On the sunny afternoon of May 10, 1900, a crowd gathered at Pier 1 in Brooklyn, New York, to offer prayers and blessings for the maiden voyage of the US Navy steamship Quito. Laden with 5,000 tons of corn and seeds, the Quito was bound for famine-stricken Bombay. The cargo, as the ship’s sponsors proclaimed, represented “not only the life-saving gift of food to the starving multitudes of India, but also a tender message of love and sympathy from God’s children on this side of the globe to those on the other.” As the vessel got underway, the supporters sang “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” and listened to letters from President William McKinley, Secretary of State John Hay, and New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt, who each expressed regret for their absence and praise for the “splendid work of American benevolence.” Attention then turned to the Reverend R. G. Hobbs’ benediction:

This ship goes out of the harbor to a far-off land in the name of that God who made of one blood all the nations of the world: in the name of that Christ who died, that all men might be drawn in into the bonds of a common brotherhood.

The Quito’s departure, as well as its celebrated arrival in Bombay harbor in late June, was sponsored by The Christian Herald, the most influential religious newspaper in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century. Purchased by the evangelical philanthropist Louis Klopsch in 1890, the New York-based weekly periodical had reached “a pinnacle of popularity as an organ of widespread humanitarianism by the time of the devasting India famine of 1900.”

Throughout the preceding decade, the enterprising Klopsch, along with his editorial partner, the charismatic Brooklyn preacher Thomas de Witt Talmage, strove to make The Christian Herald “a medium of American bounty to the needy throughout the world.”

They were fantastically successful. As pioneers of pictorial-journalism, Klopsch and Talmage took advantage of new photographic technologies to publicize humanitarian crises at home and around the globe. By deftly combining images and narratives about human suffering with biblical exhortations for almsgiving and to deep-seated expectations about the United States’ role as a redeemer nation, these moral entrepreneurs induced readers to “open their hearts, hands, purses, and granaries to feed the hungry, send or carry aid to the sick, and to spread the gospel message everywhere.” When the Quito sailed, it bore the largest cargo ever carried by any vessel bound on an errand of mercy.

Such stories provide ample reflection points in Tufts University professor of religion Heather Curtis’ Holy Humanitarians: American Evangelicalism and Global Aid. Deeply researched and cogently argued, the book reveals the crucial role evangelicals played in the development of international humanitarianism at a time when the United States was extending its global power through economic expansion, military imperialism, and missionary outreach. In Curtis’ hands, The Christian Herald takes center stage not only as an expression of the missionary impulse of Klopsch and Talmage, but as a means for shaping and harnessing that impulse in their readers. The impulse was insatiable.

Throughout its publication life, The Christian Herald championed everything from soup kitchens, to schools, to relief for victims of famine, war, political violence, economic downturn, earthquakes, and floods all across the world. By the time Klopsch died in 1910, he was heralded as “one of the historic figures in the annals of civilization, a friend of all humanity whose genius in the organization of benevolences made him a blessing to all mankind.” Called by leaders of the world the almoner of nations in distress, Klopsch was awarded highest civilian honors from numerous foreign heads of states from Germany to Japan. During his lifetime, the subscribers to The Christian Herald donated over $3.3 million to Klopsch’s vision—an amount equivalent to approximately $83 million today. No other humanitarian effort came close to mirroring its output. Only the American Red Cross, which was subsidized by congressional appropriations, came even close to keeping pace.

But despite such extraordinary accomplishments, Klopsch and The Christian Herald remain essentially unknown today. Few historians have recognized the newspaper as a major force in shaping “the humanitarian sentiments and habits of the American public during a time of increasing globalization.” Aiming, in part, at this remedial task, Holy Humanitarians tells this forgotten story and shows how an entrepreneurial evangelical preacher and an ambitious charismatic preacher “deployed religious media to foster a tremendously popular movement of faith-based aid” that, Curtis avers, continues to have “an enduring influence on how Americans regard and respond to suffering at home and abroad.” In this sense, Curtis offers us something of a religious autobiography of American charity.

She begins by exploring how and why Klopsch and Talmage strove to make The Christian Herald “an instrument for the betterment of humanity.” From the twenty-first-century perspective, it might seem surprising to some that a newspaper could ever obtain such success as a tool of humanitarian agency. But newspapers of the time served as essential vehicles in establishing and animating communities around shared ideas—in The Christian Herald’s case, broad evangelical sentiment. This sentiment catalyzed The Christian Herald’s ambition to accomplish good works through becoming the preeminent channel for extending American charity around the globe both by steering public opinion and also by motivating its constituents to participate in “great political and social and moral enterprises” such as “breaking off a million chains, standing for liberty against all oppression, and fostering an all-embracing sympathy for suffering people.”

