Protestantism, and particularly evangelical Protestantism, has made great inroads throughout Latin America over the course of the past few decades, in what had previously been an almost wholly Roman Catholic Latin America (which contains nearly 40 percent of the world’s Roman Catholics), a legacy of Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule that has had deep political and cultural impact in the region over the centuries. In most of Latin America, Protestants are becoming either a sizable minority or in some cases, particularly in parts of Central America, are now approaching parity with Catholic numbers. This rapid growth of evangelical Protestantism is impacting the region in profound ways, reshaping culture, society, domestic politics, and the international relations of the region.

The first permanent, native Protestant church in Venezuela was established in 1900 by the American Presbyterian missionary Dr. Theodore Pond and called El Redentor (The Redeemer). The growth of Protestantism was slow but steady over the next several decades. The late 1960s saw the beginnings of a much quicker growth of evangelicalism, and data covering the period 1967–80 shows that the evangelical community in Venezuela grew exponentially during just those 13 years, from 47,000 to 500,000, with Pentecostal churches representing the largest proportion of that growth. Since 1980, the growth of evangelicalism was said to have put the evangelical proportion of Venezuela’s population as of 2014 (as per a Pew study) at 17 percent of the total, or more than five million. Evangelical leaders estimate that the proportion of the population that is now evangelical is approximately 20 percent, an estimate in keeping with Pew’s forecasts for its growth through the region as a whole. Approximately half of Protestants in Latin America belong to Pentecostal churches, giving Pentecostalism a far greater influence among Protestants in Latin America than in the United States.

