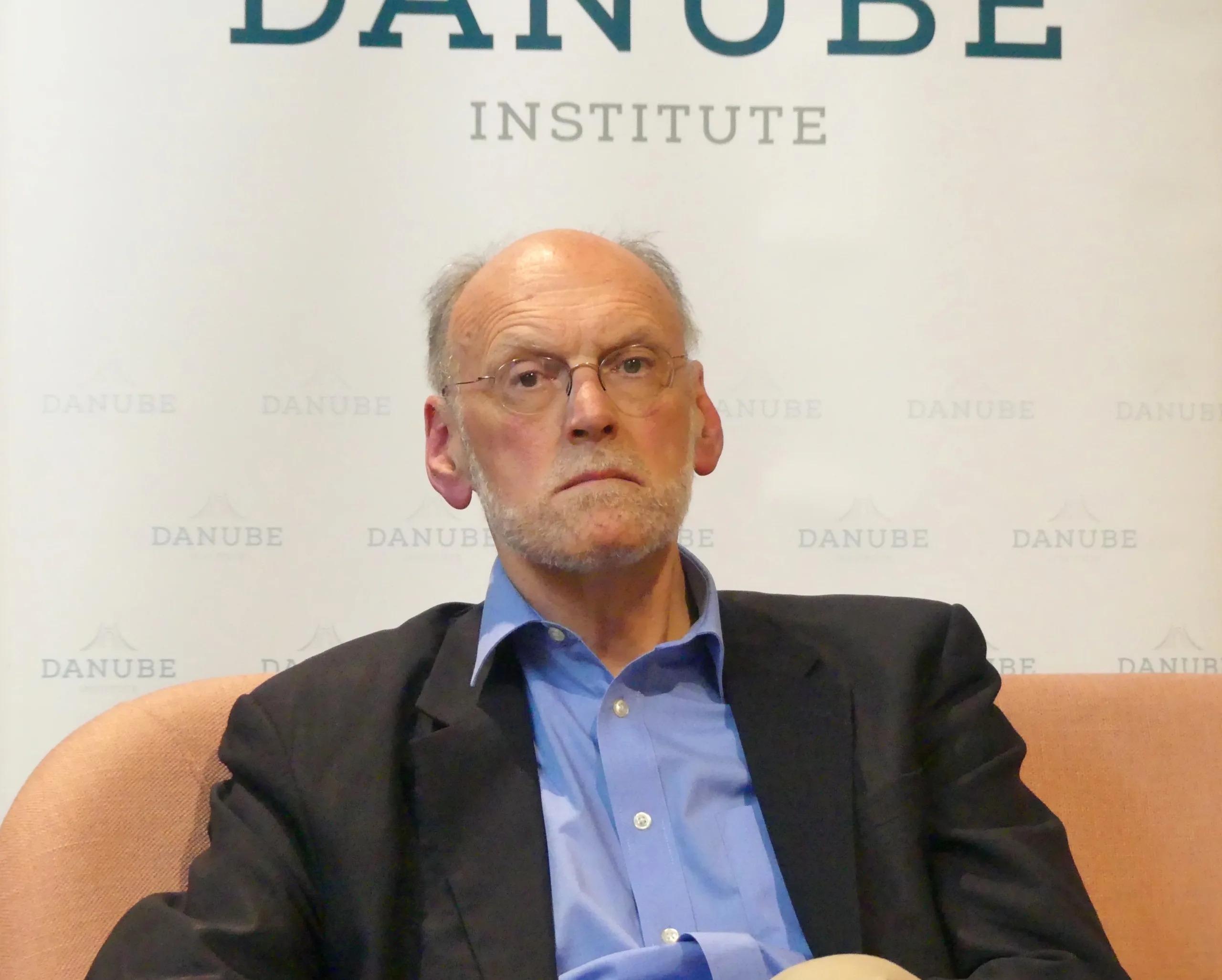

At the Christianity and National Security Conference in Washington, DC, Nigel Biggar, Daniel Strand, and Marc LiVecche participated in a panel discussion about the just war tradition. Biggar covered the tradition for today while Strand talked about Paul Ramsey’s contribution and LiVecche explained Reinhold Niebuhr’s relationship with the tradition.

Rough Transcript

Nigel Biggar: Thanks very much Mark. Can you hear my voice at the back there? Great. Yeah and thanks very much for the invitation to come and speak at this event whose purpose is very close indeed to my own heart. So, I’m glad to be able to contribute to your reflections. Now my aim is to speak for no more than 20 minutes and then I think we have 10 minutes of Q & A and I know we’re starting 12 minutes late, so I want my full 30 minutes. So, the title of my brief set of reflections is wishful thinking or nettle grasping question mark wishful thinking or nettle graspingquestion mark. So, let me take you back I think about 10 years ago, I need to confess as part of the preface to this comment, I supported the invasion of Iraq and I’m not entirely clear whether I’ve found a reason not to carry on supporting it – put that aside, so I assume many of you just will disagree with that, put that aside. Ten years ago I was giving a talk in Oxford on this subject and a friend who was a Baptist minister stood up afterwards and made some comments and then she said but there had to be a better way, there had to be a better way. And I thought to myself well maybe there was a better way I’m not sure I’ve seen it, but why did there have to be a better way? Let me give you another example this is closer in time last Sunday morning I gave a sermon in Christ Church cathedral in oxford on immigration policy. I normally speak out of the scripture but on this occasion I didn’t, I spoke about immigration policy, and among the things I said was that as a rule, economic migrants should be returned home. Be assured I understand, certainly as a Christian who takes the bible seriously, we have a duty of care to vulnerable migrants. Deuteronomy 10 verse 19 y”ou shall also love the stranger or resident alien for you too were strangers in the land of Egypt” I get that. But we have to distinguish migrants, we have to distinguish political refugees, and refugees from wars on the one hand from economic migrants, on the other who are in search of a better life. My view is as a rule, economic migrants should be returned home. Why is that?

In brief, because if illegal economic migrants aren’t returned home, then the law restricting immigration is a dead letter, doesn’t matter, in effect you have open borders whoever wants to come can come. That might be okay but sometimes large-scale immigration in a short period of time can be very socially disruptive and disturbing and can create conflict. What’s more, it creates a lucrative market for gangsters to exploit, and it also often can rob the sending country, the home country, of talent. So for example right now you’ll be aware of the migration of hundreds of thousands or millions of Syrians from war-torn Syria mostly into Europe, well right now well I say right now, I mean three years ago when I got this statistic, 40 of all Syrians with graduate degrees now live in Germany. For Syria’s future, that’s very bad. All I’m saying is large-scale economic migration can be a different several different kinds of problem. Now migrants whether they’re illegal will often have paid a lot of money and taken extraordinary risks to get from Syria to Europe and then on to the shores of my own country Britain. And to return them home will be extraordinarily distressing, but is there a better way, does there have to be a better way? I can’t see it.

Those of us who are not involved in government, we can wring our hands and agonize, and agonizing is appropriate. But unlike us, people in government have to stop bringing hands and make a decision, they have to grasp the nettle. And although I’ve never been in government I’m an academic so I’m one of those who has chosen a career path that systematically avoids hard decisions, I get to reflect and spectate much safer, but I’ve always had a deep admiration for those who chose another path and those who have to make the hard decisions and I respect them enormously. So for example, when in a discussion about war a friend of mine mentioned the phrase which you’re familiar with “the war machine” the war machine I said Kian, when you say war machine I see the faces of friends of mine in the military in government who are quite as morally sensitive as you are probably, even more morally conscientious, and they’re in the front line and you’re not, so let’s stop talking about the war machine, let’s talk about with individuals not very different from us in positions so that you and I are by choice of profession, nicely safe from.

So, my main point in this this first of three points is to say that Christians who really care, Christians whose love is serious, need to stop ringing their hands at a certain point and start grasping nettles. We need to get down and dirty just as God did in coming down from heaven

and taking on human flesh, not counting equality with God a thing to be grasped to quote the epistle to the Philippians, I think, taking on human flesh with all its limitations and its tensions and its vulnerabilities in Jesus Christ. So, if you want a theological basis for metal grasping take the incarnation. I should say that I have prepared a handout for this talk that we’ll give you the text of a couple of quotations I’m going to read out to you, if you want such a thing mark will be very kind to give it to you, just let him know. So that’s my first point about the moral duty to grasp metals and on the part of some people and the moral duty in the part of the rest of us to respect the need to do that even if we ourselves don’t do it.

So, now on to Christian just war thinking and a very brief tour. Jesus and his disciples came from the wrong side of the tracks, they weren’t they didn’t belong to the class of rulers, they belonged to the class of ruled, they were not part of the elite. And therefore, for Jesus and his disciples the kind of metal grasping required of those with public responsibility was not required of them or of most early Christians. But in the 4th century a.d Christianity became tolerated in the roman empire and eventually became the reigning or established religion. And in the early 5th century the early 400s we find the famous saint Augustine bishop of hippo in north Africa. In the late roman empire, bishops weren’t just pastors they also had a role as judges. So, they had a role in civil government too and I don’t know exactly what kind of cases bishops would decide but they were in the role of judges and had to decide cases and presumably declare sentences. To his credit Augustine had to be dragged to become a bishop, he did not want to become a bishop but he was dragged into it, and he was dragged into the business of making hard public decisions, including that of being a judge. And in the year 408 he wrote a letter to someone called Paulinus of Nola and he wrote this “on the subject of punishing or refraining from punishment what am I to say? It is our desire that when we decide whether or not to punish people, in either case it should contribute wholly to their security, these are indeed deep and obscure matters. What limit ought to be set to punishment, with regard to both the nature and extent of guilt and also the strength of spirit the wrongdoers possess? What ought each one to suffer? What do we do then when as often happens punishing someone will lead to his will lead to his destruction, but leaving him unpunished will lead to someone else being destroyed? What trembling? What darkness?” and he quotes psalm 55 “trembling and fear have come upon me and darkness has covered me and I said who will give me wings like a dove for then I will fly away and be at rest.” I first read that passage as an undergraduate student of history in 1976 and it marked the rest of my life I think, looking back, I still have the essay I wrote where I quoted it. because what so struck me and what led me to admire Augustine so much was that he did not fly away, he wanted to but he didn’t. I can’t tell you how much I admire that. So a little later, about three years later, Augustine was in pastoral correspondence with Christian military tribunes who were as in those days there was no police there was just the military, the military trivia’s were responsible for keeping law and order sometimes by using lethal force. And in a letter to one of these people called Flavius Marcellinus in year 411 or 412, Augustine is responding to Marcelino’s question about how is it, how can a Christian in the light of the gospel and of Jesus injunctions to forgive and pause and junction not to retaliate how can a Christian hold public responsibility? Because I’ve got to keep law and order and I can’t do it by sweet reason, sometimes I have to use the sword.

So Augustine in responding made a really important move in terms of Christian thinking, and it’s not a move everyone agree everyone agrees with but a very important move. Reflecting on romans 12:17 he wrote “for what is it for what is it, not to return evil for evil as to say what does Paul mean by that? What is it except to shrink from a passion for revenge, for people often to be helped against their will by being punished with a sort of kind harshness, what we might call tough love?” now the important move here is Augustine says “what is morally crucial is the motive of intention not the act” so one can do physical harm, one can even kill, until we know the motive of the intention, we don’t know whether that was right or wrong.

So, for him the rule governing the use of physical force even lethal force for Christians is doing it out of vengeance is forbidden, but if you’re not vindictive, depending on other circumstances, it may be permitted. Telling a very long story very short, Augustine stands at the head of just about at the head of the Christian tradition of thinking about the Christian responsible moral use of force back in the early 400s and since then the tradition has continued to develop famously in the 13th century Thomas Aquinas, systematized mainly Augustine’s thoughts on these matters and then in the 16th century you have scholastic Spanish theologians like Francisco de Vitória and Francesco Suarez, in the 17th century you’ve got Hugo Grotius the Dutch protestant lawyer, since the end of the second world war um just war thinking was revived by the American protestant theologian Paul Ramsey and continues to be developed by people like my predecessor in oxford or Donovan myself and Mark and Dan on my left there. And this is an attempt to think through how Christians can grasp nettles, really difficult nettles Christianly and remain Christians. So let me give you a quick introduction to some of the criteria that the just war dilution has developed. I’m running out of time so I’ll go quickly, first of all there are two sets of criteria. One for governing decisions about going to war, one for governing decisions when you’re in war, I won’t go through them all but three of the most important ones for governing decisions to go to war are just. First of all is just cause and here just cause four is always ways in the Christian view a grave injustice that needs rectifying. It’s not primarily self-defense, it’s a grave injustice that needs rectifying. Now we can talk about when is an injustice grave enough, that’s so that’s open for discussion, but the rule is that a grave injustice that needs rectifying. Following that is the requirement of right intention because you know it might be that you’re suffering a grave injustice from your neighbor there, and I intervene just cause, yes but I’m not intervening because I care about the injustice. I’m intervening because I care about the oil under your feet right. So just cause is not enough the intention has to be to rectify the injustice and then because we all know that war is enormously destructive and hazardous when you start it lord knows when it will finish it needs to be a last resort that’s to say if you search high and low for non-belligerent peaceful means to resolve this conflict to rectify the grave injustice, and only if you cannot find alternative means is the resort to war permitted. Moving from decisions about going to war, decisions about waging or at least to criteria governing the waging of war there are two principles there to criteria one is proportionality that can mean do you think in the waging of war in this particular military operation you’re going to achieve more good than evil is it worth it, that’s one way of understanding proportionality. Which I think on the whole is problematic another way is to say simply are the military means you’re choosing strictly proportioned or ordered or necessary for the end you’re trying to achieve we can talk more about that later if you want. The other main criterion for governing the waging of war is discrimination that’s to say you should discriminate between competence and non-confidence and you should not intend to kill non-combatants, because the aim of war is to stop the unjust enemy from fighting, and you do that by addressing what you do to competence not non-competence. That isn’t to say sometimes in intending to stop confidence you may risk killing non-confidence, but that’s a complication we can discuss later. Let me make clear that just war, the concept of a just war is not the concept of a holy war, it is a concept of a war that all things considered as morally justified. All wars like all human enterprises including churches are morally flawed, we’re all sinners, and you can be sure in the under the pressures of war that grave sins will be committed. So, for example let me assume that most of you like most of my own countrymen think that the war against Hitler was the right thing to wage, okay? Well in 1941, I guess before Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt was privately trying to persuade the American people to enter the war along with Britain against Nazi Germany and there was an incident where a U.S. navy ship came into contact with a German submarine and it was sold to the American people as an act of aggression by the Nazis, the evidence is that it was nothing of the sort, and the president Roosevelt knew it. Another thing that President Roosevelt used to try and persuade the American people was a secret map showing Nazi designs on Latin America which would be a threat of course to America, the evidence is that this secret map was composed by the British intelligence and the Roosevelt knew it. So, there was a measure of deception in Roosevelt’s lobbying the American people to come into the second world war, does that mean that America shouldn’t of fought? Probably not, right so even in spite of that flaw, and many others we might still consider the enterprise to have been justified all things considered.

Now finally some thoughts on national interest. I think I’m probably out of time so I’ll make this quite brief – he says push on, okay. Right so I said that that in just war thinking was justified if it’s to rectify a gross injustice, a grave injustice, so in a sense one way or another all justified wars about humanitarian intervention and we’ve seen especially my own country, to a lesser degree has been involved in Iraq and Afghanistan and whatever you think about the rights and wrongs of that and in both cases there were humanitarian justifications. The fact of the matter is that for U.S. and British intervention to be justified to the American British people, some appeals and national interest had to be made, because it is entirely legitimate for Americans and British people to say well it’s terrible that grave injustice is happening over there, it’d be good if someone would sort it out, but why should our sons and daughters in uniform or our brothers and sisters, why should they be put in harm’s way to sort that problem out there because we can’t do it everywhere. Okay so and the answer has to come in terms of well our national interest is engaged here somewhere, and I want to propose to you that not all national interest is selfish. Not all, I’d actually want to argue that not all self-interest is selfish, that we have a duty to pursue legitimate self-interests and as nations, we have a duty to pursue legitimate national self-interests. As the French political philosopher, Yves Simon wrote during the Abyssinian crisis of 1935, “what should we think truly about a government that would leave out of its preoccupations the interests of the nation it governs.” So I don’t think national self-interest need be immoral and to sustain war particularly war that is not immediately involved in self-defense, it has to be national interest has to be engaged. To end with an example, you may have heard of Edmund Burke the Irish born MP who was very supportive of the American colonists during your war of independence, shortly afterwards in the 1790s he was lobbying for the British government to intervene militarily in Paris because of the terroristic momentum of the revolution in France, and critics said well you know if you want us to intervene in Paris why should we intervene against the barbary corsairs in north Africa? The barbary corsairs were enclaves of pirates in north Africa who harassed shipping and indeed I think in the 1790s the U.S. Treasury spent one-fifth of the total government revenue on buying off the barbary corsairs. So these people were saying to Burke if Paris, why not Algiers? And Burke responded Algiers is not near, Algiers is not powerful, Algiers is not our neighbor, Algiers is not infectious. When I find Algiers transferred to Kelly, I’ll tell you what I think that’s to say whereas revolution in Paris did engage British national interest, north African-based piracy, however regrettable, did not so I’ll leave you there with those thoughts.

[Applause]

Mark LiVecche: Thank you Nigel. Just to give you a heads up how this is going to run, Dan and I will have remarks to follow probably about 10 minutes each mostly to focus on this question of nettle grasping. But for now, rather than just move into another bevy of stuff, if there are questions for Nigel, please ask them now. We might not get through all of them, at some point I might interpose myself, give my remarks to set up further conversation. Feel free.

Questioner: Thank you very much I’m Dan, I’m from New York. I was really interested in how you define economic migrant and since somuch of U.S. history is people who’ve come for economic reasons how do you separate between economic migrant and someone in genuine need and I’m thinking particularly of the Irish potato famine where there were some economic policies that really caused massive immigration to the U.S. and you see the present day we look at Haiti just to our south which based on many circumstances mostly economic you have dire need and many immigrants who want to come.

Nigel Biggar: That’s a good point so you’re right you on the one hand you have political asylum seekers you have people fleeing civil war or filled states so those cases of dire need it seems to me one has to help as best one can I mean the different ways of helping of course so for example the European union and Britain spends a lot of money. Trying to stabilize states in Africa and along the shores of the Mediterranean. But I suppose on the one hand you’ve got people and I need you’ve got other people who are just desperate for a better life and I grant you it’s not really easy to distinguish between them and I guess one has to develop a set of criteria for doing that. All I’m saying is that open borders cannot be the answer because we know what happens when they are and societies are overwhelmed by hundreds of thousands and millions of migrants. I mean that’s what happened to native peoples in north America so open borders can be a problem but I guess one has to judge from case to case and different nations at different times are capable of absorbing more or less and are therefore capable of being more or less generous. But even then, difficult decisions will have to be made and I think my bottom line is we cannot make ourselves responsible for everyone’s fate, we just don’t have the power to do that. And my summoner also said that compassion is good but compassion has to look in more than one direction right so compassion for the migrant clearly driven by something very strong to take all those risks and peel that money but compassion for the working class in my own country as a middle class person for me migrants meansinteresting restaurants, polite baristas, and cheap home help if I can caricature. But for working class in my country can it can mean competition for jobs competition for housing and it has also given British employers a reason not to invest in the training of British unemployed because they can get cheap migrants from overseas so the second thing is let’s have a little compassion for the people already at the bottom of our society when immigration is more of a problem than it is for us and then let’s also have some compassion for the poor people in government to make these decisions but that that take your point it that the distinction between kinds of migrant needs a lot of thinking and probably in different situations one can be more or less generous thank you.

Questioner: I’m Christopher from the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and you gave a very interesting intellectual history of the Joshua tradition and I noticed that many of the figures engaged were incidentally found this could also be an intellectual history of the natural law tradition and ethics so I was wondering to what extent do you think the natural law and just war run together and do you think just war finds its best home in that system of ethics?

Nigel Biggar: Okay, well I mean since Thomas Aquinas and in the Catholic Tradition and the Roman Catholic tradition, yes they do run together historically. Of course Senator Gustin doesn’t talk to his natural law much at all but then having said that there have been protestant just warriors, groceries most famously and then Paul Rems in Oliver Donovan who don’t really think in terms of natural law much so now I don’t think the two traditions of thinking are conceptually sort of wedded whether just war theory has an easier home or a happier home a morenatural home and just in natural thinking I don’t know, I mean joker peace probably commented on that probably will and due course.

Questioner: I was just wondering what you’ve described about the just war tradition and what I’ve read about the rules that are laid out about what makes a just war I’ve always just been curious those can easily be applied to other countries or perhaps we say our enemies they can use those same reasons to validate wars against us so what makes it different from our side and is there somewhat of a sense of Christian just war theory that God is somehow ordaining our version of war and our reasons for going to war? Thank you.

Nigel Biggar: Thank you, yes, everyone can use moral justifications for war and everyone does. You won’t find the Chinese CommunistParty using the criteria of just war thinking which grew up in the Latin west. So that’s the moral system that we inhabit and to some extent it’s the moral system that expresses itself in in the law in the international laws of war but you’re right on both sides of recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and whatever you will find just four series theorists people using just for thinking to argue opposite cases right so just war theory doesn’t give you the answer but it does give you a set of intellectual tools to begin working out an answer and the fact that you get different people using the same tools to make opposite cases does not mean the cases are of equal strength. There might be, but even bad people like to justify what they do morally, so there’s no stopping that. But I suppose as Christians if you’re thinking self-consciously as aChristian you want a set of principles and criteria that seem to you to be Christian so you can make what you think is a decision that’s compatible with your fundamental beliefs.

Questioner: Thanks so much for your talk. My question iswhat would you say to someonewho said or who asked whyshould we as Christianseven get involved inpolicymaking or statecraftwhen there are so many messy choicesinvolved in that such as deportingmigrants or you know killing civilians in conflict, yeah, why shouldn’t we just live peaceful and quiet lives and not even join that sphere?

Nigel Biggar: Okay, did you all heat that question in the back? Yes. Okay so the question was really why should Christians get involved in themessy and morally hazardous business of government why can’t we just live peaceful lives? My answer that is twofold, first of all since we do live in a world of sin you will only get to live your peaceful life in an ordinary society and to be ordered other people’s propensities to do you wrong have to be curbed and insofar as it seems that not everyone can be persuaded by sweet reason not to do you wrong force will have to be used in other words you get to live your peaceful life because other people are having to use force. And then the question is my second point the question arises as to if they have to get their hands messy, why don’t you would be my second point I think there’s, I mean there are different political views I mean some people think that if there were more Christian communities that foresaw violence that the world that that would infect the world and that the world would become more peaceful, I don’t think that’s the case myself. Sure, thank you.

Mark LiVecche: So fantastic, that is an excellent transition to what I want to do. You can hear me in the back I assume? Thumbs up, all right I’m going to act sort of as a bridge between this conversation that was started about grasping nettles and what Dan Strand is going to bring to us a sort of a solution to some of the hazards of grasping nettles. So even among those who advocate in the Christian community the grasping of nettles there are different ways of viewing this. One of those different ways comes out of Reinhold Niebuhr and I’m not going to say much about him because Colin Dueck who I don’t know if he’s here yet will be speaking about him later. But what I want to say right now is first of all we owe a debt of gratitude to Reinhold Niebuhr, if he didn’t exist, we wouldn’t be here. Why? Because we named or started providence magazine in part out of the inspiration of Reinhold Niebuhr and sort of a part of his brand of what we’ve what has been called Christian Realism. But Niebuhr is problematic and I’m going to illustrate why he’s problematic, and then Dan is going to give us the solution to his problem. Niebuhr the debt we owe to him is that Niebuhr almost alone in the build up to World War II worked to try to encourage the mainline church to support American intervention against Hitler. When the Japanese zeroes dropped out of the skies over pearl harbor he wrote an essay called Our Responsibility in 1942, and there he basically said finally, now we have probably been provoked out of our obsession with self-interest and will now be more willing to enlarge the scope and to be concerned about the interests of the wider world community. And it was an important insight. The way he phrased this is we have been thrown into a community of responsibility

because we have been overcome by a community of sorrows or something to this effect. So, this idea of responsibility plays large in the Niebuhrian Universe, but it comes at a cost. Why? Because for Niebuhr, build up to World War II finally sort of disabused him of his undulating relationship with passivism, so in the build-up to world war one Niebuhr was a pacifist – he sees the behavior of the Kaiser and the German people, he’s bothered by this, he argues for American intervention world war one is won I’ll put that in scare quotes we can talk about that later. After world war one, he looks to a friend and he says I’m done with the war business. In the build up to World War II he begins to push for American intervention and I think after world war ii he was finally no longer in support of pacifism. But that that comes with a qualifier Niebuhr was always a pacifist he simply became a pacifist willing to kill what do I mean by this he believed that the number one law incumbent upon Christians is what he called the law of love, and love wasn’t simply non-violence, love was non-resistance to evil, and we could have a fascinating conversation about all the different things that neighbor thought was categorized under this idea of non-resistance coercion, bad feeling, all sorts of things, non-resistance to evo is the rule. The problem with this is there’s a competing rule or competing law and that’s for responsibility Niebuhr recognizes that there are times where Christians have to grasp nettles, or as he put it dirty their hands in

order to help the world avoid calamity, absolutely catastrophic calamities.

