“Divided China,” by M. Searle Bates

October 28, 1946

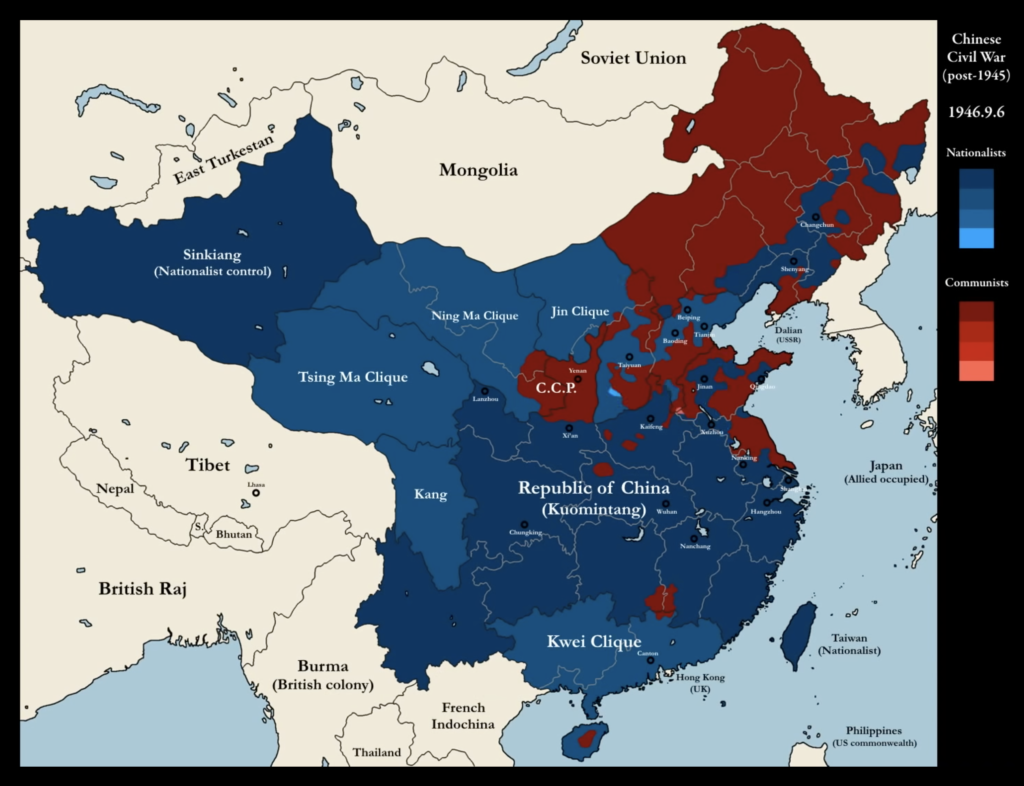

A year after the Japanese surrender, China is not within sight of peace, or of the road to economic recovery. At best, the tasks of restoring a country neither unified nor developed before the war, now broken and impoverished by eight years of struggle and exploitive occupation, were stupendous. Those tasks have been postponed and increased by the actual division of the country into two armed states threatening war against each other; by the Communist wrecking of railways and sealing-off of mines and other important economic units; and by the inability of trade, manufacture, and public finance to right themselves under such conditions.

If one feels that the need and the hope of a communist revolution are so great as to outweigh all other considerations, there is nothing to discuss. If one hates and opposes every enterprise labeled communist or revolutionary, or in fact disturbing to the established order, there is also no need of discussion. Less easy is the position of those who appreciate the necessity of drastic reforms long overdue, and therefore cannot give hearty support to the present (Kuomintang) Government against the Communists; who do not want to oppose the values found in some elements of the Chinese Communist program and practice, but who cannot agree with much that is said and done by them; or feel that their present course is now or in the foreseeable future for the best interests of the Chinese people. Unless there can be developed a far greater force of independent liberal thought and action than has yet appeared, the real democrat, the real progressive, is condemned to stand by while two illiberal parties ruin the country, or to lend a reluctant and dubious adherence to one of these two major parties. The so-called “third parties” are insignificant factions of politicians without popular following, used as pawns by the chief parties, and so far, chiefly to the propaganda advantage of the Communists under the specious name “Democratic League.”

