“I was a nationalist, and not a patriot,” Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf. Despite this declaration, and all the other historical baggage that accompanies the word, there seems to be something of a movement to revive the “virtue of nationalism” today, both in America and—with Brexit the apparent battle flag—the rest of the world. This is a mistake.

Nationalism was the most powerful creature of the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, it drove the breakup of empires—Ottoman, Austrian, American, French, British, and Soviet—and contributed to the two most horrible wars in modern history. When Sir Fairfax Cartwright wrote from Vienna at the end of January 1913 that “Servia will some day set Europe by the ears and bring about a universal war on the Continent,” he was right. Driving Serbia was a nationalist quest for independence, greatness, and power. Modern defenders of nationalism would have us believe that nation-state-ism is the opposite pole to imperialism. The way Serbia treated Albanians in the two Balkan Wars that preceded the Third—The First World War—shows that this is not, in fact, true. Scholars may have the prerogative of defining words in whatever manner they choose. But we must recognize how convenient it is to shoehorn nationalism into the corner of pluralism, for it ignores swaths of global history that, properly considered, should make our stomachs churn.

Nationalism, historically conceptualized, focuses on joining the ethnos (the nation) to the demos (the citizenry, and in democratic countries, the electorate). An ethnos is simply what Benedict Anderson called an “imaged community.” Nations can be defined in as many ways as you can imagine, though ethnicity and religion are of course common ways to characterize an ethnos. The nationalist instinct may be something of a natural instinct of modernity, and few would deny that Indians should be ruled not by the British but by…Indians!

The trouble is what to do with those who do not fit into your imagined nation. Historically, a common answer has been to drive such people away (ethnic cleansing) or eliminate them entirely (genocide). This is clearly a bold claim. Those who would like detailed evidence should consult The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing (Cambridge University Press, 2004) by the distinguished sociologist Michael Mann as well as The Dark Side of Nation-States: Ethnic Cleansing in Modern Europe (New York, Berghahn, 2014) by Philipp Ther, the Chair of Central European History at the University of Vienna. In short, nationalism has a problem with diversity: on the spectrum of “the one and the many,” it insists on the “one” and seeks to dispatch the “many.” Nationalism, hence, is hardly the sort of pluralistic, Protestant, Enlightenment-ism that is being peddled today.

John Lukacs, the prolific Catholic historian, would know. Born in Budapest, he saw firsthand the power and horror of nationalism, which had pushed asunder the multi-ethnic, indeed, multi-national, ideals of the Austro-Hungarian Empire during the World Wars, after the second of which he escaped to the US. He defined the concept by contrasting it with patriotism: “Patriotism is defense; nationalism is aggressive. Patriotism is the love of a particular land, with its particular traditions; nationalism is the love of something less tangible, of the myth of a ‘people,’ justifying many things, a political and ideological substitute for religion.” Now, if we want to revive certain pluralistic and enlightened ideals and call them “nationalism,” that is one thing. But if we want to redefine the concept and ignore how the -ism has functioned historically—as a secular, not a Christian, religion—that is quite another.

It is worth taking a minute to reflect on how nationalism has functioned in American history, an exercise that nicely illustrates the other conceptual possibilities. It is not the case that nation-state-ism is the golden mean between empire/globalism on the one hand and anarchy/tribalism on the other. The American states came together at the end of the eighteenth century, as David Hendrickson has shown in Peace Pact: The Lost World of the American Founding (University Press of Kansas, 2003) not as a nation-state, but in a federal union. Nation-states, in contrast, are typically formed through war, and indeed, out of the ashes of the American Civil War, a new nation was birthed. The Spanish-American War in 1898 was the way this new nation came of age, casting aside its old divisions, accomplishing the “transformation of America” from “a confederacy…into a nation,” an obscure Princeton professor named Woodrow Wilson declared in 1901. Notice what happened in this war of nationalism (and of choice): America acquired an empire (the Philippines, Hawaii, Cuba, and Puerto Rico).

As Murray Forsyth argued in his 1981 book Unions of States, historically (and conceptually) both federal unions and empires have permitted the one and the many to coexist. By the time of the Reformation, the Swiss Confederation, which had begun in the Middle Ages, was split between Catholic and Protestant cantons. The Confederation’s structure, Murray summarizes, saved “Switzerland from the drastic and ferocious struggles that devastated the Germanic Empire.” Likewise, as intimated above, the Holy Roman Empire (Austria-Hungary’s predecessor) accommodated tremendous diversity in its thousand-year history, never demanding “the absolute, exclusive loyalty expected by later nationalists,” as Peter H. Wilson argues in Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire (Harvard University Press, 2016). The point is not that these historical examples should be reproduced today, something obviously inappropriate given the realities of this present age. It is rather that we need not be beholden to the nationalist (i.e., nation-state-ist) conception of the polity. There are great reservoirs of wisdom that we can explore from the past.

In an age in which nationalism remains a potent force, doing so is critical. Today, nationalism is the driving force behind the persecution of Uighurs in China and the ethnic cleansing committed against Rohingya in Myanmar. In both cases, the objective is to seek a homogenous ethnos. In both cases, the elements of Lukacs’ conception of nationalism are present: aggression, myths of a “people,” secularized religion.

These cases may feel “other” to us: we, after all, have already had our wars of ethnic cleansing (against Native Americans) and nationhood (the Civil and Spanish American Wars)—and this is of course true. But increasingly, it is becoming undeniable that the fundamental problematic, the “principal contradiction,” in American life is, How can people with first-order moral and philosophical disagreements figure out how to coexist at an individual level and promote human flourishing at a societal level? Nationalism and nation-state-ism have no answer to this question.

—

Jared Morgan McKinney is a PhD candidate at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University (Singapore). He holds master’s degrees from the London School of Economics (Department of International History), Peking University (School of International Studies), and Missouri State University (Department of Defense and Strategic Studies). His scholarly essays have appeared in the Journal of Strategic Studies, Third World Quarterly, and Asian Security.

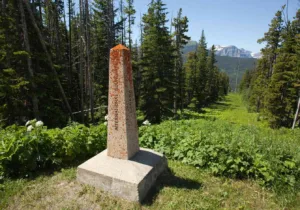

Photo Credit: Srebrenica Genocide Memorial. By Jelle Visser, via Flickr.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024