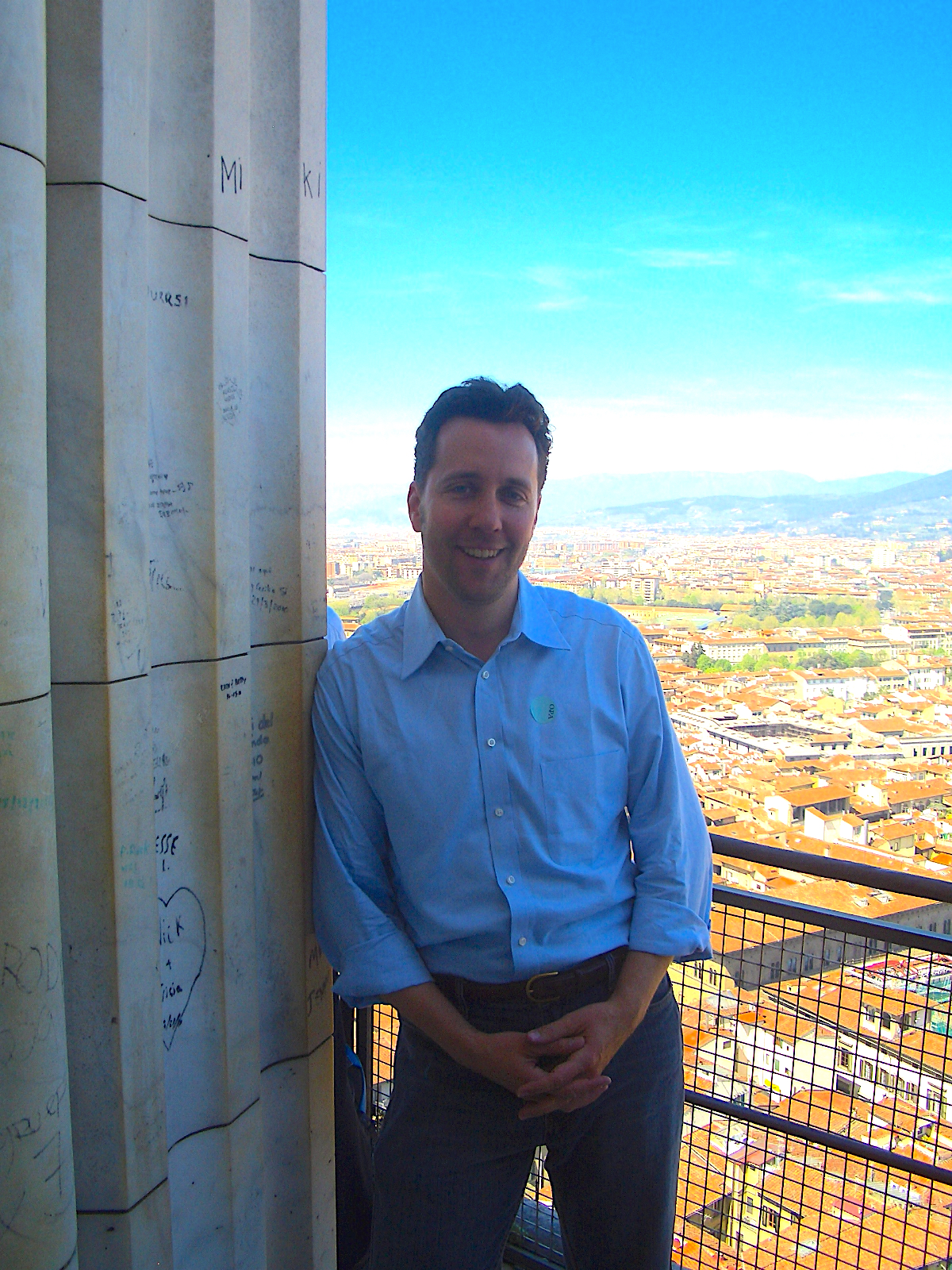

Samuel Olson is one of Venezuela’s most well respected evangelical leaders, and is a respected leader not just in Venezuela and Latin America, but globally. Born in 1942 to American parents of Scandinavian heritage (in case any of you are wondering why his surname is perhaps less Latino than one might expect of a Latin American faith leader) who had come to Venezuela in 1940 as evangelical missionaries, Olson received most of his education in the United States, including an undergraduate degree at Johns Hopkins University, an MA at Middlebury College, and an MDiv at Princeton Theological Seminary. He has been the senior pastor of a large evangelical megachurch in Caracas, Iglesia Evangélica Pentecostal Las Acacias, since the 1970s. In 1984, he founded the Evangelical Seminary of Caracas (which is linked to the Reformed Church in America), of which he serves as president and where his brother, Daniel, serves as director, and is also president of the Evangelical Council of Venezuela. Reverend Olson has also been active for several decades in the World Evangelical Alliance, including serving on their International Council, and founded the Ibero-American Forum for Evangelical Dialogue, now known as the Latin American Evangelical Alliance.

Olson has also been an extremely energetic and active civic leader, founding and leading over the past several decades numerous civic organizations that seek to address major societal needs in both Venezuela and across Latin America. Just a few of these include the Feed the Starving Children Foundation, the Armando Diaz Gonzalez Foundation, which focuses on slum restoration, Hogar Nueva Vida, a drug rehabilitation center, an organization that seeks to help Venezuelans begin microenterprises, etc., etc. He has also served on the board with Rabbi Pynchas Brener of Conciencia Activa (Active Conscience) and is vice president of the Committee on Relations Between Churches and Synagogues in Venezuela.

Paul Coyer: Reverend Olson, Protestantism, and particularly evangelical Protestantism, has made strong inroads in Latin America in the past few decades. Can you describe for us the growth of evangelicalism in Venezuela in which you have played such a large role, and perhaps also a bit about the various theological divisions and how they have manifested themselves in how the church has lived out its calling in public life?

Samuel Olson: European Protestantism arrived in our country first in the form of Anglicans and German Lutherans in the colonial era in the eighteenth century, remaining a tiny minority in a sea of Roman Catholicism. Both European and American Protestant denominations began sending missionaries to Venezuela in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, so a broad range of theological perspectives, including differing perspectives on the proper relationship of the Christian believer to the state and society, began to make themselves felt in the country. Western missionaries tended to teach Venezuelans to remain aloof from politics and to focus on preaching the Gospel and ministering to the poor, showing a social consciousness but still seeing the preaching of the Gospel as the primary way to transform lives and society more broadly. The influx of American missionaries prominently included Baptists, Pentecostals, the Evangelical Free Church, and the Lutherans (Missouri Synod).

Presbyterians and Reformed/Calvinists also had an evangelistic focus early on while at the same time being active in founding clinics and schools, but gradually lessened their emphasis on evangelism and allowed social activism to become the dominant expression of their faith. Baptists, Pentecostals, and the Evangelical Free Church began to arrive in some numbers in Caracas in the 1940s, with a very different perspective on the role of the church in society than the Presbyterians and Reformed churches did, focusing their ministry on evangelism. A strong bifurcation became increasingly pronounced between those who privileged social and political action and those who privileged preaching the Gospel.