The Kuomintang, inseparable from the National Government which it created, holds three-fourths of the country and the main machinery and responsibilities of national organization. It can claim many important achievements, and it kept the country going through the exhaustive war. The original revolutionary or reformist impulses and slogans are completely muffled in bureaucracy and senility. One must admit that war, inflation, and the armed threat of communism do not, anywhere in the world, make an atmosphere favorable to liberal reform and reconstruction. But the pains and disappointments of the people have been sharpened by the notorious increase in corruption and the pervasive decline in public service. Since severe criticism of the Communists must be recorded, let it be plain that the Kuomintang now commands little respect and no enthusiasm. Except for the fact that it is the only visible alternative to Communist violence, dislike of the Government would be more vocal and active.

It is widely believed, and probably with reason, that the Communists are emboldened by Russian counsel to increase continually their demands upon the Government. At the very least, one must think that Russia would not permit the Communists to be crushed, since they provide such an easy channel of influence with which to bedevil China, the Far East in general, and the United States, so intent on a Far East, set toward peaceful democracy in the American rather than in the Russian definition. If it were not for these Russian connections and potentialities, the Chinese Communists would have fared much worse in both Chinese and Western publicity. The desire to avoid controversy with Russia is a powerful deterrent to anti-communist speech or action; and the Chinese Communists, perhaps the Russians also, joyfully exploit this degree of immunity.

No wholesale aid, perhaps no material aid whatever, has been furnished directly by Russia to the Communists. The Communists have acquired in Manchuria considerable stocks of Japanese munitions which the Russians would not have put in their way if the latter had been faithfully upholding the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, dated August 14, 1945, the very day of the completion of the Japanese surrender. In the exchange of notes accompanying the Treaty, Molotov thus committed his Government: “In accordance with the spirit of the above treaty, and for the implementation of its general ideas and purposes, the Soviet Government is ready to render to China moral support and assistance with military equipment and other material resources, this support and assistance [to be] given fully to the National Government as the Central Government of China.” Such support as has been given was contributed rather to the Communists who seek to overthrow and supplant the National Government.

Center of Gravity Among Chinese

The Soviet Army has stripped Manchuria of essential mining, manufacturing, and railway equipment, leaving an economic wreck. The Russian argument for war booty is simple and satisfactory in Moscow, but nowhere else. Russian withdrawal has reduced Chinese fears. But it was managed in a manner to hamper the entry of the ill-prepared Nationalists, who could not risk conflict with the Russian troops; and to assist the occupation of a large part of the land by Communist forces. A portion of the Communist soldiers in Manchuria have been trained on the spot by Russian officers. It is not surprising, therefore, that China is filled with deep resentment and distrust of Russia.

Nevertheless, the tendency of many Chinese to put upon Stalin’s Russia the main responsibility for the internal conflict—and of a smaller number to put it upon the United States—is not sound. The Russia of Lenin and Trotsky might be blamed for initiating and fostering revolutionary communism in China. But now the center of gravity is among the Chinese. Perhaps three million Chinese have received thorough training as Communist Party members, officials, or soldiers, and many more have been influenced by Communist schools and propaganda, to organized, deep-seated hatred of the National Government and Army. On the other side, National Government personnel and their families, and the local officials, troops, and police under their direction, have been similarly, if less intensely, habituated to hatred of the Communists. Moreover, the overwhelming majority of educated or politically conscious inhabitants of the extensive non-communist areas, while critical of the National Government, fear and oppose the Communist professional techniques of harsh disturbance and crude severity as demonstrated in the eastern and central provinces north of the Yangtze. They see little hope in Communist leadership and policies, either for the economic improvement of the nation, or for good government with a comfortable yoke.

