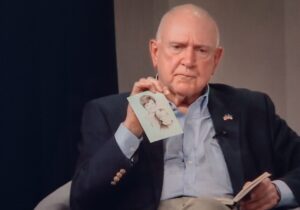

Lewis Sorely, author of A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam, spoke last fall at the Institute of World Politics in Washington, DC, about Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s The Vietnam War. The following is based on his presentation there and was originally published in the Winter 2018 issue of Providence‘s print edition alongside other reviews of the PBS documentary, including Mark Moyar’s “What Ken Burns Omits From The Vietnam War.” Last fall we also published Mac Owens’ “Mission Failure: Burns & Novick’s The Vietnam War Misses its Target” and “A Failure to Discern: Burns & Novick’s The Vietnam War is Bad History.” Moreover, in the Winter 2018 issue, Eric Patterson explains how the Christian just war tradition applies to the war in “Just War & National Honor: The Case of Vietnam.” To read the following article in a PDF format, click here. To receive future issues as soon as they are published, subscribe for only $28 a year.

From my perspective the Ken Burns and Lynn Novick production of The Vietnam War had but one objective: to reinforce the standard anti-war narrative that the Vietnam War was unwinnable, illegal, immoral, and ineptly conducted by the allies from start to finish.

Their storyline is not very complicated: War is hell. Americans who opposed the war—good. Americans who fought in it—inept, even pitiable. North Vietnamese—admirable. South Vietnamese—hardly worth mentioning. War is hell. Let’s all make nice.

Burns and his associates have appeared at a large number of preview events. I attended one such session at the Newseum in Washington, and was impressed by their self-regard and self-satisfaction. They apparently now view themselves as the premier historians of the Vietnam War, and they are candid in stating their most basic conclusions. Burns told us, “You can find no overtly redeeming qualities of the Vietnam War.”

I hope I may be forgiven for stating my own conviction that he is in that profoundly wrong, as he was in referring disparagingly to what he called Americans’ “puffed-up sense of exceptionalism.” Clearly Burns does not much like America, an outlook that permeates his work.

In this production, Burns goes about making his case by—contrary to his and his associates’ claims that theirs was a historically respectable and unbiased account—skewed and unrepresentative content and commentators, lack of context, and crucial omissions.

Omissions

Those omissions are a damaging flaw in the Burns opus. The great heroes of the war, in the view of almost all who fought there (on our side), were the Dustoff pilots, and the nurses, and the forward air controllers. We don’t see much of them. Instead we see, repeatedly, poor Mogie Crocker, who we know right away is destined to get whacked. We see over and over again the clueless General Westmoreland, but learn nothing of his refusal to provide modern weaponry to the South Vietnamese or his disdain for pacification. We see precious little of his able successor, General Abrams. We see (and hear) almost nothing of William Colby—the CIA’s Chief of Station, Saigon—and his brilliant work on pacification. And so on. These are serious failings in a film that bills itself as “a landmark documentary event.”

Lack of Context

The series opens in Episode 1 with, in my strongest impression, a lot of noise. Helicopters roar around; explosions abound; small arms and artillery provide the prevailing atmosphere. This serves very well to underpin Burns’ contention that “war is hell,” and his statement at the Newseum preview that “we need to remind people of the cost of war.”

It does not, however, do a lot to establish Burns and company as the historians he maintains they are. Most historians, at least in my judgment, would have begun a series on the war by providing some context, and some background, on how and why the war began, and how and why the United States became a party to it, and what impelled a succession of US administrations to view it as in America’s interests to do so. But instead we got noise.

Research, Content, Commentators

What of the research? We are told the Burns team spent ten years on this project, and that in the course of it they interviewed more than 80 people. I know writers, working alone, who have interviewed several hundred people for a single book. The Burns team averaged eight interviews a year, an interview every month and a half, over the decade. Not impressive, at least to me; certainly not comprehensive.

At the Newseum preview, for instance, I met one General Merrill McPeak, United States Air Force, Retired, a former Air Force Chief of Staff. He was giddy with excitement over the role he had played in making the series, describing how he had made repeated trips from his home in Oregon to the Burns studio in New Hampshire to help with the production, and how he had seen the finished product “several times” and was immensely pleased with it.

