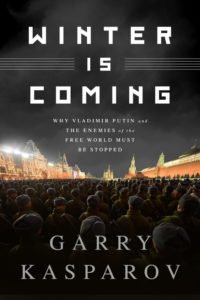

Providence’s Spring 2016 issue of the print edition ran a comparison of two books about Russia, Garry Kasparov’s Winter is Coming: Why Vladimir Putin & the Enemies of the Free World Must Be Stopped and Bobo Lo’s Russia & the New World Disorder. The following review of Kasparov’s Winter is Coming expands upon the print edition’s version. To read the shorter original book comparison in a PDF format, click here. To subscribe to future print edition issues, click here.

Suggesting that the old Soviet Union is as dangerous as the modern Russian Federation would be foolish, not least because modern-day Russia is neither driven by a global ideological agenda nor has the economic strength to afford such an agenda. However, as Garry Kasparov argues in Winter is Coming, Vladimir Putin and his kleptocratic government still poses serious risks for the world’s democracies (and not just those in the West) as the oligarchs maintain their wealth and power by any means necessary. Those democracies, according to Kasparov, deserve much of the blame.

A Russian activist and former chess champion, Kasparov explains in great detail the dynamics that created Russia’s mafia-style government, starting at the end of the Cold War. Arguing against the “humiliation myth” that asserts the West purposely disgraced Russia after the Soviet Union collapsed, Winter is Coming relates how Western democracies actually bankrolled the crumbling USSR with billions of dollars to prevent its collapse (6-9, 27-30). He summarizes, “Ironically, the roots of Russia’s descent back into totalitarianism can be traced to the West doing too much to respect the legacy of the USSR as a great power, not too little” (29). Foolishly and futilely hoping that appeasement would lead to a more cooperative relationship, multiple American presidents from both parties ignored atrocities and human rights violations when, according to Kasparov, they should have spoken hard truths to the Russian people about the real nature of their government (50-58, 80-81, 156-158, 209-211). Once the oligarchs dismantled democratic checks, they perfected kleptocracy. Putin emerged as a mafia-style “capo di tutti capi” who eliminated noncompliant oligarchs and now enables the remaining oligarchs to efficiently rob Russians’ wealth. Public theft became the state’s raison d’être. Democracies, complicit in these crimes, still enable Putin to purchase the support he needs because they accept the ill-gotten wealth—such as by letting banks in London, New York, and elsewhere take stolen cash, or by selling yachts to cronies. As long as oligarchs can use safe Western banks and enjoy Western luxuries, there is no need to overthrow their lucrative arrangement (158-165, 205-208). Meanwhile, everyday Russians cannot challenge Putin peacefully or even organize against him.

A Russian activist and former chess champion, Kasparov explains in great detail the dynamics that created Russia’s mafia-style government, starting at the end of the Cold War. Arguing against the “humiliation myth” that asserts the West purposely disgraced Russia after the Soviet Union collapsed, Winter is Coming relates how Western democracies actually bankrolled the crumbling USSR with billions of dollars to prevent its collapse (6-9, 27-30). He summarizes, “Ironically, the roots of Russia’s descent back into totalitarianism can be traced to the West doing too much to respect the legacy of the USSR as a great power, not too little” (29). Foolishly and futilely hoping that appeasement would lead to a more cooperative relationship, multiple American presidents from both parties ignored atrocities and human rights violations when, according to Kasparov, they should have spoken hard truths to the Russian people about the real nature of their government (50-58, 80-81, 156-158, 209-211). Once the oligarchs dismantled democratic checks, they perfected kleptocracy. Putin emerged as a mafia-style “capo di tutti capi” who eliminated noncompliant oligarchs and now enables the remaining oligarchs to efficiently rob Russians’ wealth. Public theft became the state’s raison d’être. Democracies, complicit in these crimes, still enable Putin to purchase the support he needs because they accept the ill-gotten wealth—such as by letting banks in London, New York, and elsewhere take stolen cash, or by selling yachts to cronies. As long as oligarchs can use safe Western banks and enjoy Western luxuries, there is no need to overthrow their lucrative arrangement (158-165, 205-208). Meanwhile, everyday Russians cannot challenge Putin peacefully or even organize against him.

In addition to describing how the Russian political system enriches Putin and the oligarchs, Kasparov uses his well-honed op-ed writing style to respond to Kremlin defenders’ accusations and excuses. Specifically, he uses his own experience as a Russian opposition figure to demonstrate how the kleptocracy maintains its power.

Some of the Kremlin defense could be seen when the Russian think-tank Primakov Institute of World Economy & International Relations’ director and deputy director spoke at the Atlantic Council last December. They were presented as being close to the Kremlin and having Putin’s ear, and the director, Alexander Dynkin, serves on the Presidential Council. They provided a Russian perspective rarely seen in the US, albeit a deeply biased perspective that must be viewed in the way a jury should consider a lawyer’s description of his client. For instance, Dynkin argued that Putin and his United Russia party are dominant not because the state has suppressed freedoms but because the opposition parties are weak and disorganized. Moreover, Feodor Voitolovsky, the Institute’s deputy director, complained that the West wrongly accuses Russia of suppressing freedom of the press. For proof he cited how a Russian mayor had recently been ousted after online protests, saying the politician would have never lost his job if Russia lacked political freedoms.

