On Holy Wednesday, one evening prior to the Last Supper, Jesus dined in Bethany at the home of Simon the Leper on the southern slope of the Mount of Olives. In the course of the repast, Mary, the sister of Martha and Lazarus, anointed Jesus with spikenard. There’s some confusion as to precisely who all the key players are, including whether Simon and Lazarus are really one and the same. There’s also a question as to how many anointings Jesus enjoyed—or was subjected to—in Bethany over the course of his various sojourns there. Whatever the truth of it, Holy Wednesday is most significantly commemorated as the day Judas decided to betray Jesus. It also provides a profound testimony of the depths of Divine love.

For this reason, Holy Wednesday is also known as Spy Wednesday, gesturing to an etymological correspondence between “spy” and “ambush,” or “ensnarement.” Perhaps indignant at what he perceived Jesus’ indulgence of Mary and the wasteful misuse of precious oil—or, maybe more likely, because of his annoyance that he wouldn’t be able to embezzle the proceeds—Judas slipped away to the chief priests and offered to help them arrest Jesus.

Jesus knew all this of course. That he knew this is evidenced in several things he will say at the Last Supper, indications that he knows Judas has already decided to turn him over, despite surely knowing that the chief priests would have Jesus killed. That Jesus knows all this and yet will still clean Judas’ feet prior to their last meal together is striking. No, staggering is probably closer to the mark. I stressed in Holy Monday’s reflection that Jesus is no pacifist, but he surely is a man of peace.

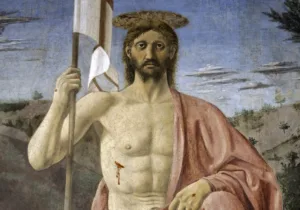

Taking this further, it is shocking to consider that God, omniscient, knowing what humanity would do, would nevertheless choose to bring humanity into being despite knowing human beings would betray his son, slander him, condemn him, beat him, flail the flesh from his frame, and torment him in near-countless other ways before finally, almost mercifully, nailing him to a tree until dead.

I have always found the depths of that kind of love difficult to comprehend.

Outside of depictions drawn directly from the gospels, possibly the best comprehensive depiction of this aspect of divine love that I have encountered is Denis Villeneuve’s 2016 Arrival. The storyline is straightforward: gigantic, watermelon-seed-shaped spaceships touch down at 12 locations across the globe and a team of linguists race against time to unravel the purpose of the aliens’ arrival before increasingly panicked world governments lash out in a global conflagration. I accept that on the surface this seems a strange vehicle for the depiction of divine love. Sure, Arrival is a sci-fi flick about squid-like inter-planetary visitors who come to earth and try to communicate with humanity for the purpose of bestowing upon us some kind of gift—whether some wonderous technology or terrible weapon we do not know. But that’s only a gross description of its major plot devices. Arrival is no more about those things than The Martian was about a poor chump who missed his ride home. Arrival is about grief—an asphyxiating, crippling, overwhelming kind of grief—and about time, communication, empathy, free will, and, most emphatically, love. A love so profoundly abiding that it breaks your heart. Given its source material is a Ted Chiang short novella, it might not be entirely inadvertent that the film provides a God’s eye view of the world.

It’s a difficult film to discuss without spoilers—and the great reveal of Arrival really deserves to be experienced raw. I will only say that at center stage is the brilliant heroine Louise Banks, a linguist tasked with communicating with the visitors sufficiently enough to answer a simple question: What do they want? And while it turns out that the aliens have no interest in colonizing or harvesting or harming us in any way, Louise really is a heroine: as in, for a reason I won’t reveal, she’s possibly the most courageous character I’ve ever seen portrayed in film. In the course of interacting with the aliens, Louise’s efforts to learn their language re-wires her brain and gives her an extraordinary capacity to slip beyond sequential time. She doesn’t gain omniscience exactly, but a profound kind of foreknowledge—though that is probably exactly the wrong word. She develops something more like…precognitive memories of things that haven’t happened yet. In any case, she discovers enough—remembers enough—about what lies ahead that she knows she will someday confront a terrible choice. On offer will be the extraordinary joy of a relationship with someone who will mean so very much to her and who will then be terribly ripped away. Faced with the prospect of such an admixture of intoxicating joy and soul-shattering sorrow, Louise chooses to enter into that joyful grief rather than to spare herself—deprive herself really—and walk away. While we already have it on good authority that not all tears are an evil, I cannot reflect on her courage without swallowing hard on the grief that threatens to rise in my throat. I only hope I could have such courage within me.

