“Editorial Note,” by Reinhold Niebuhr

September 30, 1946

I send these few random impressions from Germany and will make a further report on my return to America. Only a few weeks ago at the Ecumenical Conferences in Britain many of us were filled with apprehension about reported tensions between the Lutherans of Germany and the so-called “Confessional” groups which was in the forefront in the fight against Nazism. It must be emphasized that there is not a conflict between two churches, because the Confessional group is largely composed of Lutherans, but it desires to retain the unity of the whole church achieved in the fight against Hitler, while some Lutheran State Churches wanted to return to a strict denominational basis. I am glad to report that there is now every evidence that this conflict will abate and that the gains of the past years will not be lost.

“We Germans,” said one of the leading Christians of the nation, “are able to express our Christian faith only in eschatological terms.” It is indicative of the difference in theological climate in Germany and America that this remark must be explained to all but a few American readers. What our German friend meant was that Christians in Germany could express their hope and their faith only in very ultimate terms, or strictly speaking in terms dealing with “last things.” That is to say they are fairly hopeless about the historic situation. Those who have no faith are inclined to sink into despair. Some politically minded people publicly proclaim a facile hope of a classless society and international peace, which they can hardly believe, in the light of the tragic situation.

One man said to me, “The two bearers of the Western democratic tradition against both Fascism and Communism are Christian and Social Democracy.” This is indeed the case; but one might well wish that the hope of Christianity were a little less other worldly and that of Socialism a little less utopian. Neither have learned enough from the other in these tragic years, though I am bound to say that the Christian church seems to have learned more than Socialism. For the church is more active in public affairs than it once was, while the slogans of the Socialist Party have a curiously hollow ring.

Furthermore the historic situation of the Germans is much too desperate to allow much more than the kind of “eschatological” hope which St. Paul expresses, when he declares: “I am persuaded that neither life nor death… will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