Undoubtedly the areas longest and best governed by the central leadership of the Communists present a more favorable picture. There the Party organization of the people for local production of simple necessaries, for military action, and for political cooperation of the Russian type, are effective—even admirable in the adaptation of means to end. People are not, however, given a chance to develop for the worth of themselves or of the process. They are developed, according to plan, and for purposes determined in the small group which requires absolute control of the mass. The acquisition and organization of power appear to triumph, among the professional revolutionaries, over all other motives and considerations. If the people are sufficiently organized and indoctrinated, they are not interested in freedom of speech or in any other liberty. Yet no fault can wipe out the considerable merit of practical concern for peasant welfare, albeit in the framework of developing Communist power. And no hostile critic can deny the sheer achievement of constructing a wide-flung state, in fact a totalitarian state wherever it has been consolidated, under highly unpromising conditions.

All in all, the stage has been extensively set for resumption of the civil war adjourned in the face of the Japanese menace 1936–37. During the international war the Communists multiplied their armed forces and their area of influence, a process continued recently not only in Manchuria with a measure of Russian cooperation, but also around Peiping and near Nanking and Shanghai. Generally speaking, the Communists have found peace talks and political parleys to their advantage. The National Government continues to lose prestige in the post-war slump, amid popular discouragement and political failure. Accusations sometimes run to excess and to insincerity, for it is hard to imagine that any government could, in the actual difficulties, have met the needs and expectations of the people. But the responsible authorities who take the titles and the money must bear the burden. Moreover, the National Government, apart from hazy and inadequate perception of its own weaknesses in organization and morale, has been very reluctant to touch off a real war with the Communists. The desires of those who favor a war now, without further effort at compromise, have been continually overruled by at least three main considerations: (1) the elements of statesmanship in Chiang Kai-shek and others, who greatly prefer national unity in peace to military triumph, and who have some sense of the injury that civil war would bring; (2) the fear that war against the Communists entails Russian intervention; (3) the restraining influence of the United States.

Influence of the United States

On the last point more should be said. The Chinese nation and its leaders, apart from the Communist minority, attribute to the United States their liberation from Japan and their major hope for peaceful development in the future. In their acute poverty, weakness, and anxiety, they are inclined to trust and to depend almost too much upon America. The National Government knows that the United States favors democratic liberalization; so it can hardly slam the door of political cooperation in the face even of Communists who maintain a large army and the scarcely disguised aim of completely overthrowing the Government. American public opinion would sharply react against a China fighting itself, and therefore the National Government has long hesitated to oppose by force the Communist acquisitions. The United States defers the loan promised for economic rehabilitation, and further aid in the reorganization of the Chinese army, while the present threat of civil war continues. The National Government greatly needs and counts upon such aid, for broad national and international reasons over and beyond the current crisis; and therefore has tried through a long period to compromise the internal dispute.

The United States can aid China only through the recognized and predominant Government, not in defiance of that Government. On the other hand, unqualified and unlimited aid to the Government runs the risk of maintaining an effete regime against a needed revolution. Furthermore, such aid can easily be accused as an act of imperialism, aiming to bring China under some form of American control or privilege. These difficult issues were clearly faced in the remarkable instructions and statement relating to General Marshall’s appointment as Special Ambassador, November 27 and December 15, 1945:

A China disorganized and divided, either by foreign aggression, such as that undertaken by the Japanese, or by violent internal strife, is an undermining influence to world stability and peace now and in the future… It is thus in the most vital interest of the United States and all the United Nations that the people of China overlook no opportunity to adjust their internal differences promptly by means of peaceful negotiation… The United States and the other United Nations have recognized the present National Government of the Republic of China as the only legal government in China. It is the proper instrument to achieve the objectives of a unified China… The United States’ support will not extend to United States’ military intervention to influence the course of any Chinese internal strife.

The statements call for broadening of the present “one-party government” to provide “fair and effective representation” of other elements. “The existence of autonomous armies such as that of the Communist army is inconsistent with, and actually makes impossible, political unity in China. With the institution of broadly representative… government,” all armed forces should be “integrated effectively into the Chinese National Army.”

To this most difficult and complex dispute, mediatorial services of the highest quality have been addressed with patient diligence. One wishes that from the start they could have operated under the auspices of the United Nations or with explicit Russian approval, thus broadening their base and increasing the hope of their success. But the practical obstacles to such a course were greater than idealistic amateurs can realize.

The Chinese Communists, and their allies—whether deliberate or unwary allies—in America, have made the most of these circumstances. They like the Government, but with much more vigor and persistence in publicity, have represented themselves as angels of peace and progress, threatened by the stupid, vindictive partisanship of their militarized enemies. They have been obsequious to Americans at periods during the war and since the war, when they hoped for American military supplies. When that hope has faded, they have denounced any kind of American aid to China or activity in China, as support of the National Government on a partisan basis—“inciting civil war”; or simply as “capitalistic imperialism.” What would they say of American refusal to continue UNRRA [United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration] aid or other economic cooperation with the Government of Russia or of American aid to a revolutionary movement within Russia, if there could be such a thing?

It is no secret that broad-minded men, well up in the negotiating work of recent months, have been made, by hard experience, to distrust the motives and the truthfulness of Communist leaders. On the other side, some factions of the Government group have not stood for peace or for truth. Certain friends, Chinese and American alike, committed themselves so completely to the task of compromise that any barrier to adjustment was ipso facto condemned. As Communist demands have been sharply raised and varied, these men have insisted that the Government must accept them, promptly and completely, or be responsible for war. The old specter of appeasement arises, however. When avoidance of immediate conflict is made the supreme end, the most shrewd and aggressive seekers after power gain a disastrous advantage not merely over reactionaries, but also over moderates and liberals —even radicals and socialists—who value freedom and the democratic way, and disagree with communist totalitarianism.

Advances of Communism

Communism advances through misery, and promotes misery when that works to the harm of opponents, to the increase of communist power. To prevent the economic recovery of non-communist China seems to be a primary aim, as it certainly is a primary result, of recent Communist activity. Conversely, the failure of other parties and other systems to meet the economic requirements and desires of many—particularly when that failure is gross and notorious—gives great advantage to the Communists. Reform in and by the Kuomintang was the natural course for China, blocked by that group’s lack of the breadth, character, and will to triumph over difficulties admittedly great.

If one lived in Yenan, perhaps he might be more conscious of the reputed idealism, austerity, and simple organization of the Communist leadership. However, it seems that even there the democratic lover of liberty would have to change radically his whole scale of values; and the faults and limitations both of human material and of the rigorous system would become increasingly irksome to a resident in peace time. When one lives in a society crowded with refugees from Communist territory near and far, just plain folks who had little property or none, including many farmers, laborers, servants, peddlers, and schoolboys, it is impossible to feel that the Communists are bearers of salvation. Using bayonets to push “the people” to a prescribed “spontaneous movement”; inviting every local rascal to claim field or house or food by accusing any one who has them, no matter how little; harsh conscripting of young men to fight their neighbors and to destroy the livelihood of whole communities—these widespread procedures appear lower than the faults of the society they break up, and move not toward the good community, but away from it. Naturally many of the Chinese people feel that men formed in Communist-guerrilla techniques of revolution and control, will not be models of democratic virtue and of peaceful cooperation in the skills of city life or of government on a national scale. Grant for extreme cases the necessity of force and craft to achieve, or to maintain, freedom and progress, the current Communist methods can be excused only if one has immense confidence in the rightness of Communism’s visible goal, and in the spirit and the competence of its total leadership to act very differently from the way most of it does act.