Such efforts inevitably courted controversies not unfamiliar today. For instance, during the Cuban War of Independence in the late 1800s, Talmage editorializes that American military intervention could be a form of humanitarian intervention. The reality of American power, he asserts, made the US “the equal amongst the greatest” of nations. Merging this with the US “long-standing commitment to the ideals of freedom, democracy, and Christian morality,” Talmage suggests, meant that the United States was “uniquely positioned to influence global events by pursuing a foreign policy based on the Golden Rule.”

Talmage, Curtis notes, recognizes possible theological tensions. But he sees no inconsistency in asserting that “Christianity is a religion of peace,” even as also he also insists that American intervention in Cuba was not an act of aggression but, rather, a “fight forced upon us by considerations of humanity.” In light of this, Talmage gestures to Paul’s letter to the Roman church and asserts “God has put into our hands a sword” to “vindicate and deliver those that have been oppressed.”

In Cuba and similar cases, therefore, The Christian Herald avers that like the Good Samaritan the United States was coming to the aid of a suffering stranger. All in all, this had the effect of transforming the theological ethics of American Christians. Curtis writes that “as the United States continued to extend its economic, military, and political power around the world, the concept of imperial humanitarianism replaced pacifism as the dominant framework through which American evangelicals came to envision the nation’s global mission.”

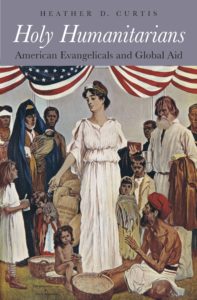

This push for benevolent American intervention sometimes risks devolving into ugly forms of American exceptionalism. Curtis recognizes this risk and points to Holy Humanitarians’ jacket illustration. Taken from the cover of a June 1901 Christian Herald, “America, Almoner of the World” depicts Columbia, the personification of America, standing amongst the world’s poor and needy. In one hand she holds what appears to be a Bible. The other hand, open, is flowing with grain. It’s not immediately clear where the grain is coming from, but there’s the hint of a suggestion of blood and stigmata. In one sense the image is appropriately straightforward: there are those who need grain and those who have it and can share it. In other ways, Curtis asserts, the image is more complicated. Among other concerns, such an image—as do many of the images The Christian Herald employed—risks blurring the distinction between empathy and pity.

Pity, Curtis worries, reinforces civilizational hierarchies between the “haves” and “have nots” or fosters the giving of charity not as a by-product of love as much as of repugnance. The Christian Herald became expert at “spectacle and drama” and utilized “gripping headlines, stirring stories, and attention-grabbing images” as indispensable tools for publicizing distressing situations and exposing wrongs that needed to be righted. But, while effective, such emotional appeals can be dangerous. Emotions can be epistemologically significant—they can help us know the truth about things. But they can also be misleading. Such “famine photography,” as Curtis coins it, can short-circuit more reasoned, nuanced responses. We know this from our own day, in which such “iconography of suffering” is used to promote everything from open borders, to animal welfare, to pro-life causes. Images can be rightly used to promote just causes, of course. But Curtis is right to note the need for caution.

Over the course of its publication career, The Christian Herald wrestled with other familiar tensions. When and under what circumstances should America risk its own well-being for the sake of other nations? Do American Christians have any special obligation to fellow Christians throughout the world that trumps our obligation to the needy of other faiths? What is the relationship between evangelism and relief work and humanitarian rescue? How do you promote almsgiving as not only the responsibility of a privileged few but a practice incumbent on all Christians no matter how humble?

One of Holy Humanitarians’ most helpful contributions is helping us explore these questions. Another is the reminder of all that grassroots endeavors can accomplish in alleviating human suffering, even outside the domain of governments and other bureaucracies. Curtis reminds us of how evangelicals and others can punch well-above their weight with humble efforts.

She also reminds us of the crucial role the missionary impulse has played in fueling and helping to shape the character of American engagement in the broader world. According to the World Giving Index, America continues to be the most generous nation in the world with the highest rate of charitable contributions as a percentage of gross domestic product. Through monetary gifts and humanitarian efforts, Americans, between Klopsch’s day and our own, have saved millions of victims from starvation, war, natural disaster, and poverty.

For Klopsch, Talmage, and The Christian Herald, faith was behind everything they did. The connection between Klopsch’s love of God and his love for his neighbors was manifest in his practical work. As the journalist Irving Bacheller noted of Klopsch:

[He] preached with bread; he prayed with human kindness; he blessed with wheat and corn. His best missionaries were loaded ships; his happiness was in mitigated pain. His week-day was as holy as his sabbath, his office as consecrated as his church, his note of hand as binding as his creed, his business as sacred as his religion.

While the connection between faith and humanitarian aid isn’t the only connection extant, it is a connection that should neither be lost nor taken for granted.

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!