Here’s how this started:

Well, actually it started many years ago, when Richard and I first started having half-conversations about politics and philosophy and theology over hors d’oeuvres at parties, dinners at Elaine’s Restaurant, and on one memorable occasion, a days-long game of Diplomacy over New Year’s Eve weekend at Mohonk Mountain House. (Actually, I don’t specifically remember whether we talked about this then, but it was a very successful game.)

He’s been a friend of the family since I was in my early teens—he and my dad worked together on a show, The Education of Max Bickford, and at some point somehow he and his family ended up living upstairs from my father and stepmother in our old building on the Upper West Side; I don’t remember what the sequence of events was, but we’ve been mishpocha for a long time.

But this particular conversation started when at the beginning of this past summer he emailed me (off the back of another random email exchange) a Big Deep Civics salvo, and we’ve been going back and forth since then about natural law and public life, God and the Republic, Islam and secularism… and Christianity.

It’s a set of concerns he can’t get away from; he’s cared about this and thought about it for as long as I’ve known him. His nonprofit, The Dreyfuss Civics Initiative, is dedicated to reviving the teaching of civics in schools, and he’s convinced there’s a connection between the decline of commitment to the American civic tradition and the appeal of radical Islam in America and the world.

This is not an essay, nor a set of essays. It is a conversation. It will be published—right up to the point we’ve reached ourselves—in a series of exchanges. And what we both hope is that it will provoke further conversation—with those who see the urgency of the questions, those who are, like us, trying to figure out what’s required of us to survive this strange and challenging time with our cities, civilizations, and souls intact. And we are still trying to figure out: We both—we all—know things now about ISIS that we did not know in June; I’ve found myself trying to understand the history of the different groups that we lump together in the category “Muslim extremist,” and I’ve found that I didn’t know nearly as much as I thought I did. So write us back; help us think together; help us in this attempt to love the truth in good company.

But I’ll let Richard speak for himself…

Susannah Black

Writing from the Blizzard, 1/23/16

———————–

Richard Dreyfuss

to Susannah Black

June 5, 2015

Dear Susannah,

Well, all right, then, how would you go about trying to make people understand that a credible and detailed knowledge of and attachment to the story of the birth of the nation and the enormous widening in political participation it introduced is a) called Civics, b) the intellectual musculature of Enlightenment values and of our founding documents, and c) the only defense against the appeal of ISIS?

I’m seriously asking for your help. This ignorance of civics is the equivalent of what doctors call “invisible killers” like hypertension and bad blood pressure. Our respect for the system of republican democracy is not something handed down by genetic structure or breathed in through the atmosphere. It must be taught. It isn’t. And no one seems to make the connection between the absence of civics and the spiral of civilizational decay we are all aware of. Show me anyone who is happy and cozy and calm about the future of our nation, and I’ll show you a person who thinks of his progeny as his enemy, of our kids as people to hate.

Eviscerating their education, removing both practical self-reliance fostering subjects like Home Ec and Shop, as well as removing the teaching of literature and of values, guarantees that the companies their fathers built will be shredded and that our military will be unreliable. We are already led by a political class that by any measure we care to adopt is a step down. Bought. In the pocket.

We need to teach the methods of assuming and practicing citizenship, the teaching of which were the prime reasons for public schools’ establishment in the first place. Once citizenship was not a word that serious people smirk at. We need the sharply trained intellectual tools that allow for clarity of thought and expression.

You know that the influence of Judeo-Christian theology has become flaccid and lacks spiritual punch; that isn’t true for you personally, but you know it’s true in our world, while in a sickening twist the only spiritual movement being discussed in the public sphere today is ideological thuggery. Western kids are now joining extremist Islam, ISIS.

Civics isn’t taught at all; the Tea Party members in the Congress were born after civics had been removed from the curriculum.They never studied the Constitution or the other founding documents. Civics is a completely pre-partisan issue. It should be supported by all parties and it is cost-free, a point in its favor for those who in our world today are obsessed with all the wrong things. If we don’t revive the teaching of civics from grammar school on, we’re toast way before the end of this century.

Susannah, I’ve never had the ambition to bore you. I admire and appreciate your mind, as you well know. If you tell me I’m nuts or that we have nothing to worry about, I would have to first ask, “Where in our country are civil authority, the real sovereignty of the people, the mobility of mind that allows us to handle anything that life throws at us, the concept of simple accountability: where are kids being taught any of that?” If you can grasp the urgency of what I’m trying to say I’ll do backflips. I’m asking you to help me to re-establish the secular faith of the Constitution, the foundational values that let us be the protector of all faiths; that secular faith, as you must know, isn’t the enemy of any faith: it’s the protector of them all.