We ought not to be found hostile to any move, however crude and preliminary, which is a necessary step toward a finer ultimate brotherhood of man. But claims must be anxiously examined. Yesterday Mussolini, Hitler, and the Japanese Empire were marshalling their peoples for a new “freedom”, a new “justice”, a “new order” which put the national interest above capitalist selfishness. Their critiques of the obvious vices in America, in Britain, or in Russia, did not make good their claims for the extension of their own power. Communist critiques, well founded though they may be at some points, do not carry automatic validation of communist ambitions and communist methods. The latter must stand comparison with democratic socialism, with free labor movements, with the progressive play of mixed economies, with the possibilities of the same effort expended on behalf of earnest reform as is now spent for exclusive revolution. Meanwhile, portions of mankind, perhaps the entire race, will strive and suffer in the great testings.

China’s Future

The China outlook is bad. Real agreement and cooperation between the rigid-minded, suspicious leaders of the Kuomintang and the Communist Party, hardened in full twenty years of conflict and without a young face among them, seems impossible to achieve. The Communists demand a large place in government as a free political party in a constitutional state, while at the same time keeping their armies and their direct government of vast areas. The Government demands the reduction of the Communists to military impotence as the price of political compromise. Each side has plausible arguments to support these major positions, declarations adapted to particular audiences, varied and reclothed in each month’s circumstances. But the positions remain incompatible, the protagonists remain implacable. Word-garments of peace merely drape the readying of the guns, while professional propagandists seek to place upon their opponents the outward responsibility for civil war. If a formula of mediation could be mouthed, would it bring more than a brief, unstable truce?

The dark, miserable prospect of full civil war has hardly three dim rays of half-light: (1) the none-too favorable chance of fresh leadership and reforms or moderation within either or both of the hostile camps; (2) startling growth of third-party men and ideas to a stature that hardly seems possible on present evidence or promise; (3) China’s considerable experience of muddling along in neither peace nor war, futile, logically impossible, disgustingly primitive—but not so devastating as the grimmer, better organized batterings and burnings that advanced modern states provide.

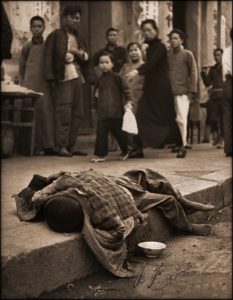

Before you turn away to shrug your shoulders or to pray, think for a moment of the hundreds of millions of peasants and other plain folk, of infants and growing children, whose welfare is the shuttlecock of ambitious contestants, who have neither these strength nor the knowledge to protect their own good. Think also of the elect Chinese who strive in personal insecurity and with small resources to serve their neighbors this day, and to build for a better future. Who is able, then, to speak with indifference, or with heedless partisanship, of divided China?

Miner Searle Bates (1897 – 1978) received a BA from Hiram College in Ohio, was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University, and earned a PhD in Chinese history from Yale University in 1935. During World War I, he joined the YMCA and served in Mesopotamia (then under the Ottoman Empire). In 1920, he began serving as a missionary and taught at the University of Nanking. He was present for the Nanking Massacre in 1937 to 1938, during which he protected Chinese from being murdered and raped by the Japanese army, and saved thousands from starvation. After the war, he was summoned as a witness at the Tokyo Trial and subsequent Chinese trials for war criminals.

“Christianity in China,” by Henry P. Van Dusen

September 16, 1946

In the last days of June and first days of July, I had the privilege of two weeks in China. A fortnight in that vast land of intricate complexities is too brief to justify confident generalization, especially as my visit was confined to Shanghai and Nanking. There was no opportunity to travel widely through the country, to observe conditions in various areas at first hand, or to talk with large numbers of common folk. But introductions and personal acquaintance did open the way for full and intimate discussions with General Marshall, Dr. Leighton Stuart (whose appointment as American ambassador occurred during my visit), Dr. T. V. Soong, the officers of the Chinese Ministry of Education and most of the front rank leaders of the Christian Movement both Chinese and missionary, and for briefer talks with Dr. Sun Fo, Madame Chiang Kai Shek, Dr. H. H. Kung and many members of the government, diplomatic business and church communities. The observations which follow spring principally from those conversations, although the views ventured must not be attributed to any of the persons named.

