“Is a Settlement in China Possible?” by Michael Lindsay

March 31, 1947

The first and most fundamental question is whether there is a possible basis for co-operation between the Communists and other parties, or whether there are differences in program and ideology so fundamental as to make any real co-operation impossible.

Here the answer would seem to be that there are no fundamental obstacles to co-operation between the Communists and the independent liberal parties or the left-wing Kuomintang. The Communists are certainly Marxists, but they are consistent Marxists who believe that socialism is something which can only come when China has developed into a modern industrialized society, after at least decades of development during which free enterprise must play an important part. In their present economic program the Communists would actually give a larger part to free enterprise than the official Kuomintang policies. The other factor which would make effective co-operation possible is the strong anti-authoritarian trend which can be found in a great deal of Chinese Communist policy. The Chinese Communists have always been fighting guerilla warfare in which they faced certain defeat if they lost popular support and have come to realize that identity between Communist policy and the desires of the masses [were] not something which could be taken for granted as an a priori truth, as some other Communist parties have tended to do, but was something which must be continually checked by giving real power to popular opinion.

The Chinese Communist approach to political organization has always been from the bottom—building up mass organizations, setting up elected village councils and county governments, replacing the old police and gendarmerie by the village militia (which [ensures] a real transfer of local power), and so on. Formal organization has always been loose. There has never been a central government at Yenan but only a number of local governments kept together in general policy by common Communist leadership. Even in the army, the militia and some local guerilla units have been under the local civil governments, not under Yenan headquarters.

This approach through mass organization and local popular control has been very effective. Reforms have really been carried out, government is honest and, by Chinese standards, efficient and there has been a rapid growth of political consciousness among the peasant population.

Other parties might put more emphasis on discussion at the higher levels, on the rule of law as against unrestricted majority power, and so on, but the differences are matters of emphasis rather than principle. In a coalition the Communists could make an essential contribution in the methods and personnel for real rural reconstruction, and the other parties in the technicians and administrators more necessary in the cities and at the higher levels of government. In practice the Communists have been able to co-operate with the Democratic League and left-wing Kuomintang members.

On the other hand there is a fundamental conflict of principle with the right-wing Kuomintang attached to Confucian traditions. The Communists represent the tradition of peasant revolt which the old Chinese ruling class has always fought by every possible means. They also represent the introduction of the revolutionary Western tradition into the basis of Chinese society which is completely destructive of the old Chinese social structure.

On a more practical plane, both the very powerful vested interests who have made official positions the main road to wealth in China and the powerful landlord interest face loss of power and income with the spread of Communist influence.

Chiang Kai-shek’s sympathies are clearly with the right-wing. What he has taken from the West is nationalism and to some extent the idea of bureaucratic efficiency through disciplined organization and exact rules, but his speeches and writings are full of references to the basic formulae of the Confucian tradition. “China’s Destiny” condemns both liberalism and communism as incompatible with Chinese culture. He is also closely associated with the group having the strongest financial vested interests against change. As against this, he was able to rise above party affiliations to national leadership in 1937 and 1938, and, under similar pressure, might conceivably do so again.

From the Communist point of view it has always been reasonable to accept any compromise which allowed effective power to elected local governments in North China because their system is certain to spread under political competition. It would be impossible for the Kuomintang to maintain the “pao-chia” system of political control or the old social and economic structure, when peasants in adjoining areas were paying lower rents, had much more political power and got more from the government in return for much lower taxes.

Kuomintang official policy has admitted local self government, land reform and so on in principle but has qualified their rapid implementation with arguments for the necessity for administrative unity and enforcement of law. To some extent this is no doubt a genuine concern for law and order but it can also be represented as a rationalization to protect vested interests. Even under American conditions there is sometimes a conflict between the principle of due process of law and that of government action expressing the popular will. This conflict is much sharper in a society with no traditions of democratic action where the police and machinery of government are in the hands of the group with a vested interest against change. A Kuomintang leader once argued that it was more important to prevent injustice by the weak against the powerful, than by the powerful against the weak, because the latter was merely injustice while the former also subverted the social order.

The negotiations seem to show that the main obstacle to settlement has been the dominant reactionary group in the Kuomintang. Throughout the negotiations the Communists have been willing to accept a minority position in the central government, provided elected local governments were allowed to function and the provinces had sufficient powers to carry out their own social and economic experiments. They have been willing to merge their army with the Kuomintang army on comparatively unfavorable terms provided they had reasonable guarantees of safety without their own army to protect them.

Since 1938 the Kuomintang has never been willing to accept this sort of compromise. During the war they seemed to regard the Japanese as the lesser enemy. Kuomintang demands, for example in June 1944, implied the abandonment of most of the Communist areas to Japanese control, and at the end of the war about 400,000 Kuomintang troops were serving in the Japanese forces against the Communists. After V-J Day the puppet troops were incorporated in the Kuomintang army and, at the end of August, the Japanese were ordered to make a counteroffensive in North China against the Communists.

Though this gave the Communists good reasons for suspicion, the party line until last summer was one of conciliation. After the negotiations in September, 1945, Mao Tse-tung was criticized in Yenan for making actual concessions in return for Chiang Kai-shek’s promises, but obtained a vote of confidence when he argued that it was worth making very big concessions for any hope of avoiding civil war. In fact the Communists evacuated their areas south of the Yangtze River but, within a few days of the joint declaration that agreement would be sought by peaceful means, the Kuomintang launched a major offensive into Communist held areas of North China and the other Kuomintang promises were broken or evaded.

Under General Marshall’s mediation the Kuomintang, for the first time, offered concessions which made settlement possible. But when it came to the point they were very reluctant to implement them. The Kuomintang secret police were never really restrained, the agreement for quickest possible disbandment of war-lord and puppet armies was never applied, demobilization was evaded, no arrangements were made to elect provincial governments, and so on. In March, 1946, when General Marshall had returned to Washington, the concessions were largely repudiated. The Kuomintang Central Executive Committee accepted the agreements but with amendments repudiating such key points as provincial constitutions and the control of the executive by the legislature. The proposed composition of the government was altered to destroy the veto power of Communists and Democratic League combined over major changes in policy.

Local Communist units broke the truce agreement quite often, mainly against puppet troops, but the Communists made concessions on many points to reach the agreements and a considerable part of the Communist army was demobilized. The negotiations would probably have had a better chance of success if the Communists had not so blindly followed the party line of conciliation. General Marshall would have faced a much clearer situation if the Communists had forced the issue on points where Chiang Kai-shek had clearly to choose between repudiation of the reactionaries in his party and the success of the negotiations. For example if he would not or could not control his own party organizations or the local police in his own capital to prevent what General Marshall calls “quite obviously inspired mob actions,” there was no real hope of settlement. Again the Communists never forced the issue on the puppet armies though they were the main obstacle to the working of the truce agreement and their disbandment was promised both in October, 1945, and in February, 1946. To act against leading puppet generals like P’ang Ping-hsun or Wu Hua-wen, Chiang would have had to repudiate the extremist group which had encouraged their desertion to the Japanese.

It is clear that there was a change in the Communist party line during the summer. What seems to have caused it was the repudiation of the agreements by the Kuomintang in March and the failure of America to protest. This must have seemed to confirm the doctrinaire Marxist position that, whatever General Marshall’s good intentions, America was an imperialist power which could not be an honest mediator where Communists were concerned. Also it must have seemed clear that conciliation did not call forth any reciprocal evidence of good faith from Chiang Kai-shek. Where the Communists spoiled their case was by starting their offensive in Manchuria before making a formal protest to General Marshall against the repudiation of the agreements. If they had made the protest and the United States as mediator had refused to act they could have considered the agreements at an end.

Actually when General Marshall returned he found both sides breaking the agreements and never regained control of the situation. First the Kuomintang demanded further concessions and then the Communists demanded a return to the positions of the original truce agreement.

The Communists do not seem to have given up all hope of settlement but are now clearly unwilling to make concessions without some positive evidence of good faith on the other side. Of this there has been no sign. The truce on existing positions which was offered in November would have given the Kuomintang a useful period to consolidate their gains and freed troops to suppress new guerilla activities in the south. The Kuomintang could have started the war again a month or two later in a much stronger position. The new constitution is worse than the January agreements on several important points such as provincial powers and civil liberties. The Kuomintang secret police are still active.

Much has been made of the damage done by the Communists as showing their determination to fight without regard for the interests of the people but there is no evidence that the Kuomintang shows any greater concern for the population of the Communist areas. They have always blocked UNRRA supplies. Foreign correspondents have reported widespread air attacks, including attacks on railways while the Communists held them, and the Communists report general destruction of property and ill treatment of civilians by the Kuomintang armies.

The Kuomintang has never been willing to make concessions except under American pressure, even the minor concessions of January, 1945, or the new constitution. Since political competition with the Communists, or even genuine reforms without them, would mean the end of the dominant reactionary group this is quite understandable. American pressure has never been sufficient to force out the reactionaries and secure a settlement because, in General Marshall’s words, “The reactionaries in the Government have evidently counted on substantial American support regardless of their actions.” Though this has not been the intention of the American government it has been a natural conclusion to draw from American action judged in terms of Chinese politics.

At the critical period, when the civil war might have been completely prevented, the men on the spot in charge of American policy were avowed partisans of Chiang Kai-shek and fantastically ignorant of China. General Hurley carried his personal trust in Chiang to the point of refusing to believe first hand reports from American officers when they contradicted information from Kuomintang sources. General Wedemeyer’s knowledge of China can be judged from a speech he made after his return in which he stated that, “The Chinese Empire consisted essentially of feudal dynasties, whose leaders, or war lords, paid tribute to the Emperor.” (This seems to confuse the Chou dynasty, over 2,000 years ago, relations of the Empire with foreign tributaries like Burma or Korea, and the war-lord period after 1911.)

Before General Marshall’s appointment the United States was maneuvered into a false position. The declared objectives of American policy were to repatriate the Japanese and to avoid intervention in the civil war. In fact the Kuomintang troops transported to North China were used entirely in the civil war and actually delayed the evacuation of the Japanese in order to keep them fighting until they were no longer essential to the Kuomintang military position.

General Marshall’s genuine efforts at mediation were cramped by the legal and diplomatic framework within which he had to operate. He could stop new forms of intervention in the civil war, but to discontinue arrangements made by his predecessors would have been a breach of agreement with a friendly government. It was difficult for him to take official notice of breaches of the agreements by the Kuomintang while remaining within the limits of diplomatic correctness. He had to operate in terms of general legal agreements instead of considering practical questions and personalities which would have been much more realistic in Chinese politics.

Except to a small western educated minority these limitations were not intelligible. What was obvious was that the Kuomintang army was receiving American assistance, that American forces worked with collaborationists and Kuomintang reactionaries, and failed to protect liberals from the secret police, and that America made no protest when the Kuomintang repudiated the agreements. It was quite logical to conclude that American policy statements were the conventional euphemisms well known in Chinese politics, and that the real American policy was support for the Kuomintang. Even the western educated group in the Kuomintang who knew that America did not want to support the right-wing have usually felt that the bad state of American-Soviet relations would, in the last resort, always secure American support in a civil war.

At present America is not giving appreciable support to the Kuomintang and this policy may produce the possibility of settlement. If the existing reserves of American supplies are exhausted without securing a decision in the civil war, the Kuomintang, for the first time, will face the alternatives of repudiating its right-wing, reaching a settlement and competing politically with the Communists for popular support; or else losing everything through eventual military defeat.

However the prospect is not very bright. At the best it is likely to be another six months or a year before Chiang Kai-shek gives up hope of a military decision and the longer the war continues the greater the bitterness of both sides. There are signs of Communist policy becoming more extremist and the liberals, especially the independent liberals, have been under great pressure in the Kuomintang areas.

The best hope would be new mediation by the United Nations or by the signatories to the Moscow agreement. International mediation would start with the big advantage of freedom from suspicion of partiality. The difficulties would be to find terms of reference which would enable international mediation to operate and, equally important, to operate in terms of what both parties actually carried out, not merely what they agreed to on paper. Finally it would have to be clear that pressure would be applied against either side that refused to accept mediation or to carry out its agreements. These difficulties are serious but if international organization could overcome them, it would not only bring peace to China but also set a valuable precedent to secure world peace.

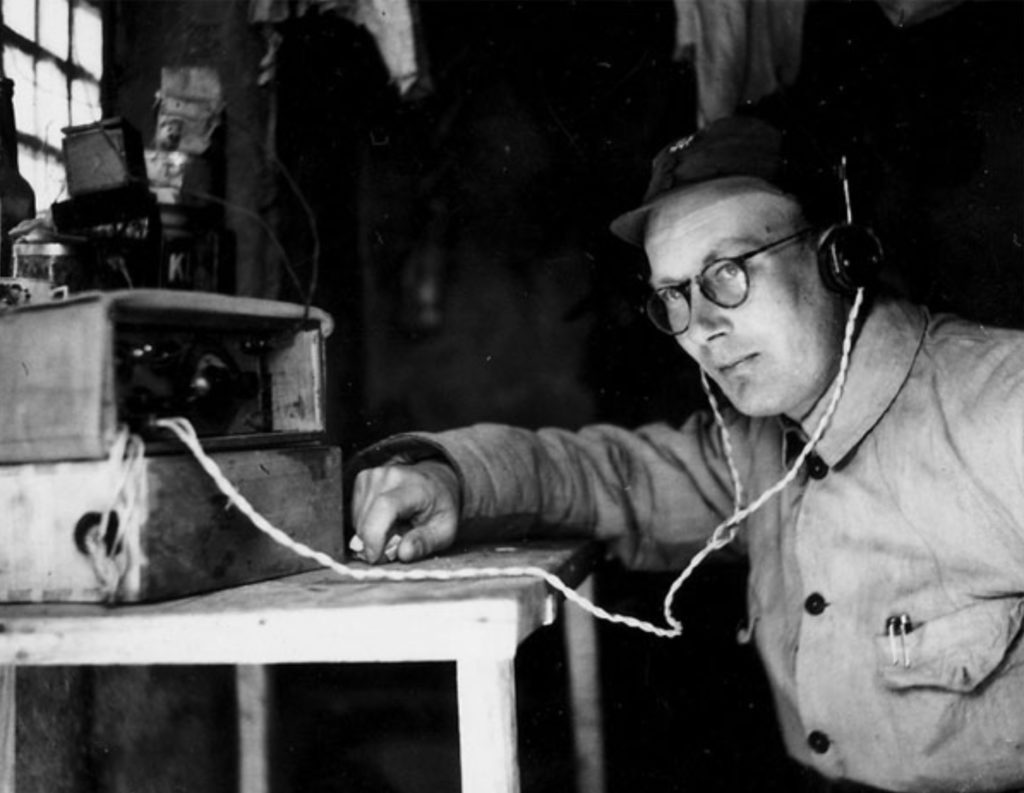

Michael Lindsay (1909 – 1994) was born in London and studied economics at Oxford University. Afterward, he taught in Beijing at Yenching University from 1937 to 1942. While teaching, he met and married a university student, Hsiao Li (born Li Yueying), whose parents were wealthy landlords even though she participated in more radical politics. Michael had already been helping the communists before the Pearl Harbor attack, but afterward he fled to communist-controlled Yenan and assisted the CCP by erecting and managing a broadcasting station. Mao Zedong and other communist leaders personally thanked him for his efforts. When he wrote this article, he was teaching economics at Harvard University. In 1952, he inherited property in Cumbria, England, became Baron Lindsay of Birker, and would sit periodically in the House of Lords (Hsiao Li became the first Chinese woman to be given the rank of lady in the English peerage). He became increasingly critical of the Chinese communist authoritarianism, such as during a 1952 George Ernest Morrison Lecture at Australian National University, where he taught. He was refused entry back into China until after Mao’s death. In 1959, Baron Lindsay moved to America to teach at American University in Washington, DC, and taught there until his retirement in 1975. He lived in Chevy Chase, Maryland, until his death in 1994.

“Debate on China,” by A.J. Brace

July 7, 1947

In the March 31, 1947, issue of Christianity and Crisis, Professor Michael Lindsay’s article, “Is a Settlement in China Possible?” once again is an indication of the oft-repeated statement that a case for any point of view on China can be made by piling enough selective evidence.

After twenty-five years in West China as a Y.M.C.A. Secretary and teacher of Modern History (Current Events) in the Chengtu Provincial University, as well as many years acting as A.P. Correspondent, I have watched the rise of Communism from the coming of “Comrade” Borodin from Moscow to China in 1920, and know something of its deleterious influence while it has eventuated in an armed opposition party which no modern Free State could tolerate in the Western World. As Edgar Mowrer recently stated, “What was a virtue in Abraham Lincoln cannot be a vice in Chiang Kai-Shek.”

It is easy for Professor Lindsay to state “Chiang -Kai-Shek’s sympathies are clearly with the right wing,” but that does not tell half the story. There is no mention of the fact that throughout the war in Chungking, Chiang permitted the publishing of a Communist newspaper, and was always on friendly terms with the Communist leader, Chao En-Lai, who had freedom of access and exit at all times. Also, after Mao Tze-Tung, the No. 1 Communist leader, sat in for six weeks with Chiang Kai-Shek in Chungking, he stated: “70% of our problems are settled, and we can dispose of the rest by friendly negotiation,” but the view was not accepted by his confreres and Russian advisors at Yenan.

Professor Searle Bates, of Nanking University, in your issue of October 28th, probably makes a better case when he states: “As Communist demands have been sharply raised and varied, these men [Chinese and American friends committed to a compromise] have insisted that the government must accept them promptly and completely or be responsible for war.”

Professor Lindsay heaps his scorn on “Government Secret Police,” but says not a word about Communist Secret Police, concentration camps, and summary methods of liquidation. Dr. Lin Yu-Tang and Dr. Walter Judd have reported these fully in their writings.

So many of our Western “Innocents Abroad” whitewash all the Communist faults and smear Chiang Kai-Shek and other leaders who carry heavy responsibility. One does not have to condone the victims of the reactionaries in the government to make a fair appraisal of Chiang Kai-Shek. Dr. Leighton Stuart, our new American Ambassador, as reported by our press, coming back to U.S.A. after three years in a Japanese concentration camp, said: “I have the highest admiration for Chiang Kai-Shek. It distresses me to hear ignorant perhaps malicious misunderstanding of him. He is kept in power by the Chinese people, not by any political machine. He is not a Dictator, but expresses the will of the people, and personifies what they want at this time. His permanence is due to the people, and their retention of him is a tribute to the people themselves.”

General Marshall’s message of 2,000 words reveals the danger in both “Kuomintang dominant groups of reactionaries” and “dyed-in-the-wool Communists who do not hesitate to use the most drastic measures to gain their ends!”

Dr. Van Dusen, in your Sept. 16th [1946] issue, is quite right when he says, “The Chinese Communists are committed to a single aim—domination of all China. ‘Peace’ with those who oppose them can never be more than an armed truce until the favorable moment to strike.” We have enough evidence from Europe, such as Yugo-Slavia, that this is the procedure of Chinese Communists who would not tolerate an opposition party if they were in power, and this is what they criticize in the National Government. If the Russians had not permitted them the use of vast stores of Japanese munitions, the civil war would probably have ended before this. If the Chinese Communists gain power in China, with one quarter of the human race, then the stage is well set for World War III.

It is very easy for Professor Lindsay to say, “The New Constitution is worse than the January agreements!” But it is precisely the January agreements that are included in the New Constitution, which the Communists refused to accept and again raised their ante of unreasonable demands.

Summing up, whether in Asia or Europe, it is clear that there are two conflicting ways of life; one based on Marxian Atheism and class warfare, the other based on Christianity with all our imperfections, but standing for Liberty and the “Four Freedoms.” We must face the issue, be objective, take our stand and express our convictions without hate or the spirit of revenge.

A.J. Brace spent 25 years in West China as YMCA Secretary.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024