My own parents arrived in Venezuela as missionaries in 1940, and the broad range of theological and ideological divisions among evangelicals and mainline Protestants were in full display at that time. Some evangelicals opposed the dictatorships of the 1930s, 1940s, and much of the 1950s by proposing a democratic vision for the country as an alternative. Others held a more radical vision of the nation with strong Marxist leanings and saw in the elites the causes of the common person’s poverty and subjugation. This division within Venezuelan evangelicalism can be seen today, with the Left-leaning mindset being manifested institutionally in the Evangelical Pentecostal Union and in Movimiento Cristiano Evangélico de Venezuela led by Moisés García. Most evangelical churches for much of the twentieth century, however, perceived social and political activism as being the work of the political Left, and eschewed it, rejecting a major role for the church in this area.

All of these people knew each other and accepted their ideological differences. You might say that there was an accepted coexistence in which these diverse actors played the role of loyal opposition to the military dictatorships that dominated Venezuelan politics until 1958.

Paul Coyer: That orientation and mindset changed among Latin American evangelicals, though, hasn’t it? Can you trace that change for us and describe how it has impacted Venezuelan politics and public life?

Samuel Olson: This orientation on the part of Venezuela’s evangelicals didn’t change much until the late 1960s. This way of seeing Christianity, the privileging of preaching, teaching, and evangelism, to the exclusion of a more active social and political witness, limited the church’s influence in society, and in particular separated it from having any real influence among the most influential social classes of Latin America, the educated, the wealthy, and the social elite. This is one of the most important ways that it limited evangelicalism’s impact on public life as these social strata ruled the nation.

However, in the early 1960s the government signed the Modus Vivendi with the Roman Catholic Church, which motivated many evangelicals, feeling distinctly left out, to become more active in public life. This led to the formation in the late 1960s of an organization that became the Evangelical Council of Venezuela with my involvement in the 1970s, the purpose of which was to give evangelicals a greater voice in the life of the nation and a greater public witness. From then through the 1990s, increasing numbers of evangelicals began to search for their calling through social and political action, becoming involved in such political parties as Acción Democrática, COPEI (Partido Socialcristiano), URD (Unión Republicana Democrática), MEP (Movimiento Electoral del Pueblo), and others. Due to this increased motivation to make their voice heard in the public square, many evangelicals came to occupy significant positions as senators, deputies, social communicators, party secretaries, ambassadors, educators, jurists, etc.

Paul Coyer: Hugo Chávez came on the scene in the late 1990s as evangelicalism’s impact was beginning to be felt more in social and political life. Chávez actively worked to cultivate support among evangelicals and brought them into his government and raised them to various other prominent roles, correct? And this is also in the context of a series of previous governments ruled by Acción Democrática or COPEI which expressed no real interest in the religious life of the nation or its evangelical community. Can you help us to understand evangelical attitudes toward Chavismo, which have been perhaps more complex than many would realize?

Samuel Olson: Evangelical attitudes toward Chavismo have, indeed, been complex, you are correct. I’ve described the branch within Venezuelan evangelicalism that tended toward more Left-leaning views on social activism, and that aspect of evangelicalism found that Chávez’s campaign rhetoric in 1998 that claimed concern for the poor and the marginalized resonated with them. He was perceived by many to be struggling for the poor and against the ingrained and endemic corruption that was undermining the cohesion of society. Understanding this context in which he rose to power is critical to understanding why so many evangelicals would have supported him.

Compared to the case at present, Venezuela was a much more democratic and prosperous country in the 1990s, but after 40 years of what in hindsight now appears to have been a successful and wealthy democracy, particularly by Latin American standards, many people had nevertheless become disillusioned with a corrupt series of governments perceived to have been unresponsive to the poor and marginalized and much else besides. A system which had seen primarily two parties, Acción Democrática and COPEI, dominate Venezuelan politics since the restoration of democracy in 1958 had lost legitimacy, leaving the door open to a new presence. This was particularly after the forced departure of President Carlos Andrés Pérez in May 1993. Everyone knew that corruption was the order of the day and that there was a deep struggle for control of the state. His demise simply undid the threads of the system. The system slowly fell apart and the country was ready for a new day.