We (the rank and file of preview attendees) had, of course, not seen any of the product yet. When we did, we saw that same imbecilic General McPeak proclaiming his view that in Vietnam the United States had been fighting on the wrong side. Apparently, in his mind, we should have been helping the Communists defeat the South Vietnamese.

Later, it is said, McPeak got so much negative feedback that he “withdrew” the comment, as though such a thing might in some mystical manner even be possible. But instead he is, forever, on record as having not only lent himself wholeheartedly to the creation of this terribly flawed version of the war, but having gone the last mile in endorsing its anti-war bias. Sorry, General, too late to back out now. Too late to rescue even a shred of integrity or reputation. You are a Burns man forever.

My email to him was brief: “You are, sir, a fool.” End of message. I’m sure his response will be along one day soon.

Dependence on Sponsors: Outcome Not Inevitable

Nowhere in this production is it explained that both sides in the war—North Vietnam and South Vietnam—were wholly dependent on outside sources for their means of making war. As we all know, the North obtained its weapons, fuel, and so on from Communist China and the Soviet Union. South Vietnam, of course, obtained like support from the United States. Until it did not.

Nowhere is it shown how valiantly and effectively the allies fought—and as US troop withdrawals continued it was more and more the South Vietnamese who were carrying the load. The South Vietnamese continued to fight for their freedom even after the United States had withdrawn all its forces, and even after the Congress of the United States had dishonorably slashed US financial and materiel assistance to them.

Evidence of how valiantly the allies fought could be found even in enemy sources. North Vietnamese General Tran Van Tra, for example, admitted that by the time of the January 1973 cease-fire:

Our cadres and men were exhausted. All our units were in disarray, and we were suffering from a lack of manpower and a shortage of food and ammunition. So it was hard to stand up under enemy attacks. Sometimes we had to withdraw to let the enemy retake control of the population.

But we didn’t learn of that from the Burns version of the war.

While you would never know it if you relied on Burns for your knowledge of the war, it did not have to end as it did. The Congress of the United States decided that it should and, depriving our ill-fated South Vietnamese allies of the means of continuing to fight (while the Communists received greatly increased support from their backers), made it be so.

Veterans

I was particularly interested in the veterans who got to speak, and what the whole program had to say about veterans. Burns is deeply interested in My Lai and any other instances of misbehavior by American troops, but he has next to nothing to say of the many, many heroic actions by medevac pilots, nurses, forward air controllers, the ordinary infantryman, or advisors.

Vietnam veterans—two-thirds of them volunteers, in dramatic contrast to the “greatest generation” of World War II, two-thirds of whom were draftees—said after the fact that overwhelmingly (91 percent) they were glad they had served. And an amazing two-thirds (67 percent) said they would serve again, even knowing the outcome of the war. Burns could not find time in his allotted 18 hours to mention that outlook.

General Westmoreland

Burns portrays Westmoreland, whose mindless war of attrition squandered four years of support by the American people, the Congress, and even much of the media, as a hero he never was.

The film describes Westmoreland as “a decorated hero from World War II.” In fact, Westmoreland was a battalion commander in North Africa and Sicily, but a division staff officer through the rest of the war. In three wars he never received a single decoration for valor or bravery.

The film goes on to (falsely) laud what Burns calls Westmoreland’s “impressive record,” adding that “the men he led in Normandy called him Superman.” Westmoreland led no men in Normandy. He was by then a division staff officer, in the 9th Infantry Division, which landed at Utah Beach on D+4.

Advisors on the Film

Burns’ chief advisor—there is only one listed—was Thomas Vallely, a member of Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Other advisors included the imbecilic General McPeak, with his view that the United States was fighting on the wrong side. There is also the pathetic Mai Elliott, who uttered—regarding the fall of Saigon and conquest of the South by the invading communists—the most inane comment in the entire 18 hours: “I didn’t care which side won. To me, Vietnam won. The Vietnamese people won because they could now live normally.”

Then came the bloodbath—but this isn’t mentioned at all.

Burns’ Intent

Someone wrote about the production that Burns somehow missed his chance to tell the true and accurate story of the war. I don’t think that is right. I think Burns did exactly what he set out to do: reinforce with all the might of his vaunted film-making skills the standard anti-war narrative.

