In this article based on remarks given at the Institute of World Politics, Mark Moyar critiques Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s documentary The Vietnam War. This article was originally published in the Winter 2018 issue of Providence‘s print edition. To read the article in PDF format, click here. In the same issue, Eric Patterson explains how the Christian just war tradition applies to the war in “Just War & National Honor: The Case of Vietnam,” and previously on our website Mac Owens criticizes the documentary in “Mission Failure: Burns & Novick’s The Vietnam War Misses its Target” and “A Failure to Discern: Burns & Novick’s The Vietnam War is Bad History.” To receive future issues as soon as they are published, subscribe for only $28 a year.

In his own remarks, Mac Owens mentioned an essay by Jim Webb, the decorated Vietnam combat veteran, writer, and former US senator. That essay, “Heroes of the Vietnam Generation,” pairs well with an earlier essay, “Peace? Defeat? What Did the Vietnam War Protesters Want?,” which was also published by the American Enterprise Institute, in 1997. Both are very useful, especially for those who didn’t live through the Vietnam era, for understanding some of that generation’s dynamics.

Webb discusses how it was really the first time in US history when a lot of people argued not going into the military was actually a good thing, and this sentiment has guided how a lot of people look at the Vietnam War. In order to justify not serving in the military at that time, many described the war as unjust, unnecessary, and unwinnable. While I can’t read Ken Burns’ mind, if you look at his documentary The Vietnam War, it certainly seems to support this mentality.

We know Burns opposed the war at the time and decided not to go to Vietnam. While producing the documentary, he insisted he would only call balls and strikes to make a neutral, objective production. Anyone familiar with the war should quickly see how Burns overwhelmingly sides with the view that the war was unjust, unnecessary, and unwinnable, and how he omits information that contradicts this interpretation. While there are some factual inaccuracies, the biggest problems with the documentary are with what he doesn’t include.

When Vietnam was divided into two in 1954, the Vietnamese Communists and French agreed the country would unify and hold an election in 1956. When the documentary says the South Vietnamese government did not go along with plan, it repeats the old insinuation that Saigon opposed the Vietnamese people’s will. However, Burns omits that most South Vietnamese—as well as the Americans—were convinced that Ho Chi Minh and his Communists would intimidate the Northern Vietnamese, whom they controlled, into voting unanimously for him. Since the North had a bigger population, such coercion would practically make the country Communist. So, the South did not go along.

Not incidentally, by the way, the Saigon government was not even party to the 1954 agreement. But Burns and his co-producer Lynn Novick heap scorn on the young government that took control of the South in 1954. They, as is the traditional anti-war narrative, insist it was a bankrupt government.

Burns later highlights the Battle of Ap Bac in January 1963, in which the South Vietnamese forces did not perform very well, and then he tries to portray that fight as representative of the South’s abilities under President Ngo Dinh Diem. But, in fact, the South Vietnamese government was victorious in almost every other battle in the year before and after Ap Bac.

The Vietnam War doesn’t talk very much about the strategic rationale for the United States’ involvement in Vietnam, which was the so-called domino theory. There’s little mention of the legitimate concern that if South Vietnam fell then other countries in the region would also fall to Communism. The series mentions it at the beginning, but then the whole issue fades from the scene. However, domino theory does play out during this time. The most critical country in Southeast Asia from the American perspective was not Vietnam. It was Indonesia, a huge, strategically located country with massive natural resources. It also happened to have an anti-Communist coup at the end of 1965, which I think was clearly the result of American intervention in Vietnam. But the Burns production mentions nothing about that.

These types of selective omissions continue as the series progresses. Burns and Novick focus on six battles in the episodes covering 1966-67, and in each they go out of their way to highlight errors that the Americans committed as well as American casualties. They produce the impression that this was simply how the war was in 1966-67. Well, as it happens, when the series aired I was working on chapters covering those years in my book on the war. There were actually hundreds of battles then, and if you wanted to cherry-pick the worst six for the Americans, you would have chosen the same half-dozen selected by Burns. In fact, most of the battles in that period were overwhelming victories for the United States.

The series also leaves out the declining support among the Vietnamese for the Communists. In fact, I think the population never really cared about Marxist-Leninist ideology per se. But the Communists sold them a sort of snake oil and told everybody, for instance, that they would get to keep their land when they wouldn’t. Regardless, as the war turned against the Communists by 1967, Communist recruitment of South Vietnamese declined sharply, and that pace of recruitment continued to fall and never really recovered. Ultimately, about 200,000 supposedly die-hard Communists defected to South Vietnam.