Though their presentation was instructive, taking them at face value was difficult, especially when the previous month I had met Vladimir Kara-Murza, the deputy leader of the Russian opposition People’s Freedom Party (PRP-PARNAS) who had been poisoned in May 2015 while in Moscow. Though Dynkin asserted that Russia lacks a viable opposition party because the opposition is weak, he omitted that opposition parties are weak precisely because their leaders often wind up dead.

A vigorous rebuttal to claims like those of Dynkin and Voitolovsky, Winter is Coming clearly demonstrates how Putin’s government targets critics. Kasparov offers the best repudiation to Kremlin misdirection when he details his experience leading an opposition party. Before the 2008 Russian presidential elections, he tried to complete the difficult nomination process to be placed on the ballot. First, they had to receive two million signatures within five weeks, which became difficult because only forty thousand could come from a single district like Moscow. Then, each candidate had to hold a nominating convention with five hundred supporters under one roof, which became impossible when no one would allow his party a space for the convention. One venue eventually did, but then suddenly cancelled just before the event for technical difficulties, even though the next night a Kremlin-backed candidate used the same room. Because he could not hold a convention before the deadline, his name did not appear on the ballot (176-178). He explains, “In Russia the opposition isn’t trying to win elections; we’re trying to have elections” (176, emphasis in the original).

Therefore, Kasparov rejects the widely-held belief that Putin is popular at home. To this point he retorts:

If Putin is so popular, why not have free and fair elections and a free media? Persecuting bloggers and arresting a single protestor standing in the town square holding an anti-Putin sign does not strike me as the behavior of a popular ruler.

The entire definition of approval and popularity of a democratic leader has no application in an autocracy. When there is only one restaurant in town and it has only one item on the menu, and no other restaurants are allowed to open, is it popular? … This leads into another of the myths, that the opposition was simply not competent or charismatic enough to challenge Putin … Our members were banned from the media, slandered, prohibited from holding meetings and rallies, frequently physically assaulted, raided and harassed by the police, and blocked from appearing on ballots. What brilliant and coherent message, what transcendent leader, would have led us to power under those circumstances? (180-181)

If Putin’s mafia-style government could maintain its wealth and power merely through suppressing political freedoms, democracies could safely ignore this problem (unless they shared a border with Russia). However, as Kasparov argues, Russia “exports corruption” that weakens democracies. Putin seeks to “co-opt and quiet the West by recruiting prominent individuals. When everyone is guilty, no one is guilty, goes the logic” (164). For instance, the oligarchs offer lucrative deals to Western investors and companies who then take the wealth back home and oppose the sanctions that could force Russia to reform (158-159). Though democracies may encourage Russia to protect human rights, Kasparov argues:

The Kremlin was not changing its standards; it was imposing them on the outside world. The mafia corrupts everything it touches… Putin and his cronies received the stamp of legitimacy from Western leaders and businesses while making those same leaders and businesses complicit in their crimes. (161-162)

Instead of encouraging political reforms, economic engagement allowed Russia to buy “respect where it cannot be earned” (205). As corruption flows out of the Kremlin and spills onto democracies, it contaminates the democratic process itself. Kasparov warns against politicians and other leaders who downplay Putin’s threat:

Anyone who says they are still uncertain about Putin’s true nature at this point must be joking, a fool, or tricking us… [T]ricksters must be watched carefully. For at least a decade now, those who defend Putin either have something to gain from it or they are dangerously ignorant. (102)

These warnings seem reasonable, but whereas Winter is Coming effectively rebuts the Kremlin defenders, it does not provide sufficient evidence that democracies should be concerned about Russia exporting corruption. Ample evidence may exist, but the book should have been given a more thorough exposition.

Though he could do more to explain how Russia exports corruption, Kasparov does give several policy recommendations. For instance, democracies can use their economic power to pressure the oligarchs, though he advises against a complete boycott of Russia (164-165). Meanwhile, democratic leaders should speak directly to the Russian people about the kleptocracy, instead of appeasing Putin. He pointed to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and Voice of America as examples that helped his cause against communism (72-73). The book also insists that democracies should not ignore human rights, use them as bargaining chips for strategic purposes, or forget them when convenient (113).

Nevertheless, Winter is Coming mostly “preaches to the choir”, telling idealists what they like to hear without providing enough evidence to convert realists. Kasparov also seems to downplay how the US and other democracies may be forced to cooperate with Russia while pursuing essential strategic objectives. This cooperation may require pragmatic compromises that anger human rights activists. More importantly, the US must cooperate with China despite its human rights record. If the US treats the two countries inconsistently, a moral foreign policy could quickly turn incoherent. (For now China and Russia have lately behaved differently so deserve to be treated differently: e.g., Russian attack aircraft flew a mock bombing run on a US Navy destroyer in the Baltic Sea, while Chinese aircraft have been less provocative.) Threatening Russian oligarchs with sanctions may be easy when America has limited economic ties to Russia, but threatening Chinese autocrats could threaten America’s economy. Ultimately, some actions designed to promote political freedoms may be counter-productive if they limit the American prosperity that allows the US to use economic, military, and soft power to achieve its foreign policy.

Overall, Kasparov’s witty writing style plus his personal, on-the-ground perspective as a Russian activist make Winter is Coming a lucid and fascinating read. It is an essential book for those who view foreign policy through a human rights framework.

—

Mark Melton is the Deputy Editor for Providence. He earned his Master’s degree in International Relations from the University of St. Andrews and focuses on civil conflict and European politics.

Photo Credit: Red Square in the Snow. By ManWithAToyCamera, via Flickr.