Moral injury has captured the thought and discourse of thousands around the world. Whether one is a theologian, clinician, ethicist, philosopher, or average citizen, moral injury seems to evoke an inchoate, descriptive connotation of life’s cruel tendency towards dissolution. In academic and professional dialogue, the phrase has generally been located along one of two conceptual axes, connoted by either the nouns betrayal or transgression; however, these two words are not synonymous. The latter term of transgression—currently in professional vogue—certainly carries a sense of the violation of a boundary, presumably deep within a person either as a core value, attitude, principle, or belief. However, though familiar to many from “The Lord’s Prayer” but routinely used in professional discourse without theological overtones, transgression lacks a sense of depth and breadth, and seems to indicate that such a violation, though deeply held, is perhaps not conditional in relation to others, indeed perhaps only to the self.

Not so the noun betrayal. This word, first coined relative to moral injury by Jonathan Shay, also carries a sense of the violation of a boundary, and likewise at a core individual level, but it adds a sense of depth, breadth, and threat applied to foundational relationships. In essence, to betray is always to sever a relationship with another, to the complete rupture of trust in that relationship such that what existed before is now in doubt, if not threatened with permanent dissolution. Betrayal is more strongly expressive than transgression because it is always a function of at least two rather than one, if not even others in its consideration. Again, though not a theological term, nothing evidences this more than the cross, for the crucifixion of Jesus Christ commemorated on Good Friday is the greatest expression in all time of the moral injury between God and humanity. On Golgotha, the existential rupture and betrayal of God by humanity begun in Eden reaches its nadir, and the threat of permanent dissolution to that eternal relationship seems complete.

This betrayal, however, occurs that Paschal week in three deepening concentric stages, each in turn more existentially ominous than the other. The first stage of betrayal begins on Palm Sunday, as Jesus of Nazareth begins His passion by riding into Jerusalem on a colt, the foal of a donkey. As loud cheers of “Hosanna in the highest!” and “Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord!” triumphally ring across the city, the Gospels foreshadow the sense of looming catastrophe. These joyous cries are yet thin and fickle, expressing the temporal misunderstanding of Jesus’s messianic held by the people. By the end of that week, these same people to whom God had promised an “anointed one” to redeem all creation will be yelling their rapture at the release of a murderer and shouting at Jesus’ captors “Crucify Him! Crucify Him!” The sense of betrayal by God’s people during the week is palpable, tragic, damning, and yet inclusive, as theologically, every person who has ever lived is accorded a place in the crowd. Each of us, too, have betrayed Jesus of Nazareth, as surely as if we were there in Jerusalem that fateful day. The biblical text invites us to both sense and know this on a personal level. Yet were we to stop here, perhaps we could be satisfied with self-identifying with transgression as a preferred verb and confine our sense of moral injury only to our personal culpability and need for repentance.

Yet the Gospel accounts don’t afford us this luxury, for we are drawn into another stage of betrayal, expressed by Jesus’ disciples in His greatest moment of needed solidarity. Judas Iscariot, of course, begins this duplicity by selling out Jesus to the temple authorities for a mere thirty pieces of silver, but this treachery is only too visible by half. If it were only that, each of us would be too tempted to foist onto Judas’s perfidy our own rationalizing, self-righteous indignation. Yet again, the Gospels accord us no such option, for just the next night, the remainder of the disciples fall asleep in Gethsemane as their Master prays even unto bleeding. Evincing His consuming pathos at obeying His Father’s call for sacrifice unto death, surely here in Jesus’ earthly life we intuit the decisive moment of His need for brotherly support and filial unity. Yet when Jesus is also arrested and carried off by those same authorities, we cannot be surprised that all of Jesus’ disciples abandon Him in fear and terror. Not one remains to go with Him, or to put at risk themselves though they have pledged Jesus undying fealty. However, lest any reader has yet to imbue the lesson, a still greater betrayal of Jesus awaits in His closest disciple, Peter. As night fades into morning, Peter verbally and publicly denies knowing Jesus three separate times, indicating that even the most intimate of His cohort have now betrayed Him into friendless isolation. All His disciples who had joined Jesus in intimate table fellowship at the Last Supper are now complete in betraying Him of their brotherly love, fellowship and allegiance.

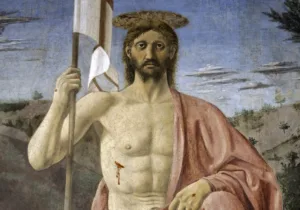

Still, the greatest stage of betrayal of this divine drama awaits Jesus on the cross itself. While the Gospel accounts differ in their perspectives on the tragic and unjust crucifixion of Jesus, they accord us a proximate perspective where we seem to see, hear, taste, smell, and even touch the human toll of Jesus’ unwarranted criminal execution. While Pilate’s abdication of his provincial authority was damning, Jesus seemed resigned to that calculated political rationalization, and even of the thrashing and flogging by those Roman guards assigned the task of achieving His death. However, for Jesus the greatest sense of betrayal awaits on the cross and comes as we hear Him pierce human time with that final, divine cry “My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?!!!” In this singular moment at Jesus’ death, as His body heaves its last earthly breath, we discern a deeper existential threat, the possibility that the Triune God has somehow suffered its own rupture. Even writing these words betokens a sacrilegious bent, yet this is the witness of the text, one which forces us on Good Friday to differentiate between the penultimate and the ultimate meanings of the cross. Here, the concept of moral injury takes on a powerfully evocative and existential understanding, as we are convicted to ask whether the earthly betrayal of Jesus of Nazareth by we His people and His disciples has somehow led to Jesus’ full, human death, but more than that. Has this also led to an eternal dissolution of the Christ’s relationship to His heavenly Father, and the seeming absence also of the Holy Spirit on that deathly summit? Indeed, the final betrayal of the cross invokes our reflection on whether humanity’s betrayal has somehow threatened rupture to the Triune God?

Here at the cross, no answer seems evident to that question, and so human life appears tenuous at best, if not void, without either meaning or hope. The cross challenges us to sense and feel this existential tension, to linger in it, to not move too quickly from it. Indeed, the story of Jesus’ Paschal week arrests our attention with the reality that beyond mere transgression, betrayal lies at the core of this drama, and all relationships now stand under eternal threat of unending rupture. Our own culpability as not only spectators to but also participants in this drama force us to enter the story, and to see our own betrayal of God in every stage of these events. At the end of Good Friday, we are left only with this tension, and the real possibility of life without God.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024