We’re the only nation in the history of the world that is bound only by ideas. We have no common class, or caste, or ancestral achievement; no common religion. If we are not taught those ideas, if we do not turn our students into citizens, we are not bound, and I submit that the proof of that is all around us, now, and getting more terrible and fearsome every day. No one in the country can comprehend the stories on the front pages of any newspaper. Not the trillion dollar bailout, not the Middle East, not education, not the lack of spirituality, not the effects of technology…We have a vague sense that the world, that our system is rigged, but we’re strangely incapable of saying or doing anything about it. We are in denial, hypnotized, while the future is beginning to reveal itself in a trail of bloody footprints that leads back to the seventh century. This is what Hitler yearned for, and we believed him enough to do anything we could to stop a return to the worship of Thor and Loki. And today, the thought of comprehending such a thing makes our heads hurt, and we do nothing. If we started to instruct our young in the common sense of due process and holding office-holders accountable, it would be a great start.

Warmest love and regard,

Richard

————

Susannah Black

to Richard Dreyfuss

June 6, 2015

Richard! I love you because you are one of the few people who loves to think about this stuff as much as I do. Not just because of that, though.

Your email is both a late-night rant and a wonderful provocation, and I am very excited to write something in response to it… because I’m very interested in the ways we agree and disagree about both the diagnosis and treatment of the current malaise that, as you point out, is leading kids in America and (far more so) in Europe to join ISIS.

Brief preliminary response:

1. Yes, I agree, we need to take radical Islam at its word just as much as we took Hitler at his. This means getting over a very specific trio of fantasies that prevent us in the West from seeing what’s going on. We tend to assume that the conflicts in the world are caused primarily by economics. This is an assumption fed by the vague marxist-inflected political analysis that you learn how to do in college—not so much in classes in college, as in the conversations that you have late at night. We feel wise when we say that the appeal of radical Islam is due to a lack of opportunity, a lack of jobs, economic inequality between the first and third world or within the Islamic countries. But that’s missing the fact that many of the jihadis are middle class; bin Laden was from one of the richest families in the world; and in any case that’s not what they say is their motivation.

Which leads to the second fantasy: we believe that ideas, fundamentally, don’t matter. But, as Richard Weaver pointed out many years ago, ideas have consequences.

And that leads to the third fantasy: that religion is really a cover for something else, that it’s not itself causal, but is an epiphenomenon—either religious reasons and motivations are reducible to psychology, or they’re reducible to economics. But they’re not. Just as much as philosophical ideas have consequences, theology has consequences.

2. But we need to think carefully about what we have to offer that’s better than Islamism. Is a deracinated liberalism, Locke without Locke’s belief in God as the Father of all men whose fatherhood guaranteed their spiritual equality, strong enough to overcome the appeal of Islamism? Nope. If you are offered a choice of two worldviews, and one (Islamism) affirms the universal spiritual intuition and moral sense of humankind that there really is such a thing as real good and evil, and that humans have souls and not just bodies, and that there is a God who cares how humans behave; and the other (modern secular liberal democracy) denies these universal spiritual intuitions and says that good and evil are matters of convention and preference and don’t refer to anything sold… Islamism is going to appeal.

Because it is wrong about what it believes is good, but it’s right about the fact that good exists. It’s wrong about what it believes God requires of us, it’s wrong about what God is like, but it’s right that he does call on us for our loyalty to him.

3. The American founders said that human life was dedicated to the pursuit of happiness. We don’t know what they meant: we don’t hear this right. We hear the word “happiness” and we think about utilitarianism—the greatest good for the greatest number—with good being really nothing more than pleasure. But Jefferson—surely—had a Greek word in his head when he wrote this: he knew his Aristotle, and he knew that “men everywhere, without exception, pursue happiness:”—eudaimonia, which means wellbeing, the whole and well-lived life of a virtuous man, who does good out of a good heart, does right for right reasons in the right way, and who is—crucially—capable both of citizenship and of the deep friendship which was at the root of citizenship in the Classical world. Such a man was a lover of wisdom—a philosopher—and he was pious.

In Christianity, this wellbeing, this wholeness, is extended into what’s called holiness, and the crucial importance of loving friendships with one’s fellow-citizens is extended into the idea that we were called to loving friendship also with the God of Abraham. The Aristotelian ideal of magnanimity was transformed and deepened by the novel virtue of humility: Christianity taught that God Himself had become humble, and there was no shame in that.