The Christian Church

It appears to be a nearly unanimous judgment that the Christian Movement in China has emerged from over eight years of war stronger than it has ever been before—probably stronger in membership, certainly stronger in public regard, in spiritual vitality and eagerness for advance. I had no opportunity to verify that judgment, but it was expressed by so many individuals of varied outlook and experience and supported by such strong evidence that it stands beyond serious question.

The favorable position of the Christian Movement is not wholly due to its magnificent record through the years of trial, a record attested by every shade of Chinese and foreign opinion, though that record has undoubtedly had considerable weight in altering the viewpoint of previously critical outsiders. From similar testimonies, two representative statements, one American and the other Chinese, may be cited:

“Today, I am pretty ashamed of myself about missionaries,” writes Randall Gould, for fifteen years one of the foremost foreign journalists in China. “For [previous] condescension here freely confessed I hope that my present missionary friends will forgive me… Japan’s attack on China… was a time of supreme test which Christian missionaries met superbly… No honest person of any race or nationality could watch the Christian missionary in China during Japan’s brutal onslaught and feel anything but fervent admiration.

“Christianity in China has risen to meet its tests victoriously. Its prestige was never higher than at the end of its wartime travail, nor was there ever such prospect for future constructive work.” [Randall Gould, China in the Sun, pp. 282, 285, 300]

And Mr. Gould quotes with approval a tribute of the China Critic, a Shanghai weekly which “had not always been too charitable in its editorial judgments of things missionary and Western”:

“One of the many things that have come out of the present war has been the realization that, whatever doubts may have existed in the past, the Christian missions in China fully and indispensably justify their existence… They have definitely found their place in the life of the nation, fulfilling great human needs in its hour of travail.” [Op. Cit., p. 289]

One byproduct of this changed public attitude deserves mention. As the quotations just given indicate, no distinction is made between Christian Missions and the indigenous Christian Church; both alike receive unreserved praise. In contrast to the period just after World War I when anti-foreign sentiment shadowed the status of missionaries, all schools of Chinese opinion urge return of missionaries, and increased rather than diminished investment of American lives as well as resources in the extension of every aspect of the Christian Movement. Throughout the war years when China was cleft into “free” and “occupied” zones, considerable misunderstanding and mistrust developed between those who migrated, often with great sacrifice and at no little peril, into the unoccupied West and those who elected to carry on under Japanese domination in the East. This cleavage insinuated itself in some measure into relations between Christians of the two areas. There was apprehension that an aftermath of ill feeling might vitiate post-war amity and effectiveness. It is gratifying to be able to record that, within the Christian Movement at least, the differences germinated by wartime separation appear almost wholly dispelled. Christian leaders are facing the tasks of reconstruction in the fullest unity.

More important, however, are the new quality of toughened resilience, the new springs of spiritual vitality, the new spirit of sober resolve yet exultant confidence which were born of wartime testing and now characterize Chinese Christian leadership. In summary, one may report an almost altogether hopeful outlook for the Church in China, with one ominous qualification—the influence upon the Church’s effectiveness of political and economic factors which are beyond its control.

The Christian Colleges

Within the Christian Movement of China, the Christian universities hold a unique importance. One needs constantly to be reminded of this importance. Christians in China, both Catholic and Protestant, number hardly more than 1% of the population (Protestants less than one-fifth of 1%). But almost half of the present leadership of the nation has been trained in Christian schools and colleges, predominantly Protestant. The major influence of the Church upon national ideals and character has been wrought through Christian education. The copestone of this educational structure has been the thirteen Christian universities. Their place in China’s life is discerned when it is recalled that the ratio of college students in China to those in the United States was, before the War, only 1 to 100 and that nearly a fifth of these were in the Christian Colleges. And that, in the land which for centuries has revered learning and the influence of the scholar perhaps more than any other nation. Prime Minister Soong spoke the view widely held among his countrymen when he said in private conversation: “The thirteen Christian Colleges have been one of the decisive factors in the creation of the ‘New China.’ Their importance for China’s future cannot be exaggerated.”

Eleven of the thirteen Christian universities were driven from their lovely campuses, migrated inland, sometimes thousands of miles, and carried on resolutely in refugee quarters, educating in the final year of the War almost double their normal enrollments. This record is part of the noble saga of Chinese higher education in exile—one of the most glorious chapters in man’s agelong quest for learning. Meantime, their properties suffered despoilment and partial destruction under Japanese occupation.

Now, all but one of the groups have returned home and are preparing to resume normal work in the autumn. Destruction of their campuses have been less than was at one time anticipated. But they have been stripped bare of almost every item of metal, and of all laboratory and academic equipment which could not be hurriedly transported into the interior, while their libraries prevailingly were dissipated by the Japanese and sold. To give a trivial illustration, I doubt if two dozen doorknobs are to be discovered on all the buildings standing, though mutilated and in grave disrepair—empty shells containing hardly a book, chair, bed, microscope or desk, not to speak of furnaces, steam pipes, radiators, lighting fixtures, etc. At the moment, they are busily engaged in searching out and buying back their dispersed libraries from second hand bookshops. Imagine the task of reassembling a college library of 100,000 volumes, then recataloguing and reshelving the whole. No one knows how lecture halls or dormitories are to be heated through the coming winter.

Their most serious concern, however, is the maintenance of their faculties. In June, a professor’s salary had an actual purchasing value of about one-tenth the pre-war figure. But the cost of living was rising at an average rate of 25% each month. This means that salaries halve in purchasing power every four months. And the process of devaluation goes steadily forward by geometric progression. There is no way to foresee how life, not to speak of efficiency, can be maintained in the face of such spiraling inflation. The fund of $15,000,000 for rehabilitation and advance which American friends are to be asked to contribute promises to be altogether inadequate to restore and sustain these institutions whose achievements in creating the New China have been beyond estimate and whose potential contributions to the days ahead are measured only by their resources and vision.

Nevertheless, these handicaps do not touch the gravest peril which threatens the future of the Christian Colleges. They are tackling the difficulties of the immediate situation with characteristic patience, shrewdness and determination. All who know their past record and the quality of their present leadership may hold high confidence in the outcome. But these efforts are shadowed by the same ominous factors which we noted in the case of the Churches—uncertainties in the political and economic spheres.

The National Situation

Every forecast regarding China returns finally to a single overarching problem, the present crisis in national life.

I have elsewhere likened China’s crisis to a triangle of three factors—economic deterioration, civil strife, and political incompetence and corruption. And have suggested that this triangle is in reality a vicious circle in which each factor aggravates the advance of each of the other.

The crisis will be resolved in terms of political and economic realities with slight regard for spiritual considerations. But its import for Christian and other constructive institutions is immense. If China is to enter a period of protracted civil strife, latent when not open, it will lay upon all educational and character-forming agencies unprecedented responsibilities. On the other hand, it may impose upon them hazards and handicaps far exceeding those of these recent war years. For example, the Chinese Communists have thus far been cordial to Protestant philanthropic effort. But, should the lines of conflict become sharpened, and both Western democratic nations and Nationalist China, with which Christian leadership is inevitably majorly associated, be identified increasingly as “the enemy,” Communist tolerance toward Christian agencies, whatever their professions of impartiality, may harden sharply. Moreover, it must be recalled that many foremost Communist leaders in private conversation have confessed candidly that, when the day of their victory arrives, they are committed by convinced loyalty to Marxist principals to the liquidation of all religion, “the opiate of the people.”

Again, since the internal situation bears so directly upon Christian concern, it is important that Christians in both China and the West should take the full measure of the present struggle and form dispassionate and sound judgments regarding it. Nothing is more futile than to deny the basically irreconcilable character of the conflict. Common peril from a common foe has effected an armed truce through the war years. Common interest in the face of threatening internal collapse might persuade to a resumption of armed truce. It could not lead to reconciliation, mutual trust and continuing peace. Neither party believes these permanently possible. Neither believes them permanently desirable. The Chinese Communists are committed to a single aim— domination of all China. “Peace” with those who oppose them can never be more than an armed truce until the favorable moment to strike. This basic fact is fully recognized by both parties. In the deeper conviction of both, the question is not whether this struggle must some day be decided by trial of force, probably armed force; the question is when.

In the end of the day, China’s crisis, like almost every other major problem of our distraught world, comes to focus upon a single question: “What does Russia intend? What will Russia do?” Here, especially, is need for clear and candid thinking. And here, the deeper realities are beginning to appear.

The view, until now widely prevalent in the West and to some extent in China herself, that Chinese Communists may be sharply distinguished as to ends and means from Russian Communists, and that the former might be expected to work in continuing coalition with Chinese or democratic and other allegiances, appears to be rapidly disappearing in China. This is a new and important feature in the present situation. Moreover, while Moscow has given little direct affirmative aid to her political kinsfolk in North China, she has latterly strengthened them mightily by leaving in their hands the major part of the vast military supplies seized from the Japanese. The official “party lines” as directed from Moscow and from Yenan run more and more parallel, most recently in a common attack on General Marshall. It is increasingly recognized that Russia’s failure to lend the Chinese Communists vigorous affirmative support is not due, as many supposed, to any deviation in basic ideology or lack of full accord, but to Moscow’s unwillingness to risk embroilment with either China or the United States in East Asia while her energies and resources are wholly required to consolidate her position in Europe and then to effect internal reorganization industrialization in Russia itself.

There are among the considerations which are driving ever larger numbers of liberal and peace-loving Chinese and friends of China to the reluctant conclusion that China may be facing a prolonged future of internal disquiet and division.

The Further Future

I was commissioned to inquire of friends in China, “What are the grounds of hope for China’s future?” Independently but almost with a single voice, they made reply: “The grounds of hope is in the basic character of the Chinese people.” Despite dark shadows over the immediate prospect, I discovered not the slightest slackening of confidence regarding the final outcome. Those who know China best, who have invested their lives in her welfare, are the most secure in their ultimate optimism. This extraordinary people, possessed of unique power to call forth the affection of nearly all who come under their spell so that few who have lived among them escape the nostalgia to return to China, have weathered crises innumerable through an agelong past. They confront the uncertainties, it may be the agonies, of the years immediately ahead fortified by the same indestructible armory of patient endurance, boundless good honor, undiscouraged reliance upon the healing and building ministries of time. Left to herself, China might well weather the present acute storms. Unhappily, she is no longer to be left to herself. For better or worse, her destiny is now intimately linked to the fate of all nations. But of this fact we may be sure: she will not fall through internal weakness, but only if she is swept down in a universal debacle.

More than that. To the whole world’s struggle for survival in which China’s stability is inextricably involved, China will bring priceless gifts of sanity, of fortitude, of sound judgment for the healing of the community of nations.

One further certainty we may stake down. Toward China’s equipment for that service, the Christian institutions in China will continue to furnish, as they have supplied in the past, invaluable contributions. To quote again an observer we have earlier cited:

“Unquestionably the whole issue of mission advance keys closely with the sort of peacetime conditions we are to have in China, whether China herself is to find in peace a chance for real union, leadership, and progress. But even if China does not fare too well in the immediate future, Christian missions have shown their stanch capacity to ‘take it.’ I believe that they are bound to be a leading factor in helping China to find right paths.” [Randall Gould, op. cit., p. 302]

It is doubtful if there is any other spot on earth where the investment now of life, of money, of faith is likely to pay larger dividends for the future, not merely of China, but of all mankind.

Henry P. Van Dusen (1897–1975) served as Union Theological Seminary’s president from 1945 until his retirement in 1963. For his leadership in the ecumenical movement, his portrait appeared on the cover of Time in 1954.

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!

Live in the DC area? Sign-up for Providence's in-person events list!