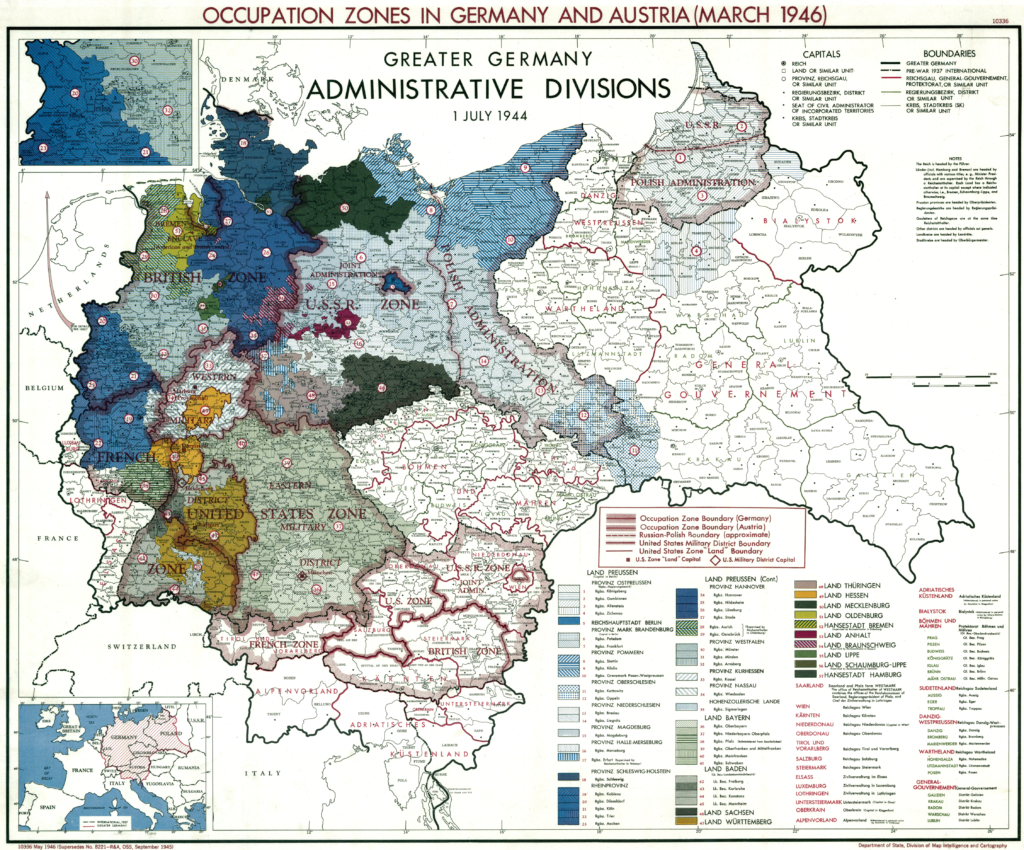

The Germans live in the direst poverty in their ruined cities, with hardly enough food to keep body and soul together. If they were only allowed to rebuild their country—but this is impossible as long as the quadripartite division of their country lasts. Furthermore they are rightly apprehensive that the tension between Russia and the West may not be resolved, in which event they would be the cockpit of another World War.

I reminded my German friends that though we live in luxury, compared to their poverty, that historical prospects were tragic for us too, and that we might become as eschatological as they, though our cities are not ruined. I told them that we had enough imagination to see ruined cities in prospect even though we had not yet tasted the bitter dregs in the cup of God’s fury, as they had.

“Report on Germany: Excerpts from a Personal Diary — June-July, 1946,” by John Baillie

September 30, 1946

Thursday, 20th June. Arrived Bad Salzuflen. Flying over and driving through the country, I thought the German crops looked very rich and promising; the fruit trees everywhere laden; the gardens very fully planted with vegetables and coming on excellently. On the whole the people look well-favored. I saw a good many lanky boys, with skinny legs and sallow faces, but the majority were very different. Many of the people look fat and rosy cheeked. They are not very badly dressed, and many women are very chic; but a fair number of girls and boys were wearing coats and jackets obviously cut down from army uniforms—but well cut down.

Saturday, 22nd June. Starting off at 11 A.M. I was driven to Duren, where I called on Pastor F. I had three and a half solid hours of talk with him. He had been in Dachau Concentration Camp for 3½ years, where latterly 200 people died around him every day. He still suffers from an ulcerated stomach. He and his friends in the Camp all prepared themselves to be shot as the Americans approached to liberate them; but the Americans came too quickly for the Nazis.

F. has a flourishing church. Its seats only 300, but is quite crowded on Sundays for morning service and Holy Communion; and well attended at two week-day services. Before the War it had 200 members; now there are about 1,000. The difference is explained almost entirely by the presence in the parish of large numbers of refugees from Eastern Germany now occupied by the Russians and Poles. These have come to stay. They form, he said, a conspicuously thankful congregation. “Thankful for what?” I asked. “Thankful for the opportunity of hearing the Word of God,” was the reply.

F. was convinced of the necessity of the Church’s finding new means of ministering spiritually to many eager “seekers” who are willing to listen, but had inhibitions about actually coming to Church. They have been so remote from the Church, that so much as to pass through a Church door would for them be going a long way. He said it was certain that many of the youth really wanted to know about Christianity. He instanced a case where a fellow pastor, anxious to interest the youth of his parish, proposed a public lecture on Goethe’s Faust, only to be met with the reply, “We don’t want to hear about Faust. We want to hear about Christ.”

F’s main political concern at the moment was his conviction that it was a very great mistake to hold the elections as early as October. His reason was that the Germans were not ready. We British did not realize how mentally ill (Geisteskrank) Germany was. Voting at the elections would not be based on political convictions; for few Germans had such. Here most would vote for the C.D.U.—The Christian Democrats; in Bielefeld, which F. also knows well, most would vote for the S.D.P.—the Social Democrats; but in both cases the voting would be determined by “materialistic considerations,” i.e., men would think only of whether their affiliation with this or that party would be likely to bring them material advantages. Men think only of the struggle for food and a job.

The Communists would get little support. And Communistic conviction was even less than such support might indicate. F. disagreed with those who say that the down-and-out condition of Germany would breed nihilism. Nihilism is a deliberate philosophy, with a fanatic element in it; whereas what the present conditions bred was rather an utter dullness of soul, a meaninglessness with an absence of all philosophy. People, he said, talked much of the coming War between the West and Russia. He said that they wanted this war to come; it was not a case of merely fearing that it would.

Monday, 24th June. I drove to Mennighüffen, and had a long talk with the Lutheran Pastor. He is one of the prominent young churchmen, reputed to be an outstanding preacher. He spent three years in Dachau Concentration Camp. Mennighüffen is a community of 6,000 souls. Of these about 1,500 now attend Sunday morning services. Also they get 600 children (included in the 6,000) at Sunday School. Mennighüffen was much affected by the revival in this part of Germany in the 19th Century, and the good effects are still felt. They are a church-going people. Recently there has not been much sign of further revival, but a good many who had stayed away from church during the period of Nazi ascendancy are now coming back.

The Pastor thought there had been an evident deterioration in the attitude of the Germans towards the occupying British. He said there were all sorts of grumbles. People were resentful that so many suspected Nazis, who were not true Nazis at all, were kept on indefinitely in the prison camps, without any knowledge as to whether they were going to be kept for three months or three years. He thought the whole administration of the de-Nazification policy was bad. This was his own chief grumble against the British. But the people had other grumbles. Most of these were stupid, such as that proceeding from the widespread belief that the British were eating German food, especially vegetables. He spends a good deal of time trying to debunk these rumors; but (a) some of them are so circumstantial as to be hard to debunk (entmächtigen) and (b) he has to be careful not to compromise himself by appearing too much as a defender of the British.

Most of the people in his parish were without any political interest. The C.D.U. (Christian Democratic Union), being a new party, was little organized. Older parties such as the S.D.P. (Social Democratic Party) might therefore secure more votes in October. There was little Communistic sentiment here, but he thought it growing in the Ruhr and such places. A year ago the fear and hatred of Russia had been universal, but this had changed somewhat, as some people now said that things were better in the Russian Zone than they are here. I asked the Pastor if he believed this. He said, “No.” His sister and her husband are in the Russian Zone and they report that things are very difficult. The Russians have a graded system of rationing—A cards, B cards and so on; and old people get very little. Reports from the Russian Zone are so contradictory that it is difficult to know the truth.

The Pastor thought the Protestant Church in Germany was faced with a serious choice between the view of Marahrens and Meiser, who stand on the ground of their own Lutheran or Calvinist Confessions, and the view of Niemoeller and his friends of the Bekennende Kirche, who stand on the ground of the Barmen Confession. People are very critical of Niemoeller. Many pastors are critical of him on the above grounds. But others as well as pastors are critical of his talk about German guilt. Niemoel1er had preached in Mennighüffen some months ago.

Three thousand people flocked to hear him, and he had so won them that they were uncritical of him; but others who had not heard him were critical. The Pastor said that in the prison camps in Germany there really is something of a revival of Christianity.

Thursday, 27th June. I drove via Cologne to Bonn. The University Building has been destroyed. The library had been removed for protection from the air raids, but is in the French Zone, and the French will not give it (or anything else) up. There are now 3,000 students studying in Bonn. Of these, 95 are students of theology in the Protestant Faculty, 100 being so far the quota allowed. There is no lack of candidates. But there is no real university life. There are no student societies of any kind, and nothing of the old Verbindungen. Classes are held in various houses or other buildings, and students taking different classes never meet. The students would find it difficult, if not impossible, to live on the rations, but (1) they have now a mensa academica for mid-day meal, consisting of “a large pot,” for partaking of which they have to surrender food-tickets, but “only a few” of these, so that it greatly advantages them; (2) many get parcels from their homes in the country; (3) they mostly disappear from classes at the week-ends, seeking food in the country, and many doing a day’s work there on Saturdays and getting their dinner in return. They told me no clothes were available; the shops were quite empty now; they had been almost empty during most of the war—since 1942. New shoes are absolutely unobtainable. The Dean said the suit he was wearing was about 12 years old. But I could not have told it was not a new one! And I have been impressed by the fact that the clergy I have talked to were very well dressed in formal black clothes.

Tuesday, 2nd July. I drove into Berlin. Professor S. is professor of Pediatrics in Berlin University. The University is in the Russian Sector of Berlin, and is accordingly under Russian Control. There is a Russian censor for the University, to whom S. has to submit precis of all his lectures before delivery, and who examines in advance all textbooks that are used. However, so far the censor has let everything pass. S. thinks it stupid that medical lectures should thus be subject to supervision, though lectures on history, economics, etc., might be.

The Russians have commandeered and removed most of the laboratory equipment from the University, so that it is working under the greatest difficulties. Also in all departments they are short of teachers, because no university teachers now in the other zones of Germany will accept calls to the Russian Zone, not wanting to live there. But they have no lack of students; and parts of the University buildings are usable. He says that the Russians with whom he comes in contact seem to him crude and ignorant but almost disarmingly childish.

I then drove to a suburb and called on Frau Dr. S. She too said she found it barely possible to live on the rations. She seemed excessively thin, certainly it is the older people who grow thin here. From time to time she is able (through intermediaries) to make purchases on the black market, of butter, sugar, etc.; but she is trying to save up most of this for her son against his home-coming. She fears the coalless cold of the coming winter. She showed me her fingers, which had largely lost their nails through frostbite in the house last winter. She had tried to write, working in bed, but “es ging nicht” —it did not work.

The Russians are organizing all youth activities in what they call the Free Youth Movement (Freie Jugend). They were trying to get the Y.W.C.A. to come into this, but the leaders are standing firm against it, in exactly the same way as they had refused to let the Y.W.C.A. be a part of the Hitler–jugend. The Freie Jugend is of course Communistic in intention and tendency. “Formerly all was black, now all is red; but it is otherwise essentially the same situation.”

Yet Frau S. had some things to say in favor of the Russians. In the matter of de-Nazification, she thought the Russians were behaving most intelligently; the British were next best, but not very good; the Americans were much the worst, their method being both crude and cruel.

She was very hard on the Americans in the American sector of Berlin (in which she lives). A year ago they were given a great welcome by the Germans; now the Germans hate them with a bitter hatred. One example of their behavior is their madly furious driving through the sector; they are constantly running over people, and they never stop to look whether the man they knocked down is dead (which often he is) or alive. She said that slightly over half the cases in the German hospital in her quarter were people run over by the Americans. Yet in saying this, she spoke very objectively and understandingly. She knew, she said, what the Nazis had done in so many countries of Europe—much worse than anything the Germans were suffering now. She thought the behavior of the Americans was understandable, though grievously mistaken. Frau S. said that a year ago she considered National Socialism quite dead in Germany. Now she is not quite so sure, owing to the mounting tide of opinion against especially the Americans.

Wednesday, 3rd July. I drove to another suburb of Berlin and called to see Pastor G. and his wife. G’s attitude to Russia and the Russians was different from that of any of the churchmen I had so far seen. He takes the view that the Germans must learn to get along with them. He says that on the whole, and apart from individual cases, the attitude of the Russians to the German church in their zone is “correct.” There is no interference with Church activities of the narrower kind. General relations between the Russians and the German population vary from place to place, depending on the local Russian commander. But many German youths are deported into Russia, and there is no further word from them. At first many cattle were driven away, and farm implements were collected and taken, but this is now at an end. When the Russians first came in, there was wholesale rape of women—of all ages, 14 to 70.

G. thought the German Communists were more mischievous in their attitude than the Russians themselves. He thought that many of the things laid at the door of the Russians by German Churchmen were owing to the German Communists—at whom, he said, the Russians laughed. Yet he thought it a great mistake that nearly all his fellow-churchmen should remain so suspicious of everything belonging to the left, using Russia, Communism, Bolshevism, and Marxism as synonymous terms. He was ready to acknowledge an element of idealism in the Russian regime that had been absent from National Socialism. He deeply regretted the formation of the C.D.U. party. He characterized this as a “catholicization” of the Protestant Church. He thought not all Christians should belong to one political party, forming a Christian bloc against the others. He would like to see some Christian Social Democrats; and would not object even to some Christian Communists.

He thought that, though the Russian soldiers had wrought great havoc when they came in as conquerors, and though the taking away of factory and farm equipment and livestock had made conditions terribly difficult in the Russian Zone, yet the Russian authorities were now trying their best to administer the Zone well.

I drove to the other end of the suburb. There a two-day meeting of the Synod of the Bekennende Kirche was in process. Some 80 to 100 clergy sat down to lunch. This consisted of vegetable soup— a clearish liquid very full of whole green peas and a small amount of potato (there being now a potato famine in Germany). There was also, I think, a tiny amount of onion in it. It was well-seasoned and palatable. Nothing else was served, not even a bit of bread to eat with it. Most of the men took three large plates of it. But for three who came in very late nothing was left but the thick pease porridge at the bottom of the pot, with absolutely no liquid; yet I noticed that they slowly chewed their way through two large platefuls of it—I should say they each ate two pounds of the stuff. I had a brief talk with Bishop Dibelius, and a long talk with three of the leading churchmen of Berlin.

I told them of my talk with G.; R. and L., at least, were quite out of sympathy with him, and followed the usual attitude toward both Russia and Marxism—Communism. They greatly distrusted G’s statement that the Russians were “correct” in their attitude to the Churches.

The clergy present at the Synod had come largely from the Russian Zone of Germany, a number of them from Pomerania and Silesia. They had had great difficulty in getting permission to travel, and means of travel; and some had slipped through without permission. They seemed very poorly clothed, and many seemed solemn and oppressed—very cheerless-looking. I asked if any were there from that part of Silesia which is now part of Poland. They said one had come, and I asked to speak to him. He said the Germans were all being deported from that area to westwards. The pastors were being allowed to remain and continue their work until the Germans had all been deported, and then they too would have to leave. He said the presence of a British Mission in this part of Germany was the only alleviating circumstance; not that this Mission had power to do much, but that their presence prevented the Poles from being more extreme in their oppression than they actually were.

I then drove into the center of Berlin. There I visited the Church Representative on the newly formed City Council. He agrees with G., being only the second of this way of thinking whom I have met. It is his business to work together with the Communist, Social Democrat, and other members of the City Council and also to negotiate with the Russians in all matters concerning the Protestant Churches. His view is that the Germans must learn to get along with the Russians.

Personally he gets on with the Russian officials fairly well. They are quite friendly, and he thinks that in a sense they are anxious to do the right thing. Their policy is to be neutral in religious matters. Previously there had been in Berlin various anti-Christian organizations, but the Russians have suppressed these. They give freedom alike to Communists and Christians, but will not allow either to engage in active propaganda against the other. The local Russian authorities have instructions to follow this neutral line, and he thinks they are really trying to follow it.

The great fear in Berlin, as elsewhere in Germany, is of mass unemployment, which the Germans think may soon develop. They say that especially in the Russian Zone the factories are standing smokeless. I asked some of the Berlin clergy whether they knew anything of religion among the occupying Russian forces; but they said they had never heard ofsuch a thing as a chaplain or service of any kind among the Russian troops.

Sunday, 7th July. I drove via Hannover to the village of Gross Burgwedel, where Dr. Hans Lilje (Assistant Bishop of Hannover) was today holding a Youth Rally (Tag den Jugend). There were present about 200 young men and women, students in the higher classes of the schools and in the Technical Veterinary and Teacher-Training colleges of Hannover City. The day started at ten o’clock with a service in the quaint but large beautiful village church. Lilje preached an excellent sermon which rose to heights of real eloquence on “Holy, holy, holy, Lord God Almighty, etc.” from Isaiah VI. He told us many of the young people would be inquirers rather than believers, but they all listened most intently.

We then proceeded to lunch in the open air. Lunch consisted of an Eintopf (single dish); enormous pots of soup filled with various vegetables, which was ladled into the billy-cans the young people had brought with them. They had to give up food-tickets for it, plus half a pound of potatoes per head which they also had brought with them. I saw one girl lucky enough to get a piece of meat the size of a sugar-lump out of the pot, and the others laughingly congratulated her.

There was a queue of young fellows and girls wanting to speak to me after lunch. One young man told me he had been a prisoner in Russian hands near Moscow for two years. He had been most impressed by the piety of the Russian peasants, and of the constant use they made of the prayer-place in their houses. But he thought the Russian Orthodox Church now resembled the Deutsch Christen, in that they had compromised with Communism as the others with Nazism.

We returned to the hall for a question period. During the hour that I remained, all of the questions asked concerned the Atomic Bomb and the era of atomic power. I did my best to answer them, rose to go, and was given a tremendously hearty send off.

Monday, 8th July. I drove to Hamburg. In the afternoon I called on Dr. Freytag, one of the leaders in Foreign Missionary enterprise in Germany. He spoke to me of the attitude of German youth to the parties now forming within Germany and to the coming German elections. Many, he said, refuse to have anything to do with any party, saying “We joined a party once—the National Socialist—and had high hopes of it; but it had brought us nothing but misery; and now it brings us under suspicion. It is safer, then, not to identify ourselves with any party. Everything is fluid, times may quickly change again, and new party allegiance bring us once again into disfavour.”

Many others, though less naive, still hesitate. The Communist party they consider to be merely “National Socialism turned red.” The Christian Democratic Union they think of as essential “Catholic” in the sense of following the R. C. political line—and as having no clear program. Neither do they trust the Social Democrats; thinking they have nothing new to say.

Youth feels that all three parties are merely resurgences of pre-War and pre-Hitler ideas, and therefore now out of date; because entirely new ideas are demanded. I asked him if he thought the elections were being held too soon. He replied, “A year later would be still too soon.” He also said the propaganda now being practiced by the parties is turning people against them, because they now distrust all propaganda. He thinks the result of the elections will give little idea of the real state of German opinion.

Dr. Freytag thought that the present state of German youth presented a real opportunity for evangelization. Many are genuinely anxious to find a new basis for their lives. He complained of the number of men who are confined in our “concentration camps” (as all the Germans insist on calling the Internment Camps) without any good reason, without trial and often without being told why they have been arrested. More and more Germans are saying: “It is exactly what the Nazis did. We thought England was a Christian country, but now we see that in this they are behaving like the Nazis!”

Thursday, 11th July. Making an early start I drove through lovely country to Marburg. I first spent a little time in the University which presented a busy scene, students male and female, dressed in light summer clothes, standing everywhere talking in groups or rushing to some lecture. There are now 4,000 students. The University has not suffered physically, except for the Eye-Clinic, which was near the station—the one-quarter that suffered destruction. Marburg is, of course, in the American Zone.

After lunch I called on Professor Heinrich Frick, the theologian, and his wife. They received me with eager cordiality. I talked to Professor Frick for three solid hours. I asked Frick what were his hopes or fears for the future of Germany. He began by saying that he was, and had the reputation of being, naturally an optimist. But, having said that, he said he was convinced that worse days still were in store for Germany. Germany was now in a situation parallel to that of 1919, but ten times more aggravated. After 1919 had followed (a) inflation, (b) despair, and (c) the rise of National Socialism—in that order. These things were bound to come again, by the same logic, unless something drastic were done to prevent it.

There must be a different attitude on the part of the conquering nations from what there was last time. It looked, however, as if things were going to be worse this time, not better; and that was why he was pessimistic. Germany, always over-populated, was now having an impossibly large population packed into a much reduced space. In the East it had lost vitally important territories to Russia and Poland; and the populations of these territories were being driven into the remaining overcrowded area. German factories had been destroyed, and many of those that remained were being dismantled. And the present division of Germany (of what remained of it) into four zones, separately governed, and with virtually closed frontiers, was quite crippling.

John Baillie (1886 – 1960) was a Scottish pastor and theologian who served as a professor at Edinburgh University from 1934 to 1959 and as the principal of New College and dean of the Faculty of Divinity from 1950 to 1956. He wrote A Diary of Private Prayer (1936) and with John T. McNeill and Henry P. Van Dusen helped edit the Library of Christian Classics series. From 1941 to 1946, he was the convener of the Church of Scotland’s General Assembly’s “Commission for the Interpretation of God’s Will in the Present Crisis” (“The Baillie Commission”), through which Baillie helped the Church to think through its approach and mission to the post-war world.

“A Report on Germany,” by Reinhold Niebuhr

October 14, 1946

A month of travel in Germany which brought us into every part of the American Zone and the Berlin headquarters, and permitted us to confer with all sorts and conditions of military officials and German people, leaves one with so many impressions that it is difficult to bring order into them or give a coherent account of them. Yet some impressions are so indelible and vivid that they press for immediate expression. I will limit this report to such impressions and record them in order.

The first has to do with the ethics of occupation. I suppose we will have to be in Germany for a long time. Both the internal situation of Germany and the external European situation require it, and now Germans hope for its continuance, if, for no other reason, because they fear that Russia will come in if we leave. But there is something very ugly in the contrast between absolute power and absolute weakness, between luxury and poverty, which an occupation army creates. Nothing is spared to make the American soldier, and more particularly an officer, comfortable. And little is done to make the almost intolerable lot of overcrowded Germans a little easier. Thousands of German families are still being evicted and forced into already overcrowded homes to make room for our officer-families. Furthermore the manufacture of glass, furniture, electrical appliances, etc., is almost exclusively for the benefit of American installations. The contrast makes sensitive American officers morbid and the less sensitive ones more callous. One wonders whether men are incapable of self-restraint, when the social restraints of power no longer operate.

The contrast of power and weakness is as fruitful of arrogance as the contrast of poverty and wealth is of self-indulgence. Even the best men, who know that no man deserves the absolute power he holds in such a situation, find difficulty in avoiding a certain note of arrogance in their relation to the occupied population. Among the best it assumes an air of patronizing kindness and among the worse, of brutality. An army of occupation is a vivid reminder of the necessity of striving for both equality and liberty as the basis of justice. Where these are lacking, life is brutalized.

II.

One also finds little sense of mutual guilt among victorious nations. The ruined cities of Germany are universally regarded by military men as the inevitable and just retribution for German guilt. Yet the report of our army air force suggests that some of our obliteration bombing was strategically quite useless. The city of Kassel, for instance, was destroyed 80% by British saturation bombing, simply to make quite sure that no factory would be rebuilt. Twenty thousand corpses are still within the ruins. Even if all this should have been necessary, conquerors might well pause in humble and contrite recognition of the fact that we have reached a dubious state of historical development when such things are either possible or necessary. One wonders when one studies the attitudes of armies of occupation, whether nations, as such, ever display the sense of mutual guilt which the Christian gospel prompts, or whether that must remain to be the end of history— a possibility for individuals only.

My second most pressing connection is that the greatest evil of history is the vindictive passions of men. Masked by the idea of justice and breeding new evils in the name of meting out retribution for old ones. The Nazi evil was very great and the sufferings caused in Europe by Nazi aggression vary terribly. But any punishment which we add and will add beyond that already inflicted upon Germany by her ruined cities and bankrupt economy is almost bound to obscure the sense of a righteous punishment because of a growing sense of the injustice of the retribution. If nations could only learn what is meant by the Biblical word: “Vengeance is mine sayeth the Lord: I will repay.” I have found no greater understanding of the evils of Nazism anywhere than in Germany. The Germans regarded it as loathsome even before they knew all about the horrors of the concentration camps. They have no quarrel with our punishment of the Nazis and sometimes think it has not been severe enough. But most of them resent our mechanical forms of justice, which fail to discriminate between the endless forms of complicity in a collective evil and seek by individual judgment to correct an evil which had a hundred social roots. There are few Americans in Germany who understand the magnitude of the German tragedy or know that some very innocent but very stupid Germans may have contributed more to it than some who were obliquely involved in it in explicit terms. We removed 52% of all school teachers in Germany for instance, in comparison with 5% in Japan. Some of the school teachers were Nazis only in the sense that they were treasurers of the village welfare fund, under Nazi control.

III.