Citizenship, in the central Western tradition that Locke sort of reflected and sort of departed from, was built on all of these ideas, and also on the recognition that citizenship in the City of God is one way that Christ spoke of the highest calling of humanity. We have a deep emotional response to the ideal of citizenship precisely because we are ultimately called to be citizens of the New Jerusalem. We can’t think that any citizenship we have in a City of Man—in America, for example—trumps that. But just for that reason, our ultimate citizenship in the City of God allows us to be better citizens of our cities here, in very specific ways. In the Christian tradition we’re called to loyalty to our place of birth or to our adopted homeland, but not an uncritical loyalty. As Chesterton said, to say “my country right or wrong” is like saying “my mother, drunk or sober.” In other words, yes, it is your country, but because you love it you want it to be better, you want it not to do wrong.

And it’s only with an external measure of the good—a Good that is more than cultural, more than conventional—that we can say that, for example, a law is wrong. If we say that the laws of the Jim Crow South were unjust, we are implying that there is a Law that is above the law. This is what we were talking about at breakfast Upstate a couple of months ago—it’s the natural law that’s above the positive laws made by human legislatures.

What it comes down to is this: we can’t get to the eighteenth century kind of civic commitment and engagement you want without the eighteenth century belief in this natural law.

What I suspect, however, is that there was a weakness at the heart of even this founding-era natural law tradition, or at least of some versions of it—Thomas Paine’s, for example. His version was trying, essentially, to secularize Aquinas. Paine wanted the moral law without a lawgiver: wanted the brotherhood of man without the Fatherhood of God. Jefferson the Deist was in a somewhat better position—somewhat. But all of them—all our founders—were like… I’m trying to think of the best analogy… like people operating a power plant who’ve forgotten the actual science and technology that makes it work. They do routine maintenance because they’ve been taught to; they are able to plug their appliances into the walls and those appliances work, for now, but eventually what’s going to happen is that, because they don’t understand the reason for the maintenance, or the relationship between the power in the wall sockets and the maintenance they do, let alone the actual principles that make it all work, they will decide that the maintenance is a waste of time, and they’ll stop doing it.

That’s what happened with us and civic virtue. The founders knew that virtue was important, but they’d already half-forgotten what it actually was, and why it was important. Lincoln almost remembered, eventually. Modern people, who want liberation but don’t understand the difference between liberty and license, have entirely forgotten. They want the power from the wall socket—the “rights”—without understanding where those rights come from or what they mean or what they’re connected to. And so “rights,” “the pursuit of happiness,” become the consumerist libertarian ideas that anything that you consent to is good, that the only evil is in being coerced into an action you don’t wish to do, or prevented from doing one that you do wish to do, and that we have no way to choose between alternative ends except by performing a utilitarian calculus of pleasure. You want to spend a whole day eating Cheetos and binge-watching American Idol, and your friend wants to spend that day planting a garden or volunteering a a homeless shelter? Fine—different strokes for different folks.

With our modern amnesia about what the pursuit of happiness means, we have no way to say that one is better than the other, because we have no understanding that human beings are made for a purpose, we are creatures with a natural perfection, an end, a telos, and that telos is loving each other and God, and living fruitfully as bearers of His image.

And that about wraps up my own rant. 🙂 I want to help you in your project—but if I did help it would be by reminding people of the tradition behind the eighteenth century founding tradition that you love; it’d be by reminding people of what Jefferson had already half-forgotten.

I love you, I love you! And I very much want to know what you think about all of this! And also I have to give the caveat that I haven’t read nearly as much of the primary source stuff—Aristotle and Aquinas and Augustine and so forth—as I should have. I always feel like a beginner in understanding all this. But I guess that’s not so bad.

Also you should read G.K. Chesterton. You’d love him. Try The Everlasting Man first.

Susannah

——–

Susannah Black received her BA from Amherst College and her MA from Boston University. Her work has been published in First Things, The Distributist Review, Front Porch Republic, Ethika Politika, and elsewhere; she is a founding editor of Solidarity Hall. She blogs at radiofreethulcandra.

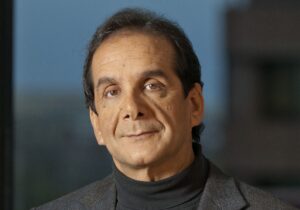

Richard Dreyfuss was born in Brooklyn, NY in 1947 and began his acting career at the Los Angeles Jewish Community Center when he was eight years old. He began doing features in roles of size in the early 1970s in films such as American Graffiti, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz and Jaws. He won the Oscar in 1978 for his performance in The Goodbye Girl. He has been acting in American theatre, television and film for over 45 years. In his personal life, Dreyfuss has undertaken a nation-wide enterprise to encourage, revive, and enhance the teaching of civics in American schools. He has become a spokesperson on the issue of media informing policy, legislation, and public opinion, speaking and writing to promote privacy rights, freedom of speech, democracy, and individual accountability.

—–

Image: Elihu Vedder, Anarchy, Thomas Jefferson Building, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA.