I am the son of conflicting sixteenth-century cultural roots. My mother is descended from Anne Hathaway—no, not the American actress but the wife of English poet and playwright William Shakespeare. My father, a conscientious objector during World War II, is descended from Swiss Anabaptists, the progenitors of the “radical reformation” of the early sixteenth century. What to make of this strange mix?

Confessing my own ignorance of the English poet and playwright’s strict views on war and coercive force, I am—it is safe to say—indebted to a more “catholic” view of Christian faith as it concerns political authority, responsible citizenship, the common good, and wise public policy. Much of this personal formation was the result of a season of doing public-policy research in criminal justice in Washington, DC, before I entered the university classroom. And for this “education” I shall remain eternally grateful.

Behold, it is a pastor of an Anabaptist church in the nation’s capital, Washington City Church of the Brethren on Capitol Hill, whose recent book captures my attention. The title itself—Hauerwas the Peacemaker?—raises ineluctable questions. If this were not enough, the subtitle—Peacebuilding, Race, and Foreign Policy—strikes the reader as maddeningly irresistible. Where to begin is the great challenge.

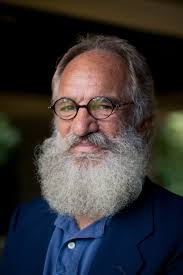

In this volume, Nathan Scot Hosler, who with his wife is co-pastor of WCCOTB, looks to one of the most outspoken pacifist theologians of our time as inspiration for contemporary “peacemaking” and “peacebuilding” efforts. For Hosler, who was “born, raised, and baptized into the Church of the Brethren, one of the historic peace churches” (emphasis his), the person “who follows Jesus cannot participate in war,” since “war has been abolished in Christ.” Hosler finds a special kinship with theologian Stanley Hauerwas, whose unrelenting criticism of “militarism” in American foreign policy undergirded an illustrious career at the University of Notre Dame—alongside Mennonite theologian John Howard Yoder before Yoder’s death in 1997—and at Duke University before his recent retirement.

Although Hauerwas has written relatively little on “peacemaking” (narrowly construed), his commitment to “nonviolence” imbues virtually all of his work—even his response to John Paul II’s 1981 encyclical Laborem Exercens wherein he depicted economics as a “violent” public activity that is scarcely redeemable. Hosler views Hauerwas’ writings on peace and nonviolence—e.g., The Peaceable Kingdom, “Peacemaking: A Virtue of the Church,” War and the American Difference, and “The Nonresistant Church”—as important for developing the implications of “peacemaking” as policy. Most of the book is devoted to considering those possibilities.

At the broader level, Hosler understands three streams of thought to inform “peacemaking” within Christian ethics: the “social Gospel” as advanced by Walter Rauschenbusch; the black church’s experience and liberation theology; and “historic peace church” activity as embodied in the writings of John Howard Yoder. Despite the book’s subtitle, much of Hosler’s book is devoted to this third stream, as evidenced in Hauerwas’ theology, his ecclesiology, and the potential in Hauerwasian social ethics (undeveloped by Hauerwas himself) for the “peacemaking” project.

Most contemporary Anabaptists are reticent to engage their own beginnings, and Hosler is no different. For example, there is no discussion in this book of the Schleitheim Confession of 1527, which formulated Anabaptism’s early commitment to “separation” from “the world” and “nonviolence.” This, it needs remembering, was against the backdrop of the magisterial Reformation. The magisterial reformers held to the conviction that while retribution does not belong to the church, it is not only permitted but commanded of rulers. Thus, two differentiated spheres of authority were understood to coexist in tension. How that tension was navigated differed considerably from Martin Luther to John Calvin and other magisterial reformers; at the same time, a tension was maintained nonetheless.

From virtually the beginning, Anabaptists understood these two spheres to be staunchly oppositional; therefore, a Christian could not be a magistrate or punish with the sword. Among the first generation of Anabaptists, Balthasar Hubmaier (d. 1528) was one of the few who embraced a “Lutheran” view of political authority and Christian citizenship. By the second generation of Anabaptists, embodied chiefly in the “Mennonites,” pacifism was normative. The Reformed-Anabaptist debate in this regard would come to a head in May and June of 1571 at the Frankenthal Disputation. The Reformed position seemed to expose a weak spot in the general Anabaptist/Mennonite argument: if a Christian could not be permitted to serve in any sort of ruling capacity, the implication is that the office qua office is not of God but of the devil and therefore intrinsically evil. A further inconsistency needed clarification, based on Article VI of the Schleitheim Confession: three times in the opening paragraph of this article the confession states that the sword is “ordained.” (1) It is “ordained of God” even when existing “outside the perfection of Christ”; (2) according to the Law, the sword was “ordained” for the purpose of punishment; and (3) the same sword is presently “ordained” and “to be used by the worldly magistrates.”

By the end of the sixteenth century, Anabaptist types would maintain the stark polarity between Christ and “the world,” resulting in an enduring form of separatism and pacifism that, at least in its practical expression, would necessitate a withdrawal from “the world” and be characterized by a narrow sectarianism. Both of these elements, to a measurable extent, remain 500 years later. For example, today one will not find Anabaptists working in certain professions that historically have been thought to mirror the values of “the world”—among these, for example: politics, the military, police work, law enforcement, policy analysis, economics, law, security, banking, and the like. The reasons for this demarcation remain essentially theological.

Yet, even when “separatism” and pacifism remain the theological bedrock of Anabaptists in our day, most Anabaptists chafe under the accusation that they are “separatistic.” This sort of charge particularly angered Hauerwas’ mentor, John Howard Yoder, who was perhaps the most influential Mennonite theologian of the twentieth century. Some have also leveled the charge of sectarianism at Hauerwas, and with good reason. Like Yoder, Hauerwas has also reacted “violently,” arguing that nonviolence is the church’s essence and therefore responsible political ethics.

Historic Christian faith, by contrast, has repudiated the pacifist’s position as normative, despite pacifism’s immense appeal from generation to generation. Historic Christian theology both rejects the misreading of the early church arising from a so-called “Constantinianism”—to which both Yoder and Hauerwas have been beholden—and affirms the divinely ordained nature of political authority in a fallen world, even when that authority is subject to abuse and misuse. Historic Christian faith sides with Cambridge philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe and with C.S. Lewis, a contemporary of Anscombe. In her memorable essay “War and Murder,” Anscombe reminds us that pacifism, if taken literally, makes all of society—indeed, the entire world—unsafe. And Lewis, certainly no political philosopher, challenged the stereotypical pacifist interpretation of the “Sermon on the Mount”: surely our Lord did not mean that we turn another person’s cheek when assaulted. Perhaps the greatest failure of ideological pacifism is that it misinterprets charity. From Augustine to Aquinas to Luther to Hugo Grotius to Reinhold Niebuhr to Paul Ramsey to James Turner Johnson (and before and beyond), it has been argued that Christian love will on occasion call upon us to protect others, inasmuch as they are made in the image of God. And that protection—that defense—will sometimes require force—measured force, but force just the same.

George Orwell, roughly contemporary to Mahatma Gandhi and having served in India himself, admired Gandhi’s character but was supremely critical of his pacifism. The reason for this was quite simple. When European Jews were being led to their slaughter in death camps during the Second World War, Gandhi’s only advice was that they serve as martyrs, not that the nations of the world should protect or deliver them from death. Orwell’s anger, let us admit, was well placed.

Stanley Hauerwas has had a celebrated career as a theological ethicist and as a card-carrying pacifist. I do not begrudge him. Much of his appeal, in many circles, has been his ability to be provocative. But Dolly Parton has also made a career out of being provocative, and I say this as one who happens to live in the state of Tennessee, not far from “Dollyworld” to which venue multitudes of people flock for entertainment:

I personally yearn for the day when Dolly retires from public view.