On the subject of Germany’s religious life, more than one impression must be recorded. The outsider, particularly when coming from a highly secularized America is impressed by both the old and the new vitality of the Christian tradition. One notices how deeply rooted Christian institutions are in German history and how for instance, religious instruction in public schools is taken for granted by every one. In our meeting with German ministers of education in the three states of our zone, all three ministers, though two were socialists, emphasized the necessity of Christian Education. One cannot escape certain uncomplimentary reactions about the character of this old religious vitality, as one remembers that it did not prevent the rise of National Socialist paganism, however heroically a portion of the church defended itself against the paganism, once it was full-blown. It would indeed be quite sentimental to forget that German Protestantism was for centuries singularly inept in dealing with problems of social righteousness and in making the gospel relevant to man’s communal existence. I have before me, as I write, a vigorous criticism by a Confessional pastor of the protest which certain church leaders made against our military government’s de-Nazification law. “Let us not forget,” writes the pastor, “that many church leaders refused to hear when we said ‘Hitler means war’, and that the burning of the Reichstag, the corruption of elections, the persecution of Jews, the Ruhr purge, that all these things did not convince them of the evils of the system. Thirty million people had to die before they recognized the injustice of this system.” With this judgment one must concur, and one might add that whatever the great virtues of Rhineland Catholicism, the clericalism of Bavaria seems almost as reactionary as that of Spain, and it was deeply infected by commerce with Nazism, as General Eisenhower discovered when he was forced to dismiss a Bavarian minister-president, nominated by Cardinal Faulhaber, but subsequently disclosed as a Nazi sympathizer. In the same Bavaria, the Lutheran Church, unleavened by Confessional leaven, had about 170 pastors who were close to Nazism.

The traditional spirituality of Germany was not, in other words, a pure resource against Nazism. But the church, both Protestant and Catholic, did also produce some of the most heroic opponents of Nazism and has gained through this heroism, not merely a new prestige in the nation, but a new measure of divine grace. The new vitalities of the church are impressive. When one sees what the church does to help the millions of German exiles from the East, forced into the demolished cities of western Germany, and studies the vast service to the impoverished under the leadership of Dr. Gerstenmeyer, one of the survivors of the attempt on Hitler’s life, and when one studies the new relevance of Christian preaching to pressing immediate problems, without loss of the gospel’s message to man’s ultimate problems, when one gauges all these new facts of vitality, the conclusion at which one arrives is that Christendom has not heard the last from the Christian Church of Germany. It may yet speak a more creative word in life than any other national church.

I have never attended a more moving service than one in the church of Pastor Fricke in Frankfort, held in a bombed out school building, in which the congregation, incidentally, had provided not only for its own auditorium, but shelter for dozens of refugees from the East. The preacher’s sermon was as profound and moving as the surroundings were simple. One felt in fact that it was in such places that the gospel could most fittingly be preached. On a subsequent Sunday we heard, in the only intact church of the once great city of Stuttgart, the brilliant young theologian Dr. Thiellicke of Tübingen expound the ethics of the Sermon on the Tuebingen Mount to a congregation which filled the church to the bursting point. It was the real gospel. The profoundest truths of the gospel were given the most precise and helpful relevance to the daily life of a harassed and sorely tried people. If the world would give Germany half a chance (which it may not either out of stupidity or malice) much grace will flow to all of us from this new life.

Another aspect of the religious situation is the intimate cooperation between Protestants and Catholics particularly on the political level. The old Catholic political parties have become Protestant-Catholic. Karl Barth has warned against the dangers of such religiously sanctified political parties, and most of the dangers he has enumerated are real. The greatest danger may be that conservative political interests will falsely seek the political advantage of religious prestige. But the new Christian parties are by no means purely conservative. There is in fact a possibility that the old struggle between a too individualistic religion and an anti-Christian Marxism will be liquidated. Upon this promising aspect of the situation I hope to make a subsequent report.

Undoubtedly the fear of Communism has been added to a common experience in the fight against Nazism in bringing Catholicism and Protestantism together on the one hand and in creating a new bridge between Christianity and Socialism. These three bearers of Western culture, Catholicism, Protestantism, and Socialism feel themselves united in one past struggle and one future one. The socialist rejection of totalitarianism must be believed. Karl Barth thinks that this development emphasized “Christian Culture” at the expense of Christian faith. In a now famous address in Stuttgart, he declared: “The Christian faith can be maintained even in a well regulated band of robbers.” To which one of the leaders of the struggle against Nazism replied: “Such a judgment is more easily made by one who had little direct experience of the robber band from which we have been liberated.”

It may be that the fear of Communism dominates both the Christian and the Socialist life of Germany too much. But I would want to be sure that Western stupidity does not deliver Germany into the hands of Communism before I would allow myself such a criticism.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024