Recently, tensions between Armenia, a predominately Christian country, and Azerbaijan have flared up again. This conflict usually focuses on the Nagorno-Karabakh (or Artsakh) region in Azerbaijan, whose population is mostly Armenian by ethnicity. A war was fought over the disputed region from 1988 to 1994, leading to a decisive Armenian victory. In 1994, Russian negotiations led to a ceasefire, but the parties never signed a peace treaty.

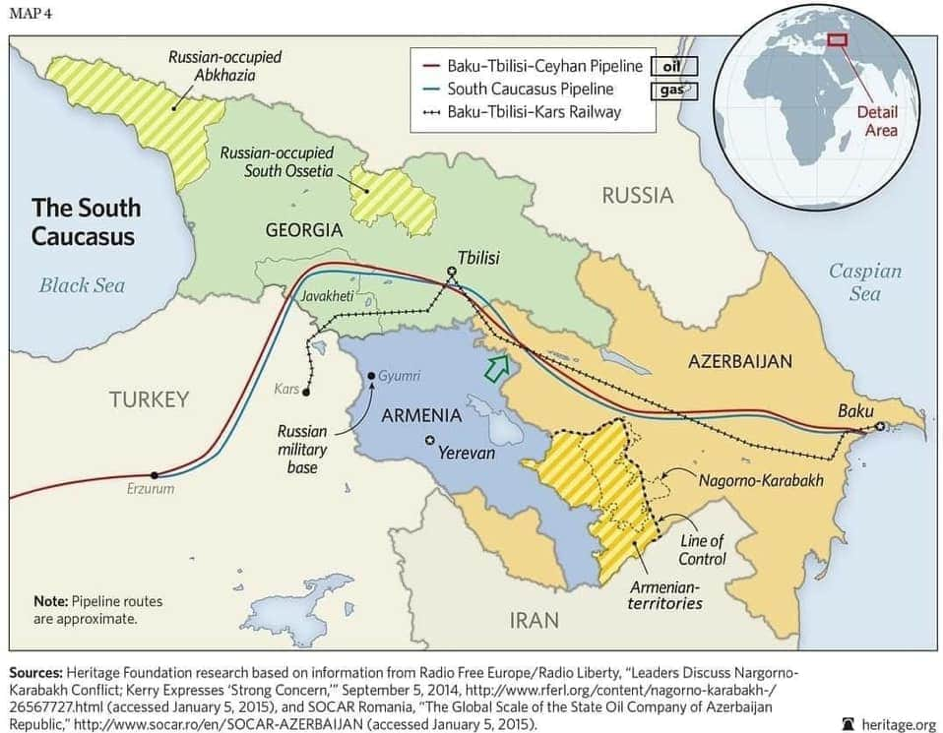

Since then, there have been several skirmishes between the Armenians and Azerbaijanis, including in 2008, 2010, 2014, and 2016. These primarily took place around the Line of Contact at Nagorno-Karabakh. However, the clashes that began on July 12, 2020 took place further north in the Tavush (or Tovuz) region (see map).

The green arrow indicates the location of skirmishes in July 2020.

Numerous factors play a role in this conflict, but this article focuses on Russia’s contribution. As said previously, the Russians helped broker a ceasefire in 1994, but their involvement started much earlier during tsarist times. For now, it suffices to say that the territories of modern-day Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Nagorno-Karabakh were completely under Russian imperial rule by 1828.

About 100 years later on July 5, 1921, the Soviets established their rule, and Joseph Stalin included the Nagorno-Karabakh region in the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR). He made this decision one day after the Caucasian Bureau of the Russian Communist Party Central Committee decided that the territory should have been part of the Armenian SSR instead. This move was a cynical part of the Soviets’ divide-and-conquer strategy in the Caucasus.

About 75 years later, the Soviet Union disintegrated, and the Armenians and Azerbaijanis concluded a ceasefire. However, Russia’s long historical influence in the region did not stop after 1994.

Today both Armenia and Azerbaijan are militarily dependent on Russia. In 1994, both countries joined the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a military alliance comparable to NATO in purposes but with a leading role for Russia. After a few years, Azerbaijan withdrew from the organization while Armenia remained. But Azerbaijan’s withdrawal did not completely sever its military relations with Russia. Instead, according to the Arms Transfers Database of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), over half of Azerbaijan’s military equipment bought between 2014 and 2019 originated from Russia. So the countries depend on Russia, which is thus the key potential arbitrator to the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict.

Why then is the conflict still considered “frozen”? If Russia could have solved the conflict, why didn’t it? Simply put, the conflict’s continuation is in Russia’s interests. Resolving the conflict would relinquish a means of exerting pressure on both countries, which Russia needs for a couple of reasons.

First, Russia has interests in the Caspian Sea, which contains numerous natural resources, including hydrocarbons. The Soviet Union and Iran agreed on how to share these resources, but after the dissolution of the USSR, some newly independent states held that the exploitation of the seabed was not adequately addressed. Today the status of the seabed with all its natural resources remains unclear. Although countries have demarcated borders and oil and gas extraction is possible, whether countries should build pipelines across the Caspian Sea is still a contentious issue.

Kazakhstan exports a lot of oil and gas to Russia, but it would like to export more directly to Europe through the Caucasus. This would diminish Russia’s leading energy position in Europe. It is therefore in Russia’s interest to prevent the building of pipelines in the Caspian Sea, and during negotiations Russia unreservedly leverages Azerbaijan’s dependence to thwart their construction.

Second, the matter of pipelines is a broader theme in Russo-Azerbaijani relations. Since mid-2006, the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline has transported oil from Azerbaijan, through Georgia, and to Turkey, from where it can be distributed to Europe. This has been a thorn in the side of Russia because it reduces the country’s power to control energy supplies in Europe.

Third, Turkey is eyeing an opportunity to increase its influence in the Caucasus. Over the last few years, Turkey has undertaken actions to become a more independent geopolitical player with less Western influence. So Turkey let Russia build a pipeline to Istanbul , purchased an S-400 missile system, and (seemingly) cooperated with Russia in Syria. The West has criticized Turkey for these actions. However, the United States and others should not mistake Turkey’s actions as a prelude to an alliance change. Turkey supports and supplies the UN-recognized government in Libya, whereas Russia supports the rival government. Turkey is also the most avid proponent of Georgia entering NATO (a nightmare scenario for Russia). Rather than aligning itself with Russia, Turkey desires to play a more influential role in the Caucasus, which its rhetoric during the recent skirmishes shows.

As said before, the latest clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan took place in the Tavush region, which is quite close to where the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline enters Georgia. Moreover, on July 17, a few days after the skirmishes between the countries began, Azerbaijan announced that it would restart its oil exports to Russia, which were halted in January. Since that announcement, reported violations of the ceasefire have starkly decreased, showing that Russia’s role (not Turkey’s, as some have suggested) is decisive.

In the future, Armenia could choose to diversify its foreign relations by expanding its relations with Iran to include a military aspect. In such a case, Russia could easily influence Azerbaijan to try its luck against Armenia, thereby forcing Armenia back into Russia’s sphere. This way, Russia would retain its significant role in the Caucasus. So any solution to the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict without Russia’s blessing is illusory.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024