In a New York Times op-ed piece entitled “Vietnam’s Unhealed Wounds” and with a shared byline, Burns and Novick lecture us on how what they call “the troubles that trouble us today” are the result of, they claim, “seeds…sown during the Vietnam War.” They catalog those troubles as “alienation, resentment and cynicism; mistrust of our government and one another; breakdown of civil discourse and civic institutions; conflicts over ethnicity and class; [and] lack of accountability in powerful institutions.” It is apparently their view that, had we not been involved in the Vietnam War, those troubles would not be afflicting us today.

Conclusion

Any competent historian, it seems to me, would have found room to emphasize at some crucial points along the way that it was armed aggression by the North Vietnamese that led to all this bloodshed and agony. Burns does not.

The North Vietnamese aggressors are treated with respect, even admiration. Nowhere is it admitted that the communist way of war deliberately featured bombs in schoolyards and pagodas, murder of schoolteachers and village officials, kidnapping and impressment of civilians, indiscriminate rocketing of cities.

The “boat people” and other émigrés now living in America and elsewhere in the free world have with great courage and industry made new lives for themselves and their families. They get little credit from Burns, who also does not deign to explain their determination not to live under the repressive communist regime that had seized control of their country.

When we get to the end of Burns’ long, sad story, we find South Vietnam in the iron grip of its supposed “liberators,” and, looming, is the bloodbath that he, Mai Elliott, and others cannot see or will not acknowledge. There will follow a half century (so far) of a Vietnam known as one of the most backward, repressive, and corrupt societies in the world.

Former Viet Cong Colonel Pham Xuan An later described his immense disillusionment with what the Communist victory had meant to Vietnam: “All that talk about ‘liberation’ twenty, thirty, forty years ago produced this: this impoverished, broken-down country led by a gang of cruel and paternalistic, half-educated theorists.” Burns says nothing of all that. It does not accord with his narrative of choice.

In all the materials Burns distributes advertising the broadcast, he repeats the mantra: “There is no single truth in war.” But there is such a thing as objective truth, elusive though it may be. What we have here is preferred “truth” as seen through the Burns prism.

In the Newseum discussion, Burns was surprisingly upfront in describing his objective in making The Vietnam War and his methods in realizing it. They had not been interested in dry facts, he told us, “but in an emotional reality.” And, claiming objectivity, Burns insisted that in making the film they had not, as he put it, had their “thumb on the scale.” But only moments later he stated his conviction that: “We need to remind people of the cost of war.” Perhaps someday there will be a sequel reminding people of the cost of losing a war.

Finally, the idea that this deeply flawed version of the war and those who fought it might somehow facilitate “reconciliation,” as claimed by Burns, can only be viewed as fatuous. There is no middle ground, and the Burns film demonstrates, if nothing else, just how deep and unbridgeable the divide remains.

The Washington Post, having a good day, in its Editorial of September 17, 1996, acknowledged this:

The American role in the Vietnam War, for all its stumbles, was no accident. It arose from the deepest sources—the deepest and most legitimate sources—of the American desire to affirm freedom in the world.

You would not gather that from the Burns film, and that is how it is most profoundly and fundamentally wrong.

_

Lewis Sorley (PhD, Johns Hopkins) is a third-generation graduate of West Point. His Army service included tank and armored cavalry units in Germany, Vietnam, and the US, Pentagon staff duty, and teaching at the United States Military Academy and the Army War College. He subsequently served as a senior civilian official of the Central Intelligence Agency. In 2009 he was the first Gottwald Visiting Professor of Leadership and Ethics at the Virginia Military Institute. He has been named a Distinguished Eagle Scout by the Boy Scouts of America, an Outstanding Alumnus by the Army War College, and a Distinguished Graduate by West Point.

His many books include three highly awarded biographies: Thunderbolt: General Creighton Abrams and the Army of His Times, Honorable Warrior: General Harold K. Johnson and the Ethics of Command, and Westmoreland: The General Who Lost Vietnam. His book A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.

Photo Credit: The Three Soldiers on the National Mall in DC. By Marc LiVecche.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024