The documentary’s narrator also tells us that 250,000 South Vietnamese troops were killed during the war. But we never hear why so many people were in fact willing to die for a government that was as bad as the documentary suggests. Burns and Novick give lots of information about Ho Chi Minh’s ideology, but we don’t really hear anything about the ideas that compelled these South Vietnamese to fight to the death on behalf of their country. In fact, there was a strong, growing sense of nationalism within South Vietnam.

From the very beginning, The Vietnam War has a sense of impending doom. The music is lugubrious, giving the sense that the outcome is foreordained and nothing could be done about it. This again reinforces the idea that the war was always unwinnable, a total lost cause. However, more and more evidence suggests that the war could have been won. American strategic choices, in some respects, account for our inability to take advantage of those opportunities.

One of those choices concerned America deploying ground forces. The US limited troops to South Vietnam, despite a lot of pressure from the military to go into Cambodia, Laos, and North Vietnam. We’ve now heard from the North Vietnamese that General Giáp, one of the People’s Army’s primary leaders, believed that if the Americans had expanded the boundaries of the war, the US could have thwarted him with about 250,000 troops, which is less than half of what we ultimately deployed in the South. We also now know the Chinese were not interested in getting involved. Concern that they would, as they did in Korea, was one of the main arguments for why the US didn’t enter the North. In fact, we know from the Chinese side that the they wanted nothing to do with the war or any other conflict with the United States.

The Kennedy administration’s support for a coup in November 1963 against the Diem government was another catastrophic choice made by the United States. A lot of evidence from the Communist side now suggests this coup sabotaged what in fact had been an effective war effort in the South.

Congress’ decision to slash aid and prohibit American military actions in South Vietnam after the Paris Peace Accords in 1973 was another ill-fated choice. The Easter Offensive of 1972 had shown that the South Vietnamese Army could fend off the North Vietnamese if they had American aid and air support. We took that away.

Burns and Novick make a very conscious effort to say they would not malign Vietnam veterans, as so much of the previous anti-war history had done. To some extent they avoid overt disrespect, but I think they still do a disservice to veterans. The Vietnam War interviews a huge number of anti-war veterans. Also, the Gold Star Mother interviewed happens to be one of the few who opposed the war. Likewise, the prisoner of war whom the documentary focused upon happens to be married to one of the only anti-war POW wives. Clearly, this is a selective effort trying to convince viewers that there was much more anti-war sentiment amongst the military and their families than actually existed. Burns presents very little about American soldiers’ camaraderie and pride. I think this is very much a deliberate attempt to undermine veterans’ experiences. The only times the documentary shows this sort of pride or enthusiasm is when it shows the North Vietnamese, who probably had less to be enthusiastic about since they lost so many times. We don’t hear anything about the 259 Americans who received the Medal of Honor, or the tens of thousands who earned other awards, or the countless others who displayed extraordinary valor but did not receive an award for it. Instead, the series leads viewers to believe that Vietnam veterans were victims of the war, that there was not much redeeming about them, and hence, again, that maybe going to Vietnam wasn’t the right thing to do.

The reason I started studying the Vietnam War 25 years ago was due to my belief that the anti-war left unfairly besmirched America’s Vietnam veterans. Although Burns and Novick don’t besmirch veterans as flagrantly, their misrepresentation of the war and its warriors has reopened old wounds. It’s not just Vietnam veterans’ reputations at stake; how we view this war shapes how we view ourselves as Americans. Burns and his interviewees go out of their way to claim that the Vietnam War debunked the notion of American exceptionalism. They seem to want us to believe that the US, the world’s first modern democracy and principal guardian of the world order since 1945, is on a moral par with North Vietnam, a dictatorship that waged several brutal wars in the name of Marxism-Leninism and slaughtered tens of thousands of civilians before deciding that Marxism-Leninism wasn’t such a good idea.

This aversion to American exceptionalism and patriotism has pervaded too much of our society since the Vietnam War. For those of us who think the US is a force for good in the world, that our country is so good that we’d risk our lives for it, the accurate retelling of the Vietnam War is imperative. That’s why I think it’s important to let the country know just how fallacious the Burns series is.