This is the point of connection. In the cradle garden, God created human beings so that we might love as He loves—both one another and God Himself. To make this love possible, God was required to construct humanity with moral freedom—for love is free or it is not love. Because the actions of free beings can never be perfectly determined by anything else, this love came with a cost: risk. The risk was the possibility that human beings would revolt against God’s love. Spoiler: revolt we did. That we did is mirrored in the ongoing tug between the two fundamentally conflicting kinds of human desire: cupiditas, which enshrines a form of self-love and tends toward the domination of others, and caritas, an orientation to the good and love of the neighbor. As Jean Elshtain used to put it, this latter kind of love includes a recognition of one’s own interdependencies, an admission able to be made without fear by also recognizing that dependence on others is not a diminution but rather an enrichment of self.

To love anything is to risk heartbreak. To love deeply is to hazard being busted in half and choke in despair. Augustine knew this. He knew that human relationships are fraught with peril. “Who would be capable of listing the number and the gravity of the ills,” he rhetorically asked, “which abound in human society?” These perils, Augustine understood, quoting from a then-popular comedy, maximize within the family sphere: “I married a wife; and misery I found! Children were born; and they increased my cares.” It is not that a wife and children jeopardize happiness. It is that the wife and the children help create that happiness and the prospect of their loss means the carting away of happiness as well. To love is to risk. And the willingness to risk is a measure of love.

At the heart of The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt posits her fundamental claim that the opposite of totalitarianism is love of the other; not a love that loves the value of the object in view—nor only so long as it remains valuable—but a love that simply loves absolutely. She attributes the insight to Augustine:

This mere existence, that is, all that which is mysteriously given to us at birth and which includes the shape of our bodies and the talents of our minds, can be adequately dealt with only by the unpredictable hazards of friend-ship and sympathy, or by the great and incalculable grace of love, which says with Augustine, ‘Volo ut sis’ [I want you to be], without being able to give any particular reason for such supreme and unsurpassable affirmation.

“I want you to be” is a profound affirmation of love. It endorses the ontological distance between subject and object. I want you to be. Love is not satisfied with a replication of the self. Love desires that the other exists, independent and free.

In antipodal opposition to this is the totalitarian will. Elsewhere in her book, Arendt will describe totalitarianism as a will to “domination” striving to “make people anonymous” and “interchangeable.” It is a solipsistic hunger seeking the “destruction of individuality.” In the totalitarian appetite, there can be no “you” to love.

Holy Week confirms that Divine Love isn’t sentimental. God “wants us to be” whatever the costs—even as He knew the costs. Of course, He also loves us far too much to let us “be” just any old way. He knows that human beings require a particular kind of moral ecology in order to flourish. In his ruminations on 1st John, Augustine makes this assertion this way:

You must above all avoid thinking of love as a poor, inactive thing, wanting no more than a sort of gentle mildness for its keeping, or even a careless indifference…. You are not to suppose that you… love your son when you relax your discipline over him, or love your neighbor when you never find fault with him. That is not love.

From this we gather that correction—punishment—can be consistent with love. All of classical Christian just war thinking hinges on this. War can be an expression of love in the last resort. How we fight those we fight can express this love as well.

The Eastern Orthodox theologian Thomas Hopko put the same thoughts this way: “The almighty God reveals Himself as an infinitely humble, totally self-emptying and absolutely ruthless and relentless lover of sinners.” And yet it remains the measure of this love that God will not overrule us. He wants us to be and He wants us to want Him to be. But he will not force it. The great Czech priest, philosopher, and dissident Tomáš Halík—who stood against the totalitarian will—says it well:

[God’s] respect for the gift of freedom—the greatest gift that we receive from our nature—means that his explicit presence in my life (my encounter with him in faith and dwelling with him in love) presupposes and requires that yearning “I want.” God has no wish to break his way into our hearts like an uninvited guest. He wants to enter through the gate of freedom, the gate of yearning love. As the mystics would say: God himself yearns for our yearning.

The catechetical inquiry regarding the chief end of man is properly resolved with the assertion that man’s primary purpose is to glorify God and to enjoy Him forever. We can safely presuppose however that this is only true when humanity is the subject. When we are speaking of the Divine perspective it is surely more true to say that our chief purpose—the end for which we were created—is, in the first place, so that God might enjoy us and know us forever. A part of me trembles to say this, lest the lighting strike—I know it might smack of blasphemy—but I cannot see it any other way. This has nothing immediately to do with our own worth—we do not directly deserve this Holy regard (though the fact of the crucifixion suggests God finds us very valuable indeed). Rather, God loves us because God loves to love. And His love makes us worthy of being loved. I think that’s just how love works.

I do not know how much divine omniscience makes any of this easier to bear. Precisely how all-knowingness and human freedom intersect is a mystery too deep for me to plumb. And I cannot know what can be known for certain and how much is only an endless knowing of all the near limitless possibilities. In any case, whether Jesus had any certainty in Judas’ final end when they broke their embrace in the Garden—or for that matter, whether he had any certainty in my own when he hung on that cross for me—we are not told. But I can only conclude that while we have it on good authority that there is no greater love than when a man lays down his life for a friend, Christ’s treatment of his enemies suggests that strictly speaking this might not be precisely true.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024