Hugo Chávez successfully played upon the popular sense of disillusionment to win support from the common people, promising to tackle corruption, to care for the poor and marginalized, etc. So one must remember that at that time much of the Venezuelan population in general did support Chávez because he said things they had been longing to hear. He convinced a large part of both the general population and of evangelicals, with the exception of those who already knew the true nature of such political movements because of what had happened in other nations, prominently Cuba, after such a “revolution.” His message brought many evangelicals more strongly into public life, and Chávez rewarded those evangelicals who supported him by bringing them into government offices and placing them into positions of recognition. As events progressed, and as the country has worsened, those who accepted Chavez’s blandishments have now been compromised and are unable to hold principled ethical positions vis-à-vis the regime.

Paul Coyer: Although a significant portion of evangelicals supported Chávez and some remain die-hard Chavistas, the relationship between Chavismo/Venezuelan socialism and evangelicalism has been increasingly strained. In 2014, the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV) in a government “ideology workshop” rewrote the Lord’s Prayer, redirecting it to the departed Hugo Chávez, beginning “Our Chávez who art in heaven, the earth, the sea, and we delegates,” and asking an apparently deified Chávez to “protect us from the temptation of capitalism.” A known evangelical leader called it “sacrilegious, an act of idolatry and desecration, and a trivialization of the sacred.” Another point of conflict took place when Chávez broke diplomatic relations with Israel. Can you describe how Venezuela’s evangelical community has attempted to live out its calling in Venezuelan society in such circumstances and how it has handled relations with the PSUV?

Samuel Olson: Well, as I’ve mentioned, the evangelical community in Venezuela has always been characterized by a multiplicity of views toward the proper role of the Christian in Venezuelan society and public life, and those different perspectives have manifested themselves in differing perspectives toward Chavismo. Despite the fact that the vast majority of Venezuelans have turned against Nicolás Maduro, some continue to support Chavismo as an ideology, including among evangelicals. I am suggesting that in such a situation as we now face, evangelicals are going through a difficult time of having to sift out their convictions and values. Individuals will have to come to grips with this reality, making very personal and corporate decisions.

A few years ago I held a series of conversations with Cuban evangelical leaders who helped me to better understand their situation and it also shed light on our own. They explained that the Cuban church had limited options under the Castros. Those who stood vocally against the government would be taken to trial and end up in prison—or at a minimum politically and socially isolated; they could oppose the regime in a low profile, in a more covert manner which would be minimally effective but allow them to continue their ministries even though they would be monitored; or they could support the Castro regime’s ideology in the hopes that they could then minister freely. Those who did compromise in this manner have ended up being a source of permits and visas for other evangelicals who would have had a more difficult time obtaining them if they had not had these avenues. So being faced with such choices as an evangelical believer is a bit more complex than outside observers may immediately appreciate. Over the past decades, Cuban churches have had to sift through their values and convictions, deciding how to remain true to the Gospel. This is the reality that the Venezuelan church now confronts as the nation works to resolve the profound issues it faces. The stand we now take is defining the spiritual and moral fabric of the nation

Paul Coyer: Can you describe some of the struggles that churches have had to deal with during these years, and how you have done so in particular?

Samuel Olson: Over the years the evangelicals have taken a stand on certain issues and have thus faced possible consequences, such as the loss of their church property. One church was invaded during its Sunday morning service and was to be taken over. The believers stayed in their church building. Meanwhile, other believers from the church drove over and surrounded the property, and those who had entered to take the property were openly confronted and opposed. Meanwhile, the television channel was called in, and the confrontation became public news. When this occurred, the invaders were forced to back down, and the church kept its building.

On another occasion, the church of which I am the senior minister was advised that people in our neighborhood had decided to take over the building using their political connections. At the time, we were just finishing 40 days of fasting and prayer. Upon knowing about this, the fasting and the prayers were extended another ten days, which gave us more time to reach out to those on every level who could help. We knew that the threat was to be taken seriously. Through our behind-the-scenes activism and pushback, we were eventually told that it had all been a mere misunderstanding and was only a “rumor.” This communication was given to us after we had demonstrated with documents that we were involved in a myriad of social and educational programs, that the evangelicals of the nation were mobilizing for a more unified response to the threat, and that the message was being spread on social media.