_

Mark Moyar (PhD, Cambridge) is the Director of the Project on Military and Diplomatic History at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, DC. The author of six books and dozens of articles, he has worked in and out of government on national security affairs, international development, foreign aid, and capacity building. His newest book is Oppose Any Foe: The Rise of America’s Special Operations Forces (2017). His other books include Aid for Elites: Building Partners and Ending Poverty with Human Capital (2016), Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965 (2006), and Phoenix and the Birds of Prey: Counterinsurgency and Counterterrorism in Vietnam (1997, revised 2007).

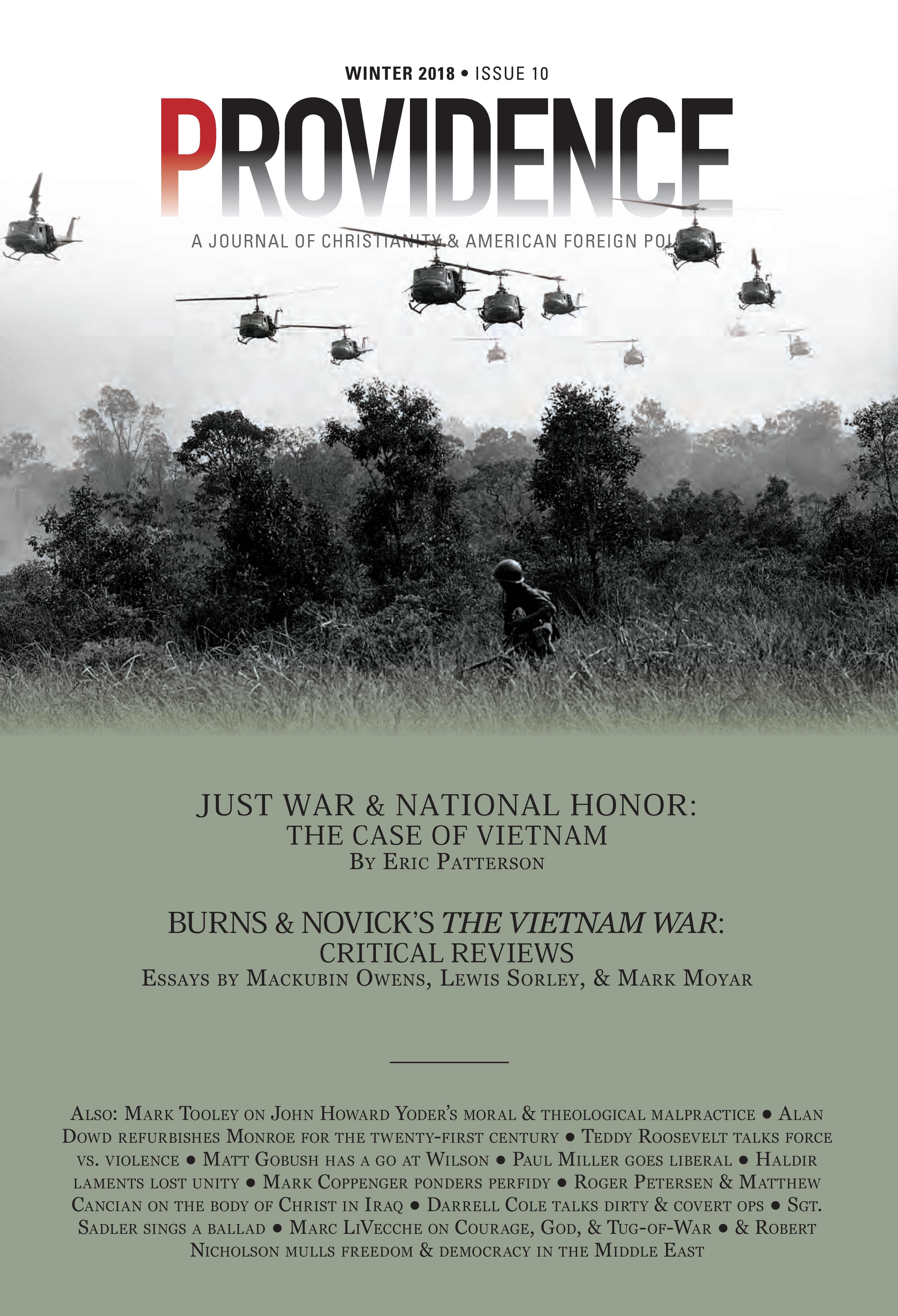

Photo Credit: A Huey Gunship swoops over the heads of Marines of M Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines, as they start their sweep near Que Son, 30 miles southwest of Da Nang. May 30, 1970. Sgt. R.R. Nauber. Source: National Archives.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024