Leaders sometimes face tests demanding moral courage, namely the ability to do the right thing even on one’s own responsibility. Such moments test a leader’s character, and the decisions often reverberate long after they are made. A superb example of this is the Hungnam evacuation in December 1950.

After the landings at Inchon in September, General Douglas MacArthur’s UN forces pushed into North Korea despite warnings of Chinese intervention. As MacArthur’s forces neared the Yalu River, separating China and Korea, on November 24, the first Chinese counteroffensive opened. In northwestern Korea, the U.S. Eighth Army reeled southward. In northeastern Korea, the U.S. X Corps and South Korean (ROK) I Corps fell back under severe pressure. The U.S. 1st Marine Division and attached units fought an epic breakout from the Chosin Reservoir area over 60 miles of mountainous roads through some of the coldest temperatures ever encountered by the U.S. military. By December 11, 1950, the two corps were beginning to concentrate at the port of Hungnam. All troops at Hungnam were placed under the command of Major General Edward Almond, the X Corps commander.

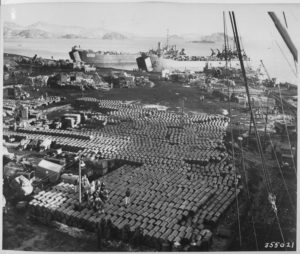

Chinese troops had cut off a land route southward, so only one option remained: evacuation by sea. It was the American Dunkirk—but unlike the British Expeditionary Force in 1940, which was forced to leave its equipment in France, Almond was determined to take all his equipment and vehicles. Hastily, 102 ships assembled from across the Far East. They began arriving at Hungnam on December 12, and over 192 trips transported 105,000 U.S., British, and ROK personnel to Pusan on Korea’s southeastern tip. The ships also lifted 18,422 vehicles, 8,635 tons of ammunition, 1,617,000 gallons of gasoline, 1,850 tons of food, and 330,000 tons of equipment and cargo. On December 24, the last troops departed, blowing up the port as they left.

There was one unforeseen factor in the evacuation: thousands of Korean men, women, and children packed everything they could carry and flooded the harbor, hoping to escape the Communists. Local officials who had aided the Americans also clamored to get out. General Almond’s orders said nothing about what to do, and he would have been justified to leave them all behind. It was a moral question only he could decide.

Almond felt a need to save these people, and committed all extra shipping space to transporting refugees. Thousands packed into transports, as many as 14,000 in one merchant ship. By Christmas Eve, 98,100 Koreans escaped from Hungnam. Five children were born at sea on the way to Pusan.

The South Koreans have never forgotten Almond’s decision to not abandon these people to the Communists. It remains a touchstone in that country, and a potent indicator of how the United States will never abandon the Republic of Korea. The 2014 Korean film Ode to My Father featured the Hungnam evacuation as a key plot point.

Hungnam’s legacy is best exemplified by a husband and wife named Moon, who were among the refugees saved by Almond’s decision. In 1952 they had a son named Jae-in, who 65 years later in May 2017 was elected President of the Republic of Korea.

In the last week of June 2017, barely a month into his term, Moon Jae-in came to the United States on a state visit. His first stop, before even the White House, was at the U.S. Marine Corps Museum in Quantico, where he laid a wreath at a monument honoring the Marines of Chosin and Hungnam. Among his remarks, Moon noted that he was here because of U.S. troops, and that he was “moved by the U.S. military’s love for humanity.” Moon also stated that “Korea remembers” what the United States did for her people during the Korean War. “That is why,” he concluded, “I do not doubt the future of our alliance.”

Although more than 65 years have passed since Hungnam, General Almond’s decision continues to have an impact.

—

Christopher L. Kolakowski works as a historian in Norfolk, Virginia. He is the author of four books on the American Civil War and World War II, including Last Stand on Bataan, and is working on a study of the 1944 India-Burma campaigns. The views contained herein are his own.

Photo Credit: Hungnam Retreat Memorial in Geoje, South Korea. By Asfreeas, via Wikimedia Commons.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024