So, there’s this competing law of love which is non-resistance if you pursue that you’re not going to get any responsibility because you’re going to be too busy trying to be loving, but because this world won’t agree with your choice to try to be loving and the enemy always has a vote, you’re probably not going to get a lot of love either, so that’s impractical and we don’t do that. We pursue responsibility instead in which we can get an approximation of responsibilities met and we can season it or qualify it by love. So, you pursue love you’ll get another level of responsibility if you pursue responsibility you can get a measure of both, it’s the best we can do, our hands have been dirtied but we can’t move this through this world without incurring guilt. All right this idea of not being able to move through the world responsibly without incurring guilt is going to be important I’ll explain why in moment. All this can be boiled down to this idea that killing is wrong but in a just war is necessary. And if you’ve read any of my stuff I’m obsessed with this idea and you can find this locution in various war memoirs if you look for it killing is wrong but in war it is necessary I’ve written before on timothy kudo who was an American marine lieutenant deployed to Afghanistan and he has written a series of op-eds in New York times talking rather poignantly about his own experience with killing, and he’s careful to point out, he says I was never the trigger man I never directly killed anybody, but I called in artillery strikes, I gave permission to snipers to shoot on people and planting IEDs, and the like he found himself in the kill chain and that has haunted him. A caveat, well what he says is this, before we get to the caveat he says war fighters enter into war growing up as good Americans knowing that the rule is thou shalt not kill, but we enter into military service where very quickly we recognize that the metric for success is killing, and he said and to be able to move from the one to the other is you know is a kind of catastrophic or an incomprehensible transition right and it comes at a cost, and the cost is recalibrating your moral compass, and so that he no longer believes he was the good person he thought he was before he went to war. The caveat is this, Timothy Kudo has a sort of a bad kill in his history he was partly responsible for the killing of two unarmed Afghan teenagers and it was an accident, they had come two kids on a motorbike they were coming from a hill so a position of tactical superiority if they met they were aggressive they tried to get the kids to stop, they wouldn’t stop, they went through their pre-assigned protocol the motorcycle kept going on at the last moment they thought they saw rifles, and then the sun colluded with the confusion to shine off the chrome on the motorbike, and it gave the appearance of muzzle flashes so the marines opened fire they killed the kids they were unarmed and this still haunts Kudo. What I want to stress though is that it’s not simply a bad kill that taints a warfighter’s views about killing. So you could read William Manchester’s Magnificent Darkness Afternoon I think that’s during the title somehow but Darkness At Noon, I think and the introduction to this book is called the blood that never dried and in there he talks about his first kill, and he kills a Japanese sniper who is decimating his men and he single-handedly breaks into a building breaks into the sniper’s hide you know this extraordinarily heroic moment he kills the sniper at close range, it’s a bad shot he hits him in the thigh the sniper is bleeding out and he’s face to face with this man’s you know sort of dying humanity and he crumples to the ground and William Manchester describes you know as he’s dying he’s gasping for breath, he’s twitching, he’s farting, he just describes the sheer tragic humanity of this moment and fairly intimate moment, and then Manchester turns to himself and he says and I realized I was blubbering, I was twitching, I vomit over myself, I urinated my khakis, right and this is his response to killing. And in some ways the rest of the memoir is him seeking absolution and any of us who have worked I think to any degree, I mean most especially Chaplain Mallard who spoke to us yesterday knows that very often people who redeploy out of a war zone are looking they want to talk they want to confess the things they’ve done, they’re looking for absolution and forgiveness, and there are occasions where both absolution forgiveness are appropriate. But one thing that I have come to insist is also appropriate is that there are many times where these guys don’t need forgiveness, they need vindication, you forgive somebody who’s done something wrong and repented, you vindicate somebody who has been found clear of any wrongdoing whatsoever, and there is a place within Christian intelligence that says killing comes in different kinds it’s not just Christian intelligence, it’s common law and common sense, some kinds of killing you never do we call it murder, it’s the end of that conversation, other kinds of killing are accidental – that’s killing of these Afghan teenagers, there may be varying degrees of probability maybe you should have been more careful etc, but it’s essentially morally neutral there’s another kind of killing, the just war tradition argues that is morally permitted and maybe and we could talk about it even morally obligatory so there’s all of that. Now what I don’t want to do is to shrug all this away and say killing should be an easy enterprise you know good Christian boys and increasingly good Christian women should be able to go into the combat zone and kill you know a lawful enemy with impunity I don’t want to suggest that I so don’t want to suggest that I wrote a whole book about not suggesting that right so I called it the good kill just foreign moral injury and one of the observations there is that killing should always weigh heavily on the soul. But here’s the problem, most of us are familiar with post-traumatic stress disorder which comes from a life threat trauma usually reacts and the manifestations are paranoia hyper vigilance and the like there’s a new proposed sort of subset of post-traumatic stress disorder called moral injury. There’s a couple different definitions the definition that I use in the book is a moral injury occurs when you do or allow to be done something that goes against a deeply held moral conviction va clinician work has drawn a strong line between having killed in combat no matter what the kill accidental, lawful, whatever, having killed in combat is the number one predictor for combat veteran moral injury. Moral injury is the number one predictor for combat veteran suicide, so there is a strong line that can be made between having killed in combat and then killing yourself. Killing is wrong says Niebuhr, but in war it is necessary Niebuhr is made the very business of war fighting morally injurious and that is a calamity on our military men and women. I draw a distinction in the book between moral injury moral bruising a bruise is a combat or an impact trauma it’s on the surface it hurts but it’s not debilitating to the level of an injury. I think war should be morally bruising, Augustine talked about the sorrows of combat that any sensitive soul should feel that if you don’t feel it that’s the real tragedy of war. So, a space for moral bruising, by pushing against moral injury where you’ve done nothing wrong, some warfighters deserve a moral injury, many do not. Niebuhr doesn’t get us out of that, Niebuhr has made the very business of grasping nettles morally injurious and so I asked myself who will rid us of this cursed priest and when, the good news somebody will. All right, all right Dan’s going to speak and then we’ll take questions for everybody.

Daniel Strand: Yeah, so Mark and I are coordinating as you can see talking about Niebuhr and then the person I’m going to talk about who’s Paul Ramsey. Before I speak, I am an employee of Department of Defense in United States Government so what I say here I do in my capacity as a civilian and they do not reflect the views of the American Government necessarily. necessarily I doubt they do, I’m not sure. So, we’re talking about grasping nettles and dirty hands this question of when you are involved in federal government, when you’re involved in many aspects even of American domestic life, my wife is a social worker, so she sees lots of tragedy on a daily basis. When you’re in international politics as we’ve been talking about today, especially when you’re in the war making or defense business, all the problems that you deal with are essentially have potential or are in fact dirty hands type problems. They are what are often referred to as wicked problems. Right, they’re complex, they’re uncertain, there’s no clearly right answers and you know we could talk about Afghanistan during Q&A, I’m not going to talk too long here but anybody who tells you there’s a clearly right answer to Afghanistan is lying to you, right. There are maybe better, and you know and that’s the vigorous discussion that we’ve that people are having publicly and I think it’s a good discussion to have but all of those positions require a level of tragedy, right, people are going to die, violence is going to continue regardless of whether the United States stayed or left. And that’s in so the questions that we’re wrestling with and if any of you who are interested in going in into government or to deal with these sorts of questions in your careers you have to realize those are the questions that you’re going to deal with. I thought the question that was asked earlier by the gentleman from I think Virginia was exactly spot on, right, if you want clear, clean, nice, sort of simple answers which today I think in a lot of our political discourse people sort of imagine that that those things exist – international politics is not for you, defense is not for you because that’s just not reality. I think that’s the point that we’re all making here right. Christian realism which kind of the spirit of Christian realism I think Eric did a great job, but I think every speaker here is carrying forth this kind of, has these sets of convictions is that the world is a rough and messy place and that is what you have to start with the way the world actually is, and then you can deal with it. And what I think Ramsay offers, Paul Ramsey, you know I’ll Segway now to talk about Paul Ramsey Ramsay was a contemporary somewhat of neighbors he was younger at the time he started teaching at Princeton University in the early 1950s. He was a Christian realist, he was friends with Niebuhr different sort of personality most many people have not heard of Paul Ramsey, I mean Niebuhr was a public figure he was interviewed on you know NBC, people wanted to know what Reinhold Niebuhr thought about various issues. So, he was a you know a publicly, he was on the cover of Time Magazine, so he was all over the place, Paul Ramsey was not. But Paul Ramsey was deeply influential in a different way. He trained, he had a lasting influence in terms of training Christian ethicists and as was mentioned he, I won’t say single-handedly because you know obviously people thought about just war prior to Ramsey, but he really was the person who revived the tradition. It was primarily the purview of the catholic church and in a protestant country that probably didn’t count as much, at least at the time. What Ramsey did was he made it, he revived it, and really brought it back into public view and influenced most of the scholarship, you know after the he published two books in the 1960s on unjust war and that really kind of set off a you know a train, and he’s also I mean Ramsey was just a significant figure in many other respects so didn’t have the visibility but was nonetheless extremely influential and important, and I’m going to just say one you know briefly how he contrasts with Niebuhr he wrestled with Niebuhr he considered himself a Christian realist in many respects but he ultimately breaks from Niebuhr on this question that Mark was talking about, this idea of this distinction between responsibility and love. And this sounds kind of like abstract stuff that you know just theologian and ethicists like to ponder but actually it has some really fundamental implications practically speaking so what the simple answer to what Ramsey does I’ll say two things about Ramsey, he and Niebuhr I would argue, so Nigel mentioned Saint Augustine, Augustine is really the kind of the patron saint of both of just war and Christian realism the people who are going to develop ideas on in both traditions are both drawing or at least they find their inspiration from Augustine. And the I would argue that neighboring ramps are kind of touching on different sides of Augustine, because Augustine is if you read his work as luminous, nobody’s ever read all Augustine’s work okay just like when somebody says they’ve read all Thomas Aquinas no they didn’t, but Augustine I mean he wrote you know book bookshelves full of he would just wake up and dictate all day long he had numerous scribes he was just he was he was a genius. But two of the big themes in Augustine’s work two things that kind of mark him off was this, his emphasis on love, prior to Augustine I mean you’d think wow you know that that’s nothing profound. Christianity, it’s always been this kind of the love commandment but what Augustine did was make it clear how love and also engaging in much of this sort of philosophical Greek and in Roman tradition at the time which Christians oftentimes did not engage in. Augustine they often say sort of baptized classical thought. But what he did most profoundly is deepen drawing upon figures like Plato Neoplatonism at the time, deepen and extend our understanding of love, and Augustine makes this statement he says the “love is the form of the virtue” so love is the ultimate norm for guiding all of life, right we don’t cordon off love into just one section and then we set love aside and we go do you know the messy stuff of public life now he says he’s insistent that love is the ultimate guiding norm and that is what Ramsay is doing in his work. And so Ramsay captures that side of Augustine and really insists on the ultimate norm of love, that love is relevant to all of life and it has to be relevant even to social policy, even to politics even to these sorts of dirty hands questions, that sounds very foreign to our thinking right we think how can these how can these rough often you know messy and oftentimes just Syria as Nigel mentioned I mean if you really start looking into what’s going on in Syria even today it’s absolutely depressing. Hundreds of thousands of people have died. You look at, we’re living through a sort of period of mass immigration around the world right, displacement of people moving, fleeing the Rohingya, in Myanmar, right there’s just there we could go on and on with the sort of the veil of tears in which we live in this world and in many respects, we’re safely corned off from that. But if we really think about what’s going on in the world it’s tragic right. But Ramsay insists, he insists this is his kind of core conviction and we can talk about this in the Q & A, he insists that love can take many forms, and so this is where he resolves this sort of responsibility versus love tension that you see in Reinhold Niebuhr he says to act responsibly is loving. Now it doesn’t mean you can sort of baptize everything that you do and claim well I’m acting responsibly so I can do whatever I want, no that’s not the case. But to engage in say warfare, which is a bruising and bloody and anybody who’s been a part of it does not speak whimsically of war, but that can be an act of love. Ramsay himself it becomes a key figure in arguing for a moral basis for deterrence. Nuclear weapons right, using nuclear weapons, this seems how can this be, how can you say it’s loving to you know use and Ramsey’s position is controversial too, right. So, it’s just because you say I’m arguing and I’m thinking about love and trying to apply to policy doesn’t mean that it’s necessarily going to be the case. He also argued in favor of Vietnam, a lot of us would probably disagree with his position on Vietnam, but he comes at it with a conviction that the rough justice the rough love that’s required in politics is, that’s a form of love, that statecraft can be a form of love. Now not sentimental right, you can’t have this rosy view of the way the world is you can’t have a rosy view, or an optimistic view of the way human nature goes or you’ll become disillusioned, right. It’s just not possible to operate in those spaces unless you have a realistic appraisal of human beings, of our motives of the way we behave as collectives often in terrible ways. But Ramsay insists what the Christian’s obligation is to enter those spaces and the second point I want to make, Niebuhr really captures well the side of Augustine that emphasizes original sin, the fallenness of human nature and pride. So, Ramsey and Niebuhr I think are two figures to hold together very well. And Mark Tooley passed along a paper a couple days ago on this debate over Vietnam, Ramsey and Niebuhr took different sides of that debate. It’s interesting to see Niebuhr’s position really comes from his deep skepticism about these sorts of adventures abroad, right. So and that comes from his skepticism about what humans can accomplish, he’s restrained, he’s sober, he worries about American pride, he worries about the power that America was given post World War II that was his number one concern, he said we have to restrain this the super goliath that you know we won the war America’s triumphant the feeling of America at that time was just this overweening sense of a sort of you know they felt America had sort of arrived at that moment, and Niebuhr worried about that deeply. So, you can see that sort of healthy tension there between someone like Ramsey who wants to insist on love, intends to perhaps justify things that in the name of love, that may need more sobriety, more restraint, that someone like Niebuhr cautions against. But lastly the point I want, last point I’ll make about Ramsey is he demonstrates the complexity and the challenge of getting at these thorny quests, these thorny problems that you face in international politics. If you read his book the just war tradition which is considered to be his classic it is a struggle, okay anybody who’s looking for like an easy read you will you know the opening after the opening few chapters your eyes will begin to glaze over. The point I want to make about Ramsey’s kind of depth is that he was a wrestler and what I mean by that is he had this phrase the “knobbly height of reality” for him reality was complex, complicated, hard to get at but the job of the Christian policy maker, politician, whatever sort of venue you find yourself in public life is to wrestle into struggle and to appreciate the complexity of it and have the time and patience to sort of work through it and describe patiently and find out all the different dimensions that are going on because only after that wrestling that you can you know arrive at a conclusion bringing alongside this notion of love. You can’t just say love is this policy here simply, you have to wrestle with that complexity. So, with that we’re going to open up the questions.

[Applause]

Mark LiVecche: I’m going to make one very brief comment and then let Nigel make a couple of comments my brief comment is this if you want to appear on the cover of Time Magazine write like Niebuhr, don’t write like Paul Ramsey. That’s my comment. Nigel is going to give a few comments and I hope just to chum the waters a bit you might touch on the difference between moral and non-moral evil and why I might ask that question.

Nigel Biggar: That was exactly what I was going to do. Just a couple of thoughts, first of all Mark gave us cases of people who were found killing extremely psychologically disturbing right and it just struck me that agonizing over killing is something Christians should do, but if we in our societies do that it’s probably because we’ve been Christianized. I’m aware that there are societies where killing is not such a problem. So, I was reading recently about Somaliland in Africa in the 1940s, where the author was living among African tribesmen whose raison d’etre was to be warriors and killing the enemy was not something to regret, it was something to rejoice over. So, don’t assume that everyone finds killing quite as dramatic as a westernized, Christianized person would do. But maybe because of our being Christian but even those of us who are called to kill, nevertheless agonize over it as we should. That’s my first point. Second is directly to well the second point was just remind youthat we’re going down deep into just war stuff because it’s an illustration of Christian wrestling with a general problem of metal grasping. There are other nettles to be grasped over immigration of all sorts of policy but this is, this war is obviously one of the most difficult and sharpest of metals. So my third final one is this, the general issue has to do with there are sometimes not infrequent when if we want to achieve good or do good we cannot avoid doing harm. You might say if you want to do good, you can’t avoid

doing evil, and if you’re a Lutheran you’ll say you can’t do right without doing wrong. I’m not a Lutheran, I find that confusing. I go with Jericho peace’s church even though I’m not a catholic, I prefer to talk about pursuing the good though, even though I have to do non-moral evil. Evil here means damage, so I cannot save you without killing you, my aim is the good of saving the

innocent but in so doing I have to cause the evil of killing him. But cause it’s not immoral to do it, my act is right, it’s morally right that I have to cause no moral evil or if you like damage

that’s the dilemma I think we are grappling with in general.

Mark LiVecche: And would you say a Christian shouldever do moral evil?

Nigel Biggar: In order to all wrong but well, no I wouldn’t. I don’t think, no uh but

the question of what is morally wrong is often a very contentious one, correct.

Mark LiVecche: All right we have a few minutes forquestions, comments, rebukes. Feel free to come up to the microphoneplease and you can even just come andform a line, it’s not like thefront of an airplane sofeel free to assemble.

Questioner: My name is Ethan from Wheaton College. I think I forget your name in the

Middle, but you said the metric for success is killing. Could you explain that a little more?

The metric for success is killing in war.

Mark LiVecche: All right I don’t know if that was twoquestions. My name is Mark LiVecche. Thesecond question, yeah, my metrics for success just for clarification if this is necessary is

not killing. Timothy Kudo talking about the paradox and I don’t know that he knows and I suspect he doesn’t but there’s an liberian paradox killing is wrong but in war is necessary right responsibility is right or love is right but you know responsibility is required. So paradoxes, for Timothy Kudo all I wanted to say is that he believes that the rule, the moral rule incumbent upon

human beings is thou shalt not kill, making no distinction between killing and murder, but the confusing piece for him is that when he goes into combat he realizes that in order to bring this war to a successful conclusion, I probably have to kill my enemy and that for him was morally disequilibrating, right. It knocked his crutch out, he couldn’t understand how I’m supposed to

do what is wrong and for that to be somehow okay, and just that’s all he is phrasing for that was the metrics for success and war is killing.

Nigel Biggar: But I agree with you, Ethan. I thinkas just war, I think the metric forsuccess is not killing the metric forsuccess is breaking the enemy’s will tofight nowin immediate circumstances, killing numbers of the enemy might be aproxy for that but that’s not the point.

The point is to break if the enemy surrender you’ve won. Killing is something you have to

do to get them to stop fighting right.

Mark LiVecche: That’s a good point. That’s a goodpoint. Let’s let our Marine defend the Marines.

Speaker: Talking about a lieutenant, a platoon commander his fight is avery different fight from

what we’re talking at a strategic just war level. So at that point of conflict for him to kill him

probably more often than not he is the metric of success. Sure, but the most outward obvious

example.

Daniel Strand: That’s really helpful, your level of analysis if you’re talking, you know in the moment when you’re at, the clash of you know the point of thegun then yeah. I mean that’s that’s right.

Questioner: Hi I’m Katherine, I’m from Liberty University thanks for coming to speak

with us. So you guys talked about justice before war and just war theory and war but I was curious as to what your approaches would be to just post bellum?

Mark LiVecche: If just war theory could be set uplike windows on a computer screen youwould click on use ad bellum a windowwould drop down you would click on rightintent another window would drop downand under there you would find use postbellum because the end of a successfulwar ought to be peaceand then you would have to drill down asto what peace in this particularcircumstance looks like it might not beoutright victory, outright surrender, itmight be getting Assad to stop gassing his people right. So it’s found under the right intentclause. Eric Patterson if he were here he would say it should be a codified third category within it I’m just afraid if we keep adding to the category we’re going to end up with you know use antebellum and all sorts of crazy things, we should absolutely be cognizant of what we’re looking for because that’s the end we want to achieve and that will dictate everything from strategy to tactics so it’s an important, no longer overlooked, it’s an important element of just word tradition.I don’t really push for it becoming the third category.

Nigel Biggar: The reason people dopush for it to become a separatecategory is our experience in Iraq wherethere was a signal failure to thinkabout what happens afterwards. But, I agree with Mark conceptually it’s thereand it’s already there in the system.Peace is the is the end if it’s just war,you need to think aboutwhat peace would look like because thekind of war you fight has to achievethat kind of peace.

Mark LiVecche: And just a caveat that’s going to makeJoe Capizzi a little crazy but youcan’t always predict what that’s goingto be. I make an argument thatdropping the bomb on Hiroshima led tothe kind of peace we now enjoy with the Japanese, so it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to do you know lesser harms in that sense it might look very different depending on the situation.

Questioner: Hi, I’m Greg Wiggle from the Universityof Dallas. I just want to start with

thank you, guys, for coming down here and talking. So, a question that’s been on my mind that kind of relates to Christian realism and a lot to this conference in general. It’s actually two questions so the first I wanted to ask was in a case of foreign policy and we’re approaching it as Christians with a non-Christian country, how is it, what we do in terms of foreign policy. Not come off as what was talked about yesterday as cultural imperialism similar to things that the far-left kind of does, so how do we get them to kind of buy into our ideas as well? And then another question that kind of ties more into just war, could just war be seen as a type of charity?

Nigel Biggar: A type of charity? Yeah.

Daniel Strand: I mean I think we’d all probably say yesto the second question. Okay, yeah. Imean for Thomas and for Augustine andI would imagine I think the Suarez of divatorio if it falls underfor Aquinas, it’s listed under the section in the suman on charity and so it’s addressed as a question of love. That’s the way Augustine primarily dresses as an act of love, Ramsay treats it as an act of love. I guess the question is how that fits with a sort of natural law tradition which the classic tradition grows out of I think Joe or maybe Nigel might have a better grasp on that.

Mark LiVecche: I was just goingto saycase by case right so you can give adefinition of what love looks like,but you have to apply it by cases fromafar. If I don’t know the context if, Idon’t know the intent, if I don’t knowthe motivations, I might see an act overthere in the corner that looks likeassaultbut if it turns out to be a rescue of aninnocent person being unjustly aggressedit’s an act of love, but without thedetails I might not know what it lookslike from afar. So, you look at war from adistance and to call it an act of love seems aparody.You have to knowfor the details.

Nigel Biggar: But on yourother question about culturalimperialism – I suppose my view is that

we have to represent what we think, whoever we are and if we come across another people who don’t think as we are presenting them with what we think is not imperialism it’s just, this is what we think. Now depending on what we want from the other people we may have to negotiate and

compromise. But it’s not necessarily imperialism for us to do that. Just taking the case of the ethics of war, yes the ethics of war as we understand it in the Christian or post-Christian west has a particular tradition of thinking, and no, the Chinese Communist Party probably doesn’t buy into it but if you were to persuade the Chinese Communist Party representative to sit down and look at ancient or medieval confusion thinking about war you’d actually find a lot of similar stuff.

So, you could find common ground that way, without being imperialist.

Questioner: Good morning, thank you all for beinghere. My name is Sean Kim from Wheaton

College. So, my question would be what should the Christian response be if the instance the nation went to war and we perceive it to be as unjust, what should our response be? should it be to submit to the authorities? Or I don’t know like, let go of that nettle? Like what should our response be if that is the case?

Daniel Strand: So, you’re saying you as a citizenare confronted with the fact that yournation is engaged in an unjust war?

Questioner: Yes, as acitizen and maybe Christians who are alreadyin the government and in statecraft whatshould their response beif we do go down that direction?

Nigel Biggar: There’s no doubtChristians areresponsible to God through theirconscience, and if they really become if,you really become convinced this war iswrong, of course you have the democratic rightto protest, if you’re in government or the militaryyou may resign under certaincircumstances. But having said that, I don’t know of a war that wasn’t controversial. Now some may be more obviously wrong than others but thinking about people who are in uniform sometimes it’s very difficult to figure out quite where right lies, and often times one may have good reason to give benefit of doubt to what your leaders say. Certainly in the middle, you’d have to have a very strong reason it had to be very clear indeed in your own mind this was wrong but sometimes they have, I mean famously Francia Stutter the Austrian peasant who was in German uniform refused, and was executed.

Mark LiVecche: Just two quick things I’d sayon that you know I think he took the best route which was atfirst to avoid even entering a uniform and I think there were times where Christians would have to say the nature of my regime is so wrong that I will not represent it: Nazi Germany, apartheidSouth Africa would be two, I don’t think a Christian should enter into military service in those nations. Being in uniform then becomes an even larger problem because I do not believe inselective conscientious objection. I think that would make a hash out of many goods that we have to be able to rely on. I do believe in conscientious objection if you if your principles say no war period you shouldn’t have to fight but selective conscientious objection would be a very different thing mostly because very few people within uniform have anything like omniscience or access to the detailed information be able to make a good choice.

Nigel Biggar: In the military at the momentyou knowno state can depend on a military

where its members might simply decide on private conscience just not to fight that would be chaotic. But presumably, the practice would be if you know, if you’re called to fight a war you don’t believe in you fight it and resign afterwards. Is that the, I don’t know what the practices are?

Mark LiVecche: We’ve got the chaplain giving us a thumbs up.

Nigel Biggar: Okay, okay, that’s the practice.

Daniel Strand: The only thing I would add is Ramsaymakes this point and I think it’s veryapplicable for today, he says when it comes to politics thechurch is a theoretician.And what he means isChristians, Theologians, often clergy often make pronouncements and often those pronouncements are based on limited understanding of the situation, intelligence, and this is hard because in the age of social media we just react immediately right we have these strong moral reactions, we denounce but I mean there’s a level of humility that Christians need to have. Which is the politician, I think Nigel made this point very well, politicians are thrust into a position of great responsibility and the position needs to be trust indifference. I would say that’s the kind of initial position because honestly, we just don’t know everything that they know, they’re privy to information, they understand the complexity, now they’re not perfect they’re not a mission so

they’re still worthy of criticism and they need to be held to account but a lot of times it you just get this sort of pontificating and I’m not saying you’re doing that, but you get it all where people will we’ll talk about the complexity of some of these decisions as if it’s just so obvious right. And I think the council should be more humility restrained, you know I don’t know what they know

so, I think there’s a level of deference.

Nigel Biggar: And exactly the same applies to notgoing to war. Sometimes not going to be war can bewrong. Yeah, thank you, very good, yeah.

Mark LiVecche: Last question, I think.

Questioner: I think this was touched on briefly andI think we can all agree that war should be a last resort, it shouldn’tbe a first option. But could you just elaborate on some of the criteria that

would account for a last resort because you can’t ever truly exhaust all options, but when is it a

reasonable approach to say war is an appropriate last resort?

Nigel Biggar: That’s a good questionI’m not sure whetherI can give a good answer. So let’s take for granted that the issueis a case of grave injustice, let’stake for grantedthat you have tried diplomacy,let’s take for granted you’ve thoughtabout financial and economic sanctions, let’s suppose the other guy the otherpeople still want to negotiate they wantto call another set of negotiations – this is the 13th set of negotiations, the question in your mind then isare these people negotiating in goodfaith,right. How long do you keep on negotiating withHitler given his record? At what pointyou saythis man can’t be trusted, he simply usesnegotiations as a delaying taxi, whatever it turnson the casebut the rule I think is thatwar should bea last resort – all otherrealistic alternatives have beentried. I mean there are all sorts oftheoretical alternatives

but they’re theoretical, they’re not available, that would be my thinking on that great good.

[Applause]

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024