I grew up, by the way, just anecdotally, I grew up in a Mennonite tradition. Anabaptism, I’m sure my forbears are rolling in their grave in my views on war and peace and how to qualify its necessity. Nevertheless, that’s kind of a strange bit of leading in my own life and I find myself at this day challenged by, saddened by, but mildly hopeful that we can exercise our influence.

And I was just last week in California speaking at a well-known Christian university and at a seminary, and my challenge was not unlike what’s going on in this room today. I was challenging them to go into law, become judges, become attorneys, become diplomats, head for the Foreign Service if you have that burden, become businessmen, yes, become lawyers, become butchers, become bakers and candlestick makers. Don’t just head for quote unquote full-time Christian service, whatever that is. I don’t think that even exists. Head for the world. Be trained and let us exercise as responsible stewards.

To some he gave five to some two, some one great joy over five and two, right? Well done, good and faithful steward. Let’s steward foreign policy. Now not everybody is called to work in matters of foreign policy, that’s not my argument. But let us be willing to go to these avenues of service. They are strategic, are they not? They are so strategic. So that’s another reason why I’m so excited to be here today with all of you. Bless you.

Yeah, any other questions? Unless time has been exceeded… Oh here’s one right beside you.

Question: Yeah, afternoon, sir. My name is White Oliver from Colorado Christian University.

Answer: Great. Lakewood.

Question (cont’d): Yes sir. No, yeah. Now I had a quick question for you. So how would you justify aid to the Ukraine to that portion of the US population that is weary and wary of the forever wars, like what happened in Iraq and Afghanistan? How would you justify that to them?

Answer: Great question, and hey, most of us are products of that kind of thinking, aren’t we? We’re weary, yeah. You didn’t hear me argue that we should be involved in every crisis and that’s where I think just war thinking helps guide us, at least those in leadership, those positions of responsibility. That doesn’t mean we will be guided, but it is a source of wisdom, an enduring wisdom. Remember the river analogy. The river is still the river, so whether we here in the 21st Century and those in the 19th and those in the 4th Century were interested, that’s totally up in the air. So will… will… a culture will… people will be leaders interested in seeking it’s abiding wisdom.

I’m not arguing in any way that the US was right to be in war A, B, or C, okay? And yes, it’s fully understandable why people have become weary and for those who are under my age, and I’m 43, its surely… And I’m… I lie like a rug too… Yeah, but surely there is this weariness. “Are you kidding? We shouldn’t be in country X, we shouldn’t be in country Y,” well here again I have to say we need wisdom in executing foreign policy, just where moral reasoning helps us. It’s not… It doesn’t give us an equation, you know… this equals “yes, go into country X, or here, and here’s how you do it.”

We need discernment. Sometimes everything lines up, but there is something that holds in the way of wisdom and discernment that holds us back. What would that something be? Uh… Could be a million things. But how about if going in, intervening coercively set off such chaos in a region of the world, even though say there was just cause, right… right intention by proper authority… Even if all those things lined up, what if it would send… set up and release hell in that region of the world? That would be credible qualification that might hold that should, I would argue, hold us back, right?

But you have to discern that… Leaders have to sense that, right? So we can’t be Christian nationalists, and say we can’t be Islamists, and say we must keep Church and state separate, yes. That’s the wisdom, I think, of the Christian tradition and the just war tradition rightly understood. That’s where it, I think, has problems, right, fusing Church and state. Yeah.

And it’s not that all Muslims advocate bearing the sword, but it’s interesting that there are enough of traditions within Islam that that is a tendency. And there’s often theological justification for doing that in regions of the world. No… the Christian must resist that but we must also resist the passivity of pacifism.

And I like what George Orwell, who was not on the battlefield, but battled with the pen, of coruse. India at this time was an English territory, so to speak. Orwell wrote often of the… perhaps the most well-known pacifist, non-violent activist of the 20th Century who was that? Mahatma Gandhi. Orwell is very critical of Gandhi, and I write this as one who grew up in a pacifist tradition, and again I love these people, and in some ways they have very strong social conscience, but in matters of force, and here I would distinguish, by the way, between violence, and force. I like what John Courtney Murray had to say: force is that measure of power which upholds law, politics, and civil society. Violence, he defined as that whihc undermines, destroys.

I like that definition, and the just war proponent, I think, honors that distinction. But Orwell’s problem with Gandhi was this, and perhaps some of you have already read this… Gandhi’s view of how to deal with the six million Jews being carted off to death camps… By the way, my father-in-law, I told you that I was married to a German citizen…

My father-in-law served five years of the second World War working for the German bundasban… that’s the German rialroad. My father… not only did that, he served all five years working for the German bundasbond in Poland. That’s where the worst of the death camps were. Not only that, my father… spent five years of the second World War working for the German railroad in Poland, as guess what? A railroad car switcher. Now one doesn’t need much imagination to wonder “wow, Papa, what did you see? What did you experience?” My wife is the youngest of six children. Papa never spoke of his war experiences, and rightly so. And I had a very good relationship with them. I love them, but that perhaps… that’s one reason, I guess, why I’m so passionate about the issues of justice. Yeah. Guess what… guess what Gandhi’s solution was? This was the moral thing to do…

Gandhi advocated that Jews commit as a… as a… collectively as a people group… that they commit suicide to convince the world of Hitler’s madness. Did you hear what I said? This world’s leading nonviolent activist called on Jews to commit violence against… lethal violence against their own bodies to wake up the world’s conscience. I agree with Orwell, who rejected that viewpoint as immoral justice. And neighbor-love, justice, and charity will have nothing of that sort of strategy. Yeah, now hey. There were many things that you could say too by which to praise Mahatma Gandhi, but on that score I’m sorry. That is not justice. That is not charity. Orwell was right to condemn that and we must be as well.

Any others? Okay. Thank you.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024