Paul Coyer: Another example of tension between the Chavez government and Venezuelan evangelicals occurred in 2005 when Chavez ordered the New Tribes Mission (NTM), a missionary organization that had for several decades worked among various indigenous tribes, out of the country, asserting that the government was securing national sovereignty and alleging that foreign elements had been working with malign intentions and some of the evangelicals were working with the CIA. Can you explain a bit more about this?

Samuel Olson: New Tribes Mission had worked among the natives since the 1940s with governmental approval. Multiple generations of missionaries rooted their lives among the indigenous tribes to whom they ministered, setting up medical clinics and schools, creating writing systems for the various tribes that had had no such system to that point, recording their grammar, teaching the history of Venezuela, and providing translations into their mother tongues of the scriptures. In this way they helped to preserve their languages and cultures from potentially disappearing. They discipled those who converted, and these believers then established native Christian communities.

In 2005, Chavez ordered the NTM to leave the territory where they had worked and served for over 60 years and buried loved ones during that period who had given their lives for the cause of Jesus Christ. The rationale given was that we were violating Venezuela’s national sovereignty, and some of us were accused, as you mention, of working with the CIA. It was a very frustrating experience and served as a wakeup call to some evangelicals that Chavismo wasn’t all that they had assumed it to be.

Paul Coyer: You took a strong stand recently when on February 1 you made a public statement highly critical of the Maduro regime in the wake of the starvation, unchecked crime and violence, endemic corruption, etc. While you prefaced your remarks by saying that “evangelical people are not political belligerents/combatants—they are for separation of church and state,” you nevertheless criticized the regime on the grounds of the lack of social justice under the regime, explaining that the Christian is called “to live in righteousness with God” and that this sentence has both spiritual and social implications. Can you explain a bit about what you mean when you use the phrase “living in righteousness with God”?

Samuel Olson: Christians do believe in social justice, but much depends upon the definition of that term. It has come to mean something very different under Chavismo. I believe in the centrality of preaching the Gospel and of evangelism, but also strongly believe that the church does have a large role to play in ministering to the needs of the most vulnerable of our society. I define “living in righteousness with God” in both theological and social terms. As James wrote, “faith without works is dead”—you need both. I do not see the church’s role as primarily being one of social and political activism, however. There is a balance that must be sought for a church to live out its calling to society in a prudent and effective manner.

Paul Coyer: You have prized working across confessional boundaries and have been heavily involved in organizations that facilitate interfaith communication and cooperation, through which you have come to know other faith leaders such as Rabbi Pynchas Brener and Cardinal Baltazar Porras. Can you talk a bit about that?

Samuel Olson: Yes. As you discussed in your article on Venezuela’s Jewish community and Chief Rabbi Brener, in the 1970s an interfaith organization called the Committee of Relations between Churches and Synagogues in Venezuela began, and I was invited to become part of the organization’s leadership together with Rabbi Brener and Archbishop Rodriguez of the Roman Catholic Church. This organization has been extremely useful in strengthening relationships among the various faith communities of Venezuela by building bonds of trust and close communication between its various leaders, and is a big reason that I have developed and continue to maintain close relations with Venezuela’s Jewish and Roman Catholic leaders.

Paul Coyer: Venezuela is facing some of the darkest days in its history. Your own congregation has dropped by about a third due to migration out of Venezuela due to the desperate conditions. I know you’ll agree that faith leaders and communities will need to play a large role if the nation is to be rebuilt and Venezuelan society healed. Despite all of the challenges, Venezuela’s evangelicals are dedicated to doing what is necessary to rebuild the country. Can you describe how they can do so?

Samuel Olson: We are heartbroken at the current state of our nation and desperately want to contribute to its rebuilding. Of course, the extent to which we are able to contribute and the timeline in which we can begin to seriously do so depends to a large degree upon the resolution of the political crisis we now face. We are ministering to our broken society to the degree we can at present, but much more could be done. Faith communities are uniquely suited to rebuilding shattered societies due to their commitment to those societies, their knowledge of their local communities, and their reach, and Venezuela’s evangelical community is fully committed to doing whatever is necessary to rebuild our country.

Photo Credit: Samuel Olson preaching on November 26, 2017, at La Iglesia Evangélica Pentecostal las Acacias. Screenshot of video, via YouTube.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024