This essay about just retribution and how it applies to Christianity first appeared in Providence‘s Spring 2016 issue of the print edition that was released last May. To read the original in a PDF format, click here. To subscribe and receive future issues of the print edition, click here.

Introduction

Three generations ago Dorothy Sayers chided the Christian church for its indifference toward theological foundations. The result of this deficiency, she lamented, was a church devoid of substance. Ethically, as she saw it, this dearth ended up paring “the claws of the Lion of Judah.”[i]

It is difficult to understate Sayers’ burden, for if the church’s condition in her day was unhealthy, in our own it may well be anemic. But this essay concerns itself neither with ecclesiology nor formal theology per se. Its burden, rather, is to identify a key deficiency in the way that much of the Christian community thinks about ethics and ethical issues. It is concerned to address the perceived opposition between—when not the outright divorce of—justice and charity. This perceived tension can be measured both in the literature written by professional (religious) ethicists as well as at the popular level.

This opposition, of course, is by no means confined to religious thought. The notion of retribution or punishment[ii], which is foundational to any construal of justice, has long been the scourge of social science. For several generations, social scientists (including not a few criminologists) have viewed punishment in general as detrimental to human beings. Alas, it was only a matter of time before religious ethicists and theologians began imbibing this prejudice and promoting it—in both academic and popular discourse.

Part of the task, then, of serious Christian thinkers, for whom culture and the common social good are to be taken seriously, is to develop the distinction between retribution—which is an intrinsically moral entity and which is lodged at the heart of justice—and revenge or retaliation. We shall develop this important distinction later in the essay, but suffice it to say that a failure to understand the fundamental difference between the two is a failure to exercise moral discernment. And in the end it manifests itself in a failure at the policy level, where the consequences of bad ideas are magnified exponentially.

Logically, three possibilities present themselves for our consideration:

- Retribution (i.e., punishment) and Christian love are one and the same and indistinguishable.

- Retribution and Christian love are polar opposites and unrelated.

- Retribution and Christian love co-exist and are able to merge in an ethically qualified way.

I reject option #1, and few people (in their right minds) would affirm it. There seems to be a case for #2, based on several factors. One might be a bad social environment in which one grows up—for example, father-absence or having an abusive parent. Another might be the aforementioned philosophical opposition, whereby it is assumed that punishment is harmful. Yet another factor might be theological opposition, several forms of which are identified further on.

Notwithstanding the force of arguments made on behalf of option #2, I shall reject these and argue for #3. When justice and charity are wed, unified, and working in symbiosis (rather than separated or viewed as conflicting), humans perform their moral duty, dignify the image of God in one another, and promote responsible social policy. Thus, we may speak of punishment or moral retribution, properly construed, as that which is just and not at odds with charity, properly construed.

I begin with an argument for the unity and symbiosis of justice and charity on the basis of theological and moral-philosophical assumptions rooted in the historic Christian tradition and natural law. Against this proposal, I examine influential voices that have contributed in substantial ways to posing opposition between justice and charity. Following this I identify representative voices within the wider Christian tradition that agree with my thesis. I conclude with reflections on the significance of the harmony of justice and charity as it concerns preserving the common good and undergirding responsible policy.

Justice & Charity in Concord: The Case for Just (i.e., Moral) Retribution

At its third annual ethics symposium, convened in 2012 at the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, the U.S. Army brought together both military and civilian ethicists, historians, political philosophers, and chaplains to reflect corporately on the ethics of coercive force in the contemporary geopolitical setting. One of the speakers addressed assembled attendees (Majors and Lt. Colonels) on the moral-philosophical underpinnings of what consensually has been understood as the mainstream of the just-war tradition, a rich tradition of (frequently Christian) moral reflection stretching from Ambrose and Augustine to Aquinas to Vitoria, Suárez, and Grotius to modern-day theorists such as Paul Ramsey, James Turner Johnson, and Jean Bethke Elshtain. The title of his address was instructive: “Justice, Neighbor-Love, and the Permanent in Just-War Thinking.”

The essence of his remarks was that the symbiosis of justice and charity undergirds and informs the tradition and doctrine of “just war,” properly understood. To divorce these two virtues, therefore, would be to do irreparable damage to the character of both justice and charity as well as to alter the very moral foundation upon which just-war thinking rests. Both justice and charity, he reminded his audience, are non-fluid in character; as quintessential human virtues, they are deemed universally binding, and hence, are “owed” to all people. As evidence of this universality, he noted, a trans-cultural “Golden Rule” ethic surfaces in the teaching of both Plato and Jesus. And in the Christian moral tradition, this ethic, wherein justice and charity embrace, gives embodiment to the natural law and finds powerful expression in the parable of the “Good Samaritan.”

Theological Considerations

It has been a confession of Christian theology through the ages that the nature and character of the trinitarian God are marked inter alia by incommunicable attributes such as eternality, infinity, omnipotence, omniscience, transcendence, immutability, invisibility, sovereignty, and self-sufficiency. A related attribute, which tends not to receive much attention, is that of indivisibility. This doctrine counters the notion—whether implicit or explicit—that the divine nature is constituted by separate parts. A God whose being is understood or assumed to be composite, thus, is assumed ultimately to be more creaturely than otherly and transcendent in nature.[iii] Divine attributes are not to be understood as additions, elements, trappings, or supplements—i.e., qualities that are “added” or in need of being “balanced.” They do not exist in a certain “combination.” At bottom, the Christian God is not a deity of parts or divisions,[iv] nor does he “develop” or “emanate.” Rather, his actions are an expression of his perfection, unity, and timelessness. We might even argue that God does not have attributes; he is his attributes. And for our purposes here, I am assuming that his love is his justice, that his judgments are his mercy, and vice versa, even when they manifest themselves in differing (and seemingly irreconcilable) ways.[v]

The ethical implications of the doctrine of divine indivisibility become readily apparent. Because the divine nature is not composite or a sum of many parts but rather a unity, divine action is to be understood not as a setting aside or “negating” of various attributes but rather as a different expression or form of the same attributes. To be sure, from the human standpoint, the qualities of divine mercy and compassion would appear opposites of divine judgment and wrath. And yet, historic Christian confession calls us to reject this “opposition” and affirm that these are but different manifestations of the same attributes. The divine nature, after all, does not change.

The ethical upshot of this doctrinal position requires reiterating. Divine justice and love may not be severed or viewed as standing in tension (or opposition). And because Christians are “called” to imitate the divine nature, they are prohibited from divorcing justice and charity as these “cardinal virtues” impact persons and people-groups. It is in this way—namely, creation and divine image-bearing—that the human moral impulse is to be understood. Christian theology posits that humans are created in the image of God; hence, we are to bear his likeness by mirroring the imago Dei through our lives and our actions.

A fundamental part of this image-bearing is to manifest and work for justice in the context of human relations. Motivation for this work is summarized by the so-called “Golden Rule” ethic that surfaces in the teaching of both Plato and Jesus: we do to others as we would want others to do to us. This entails advancing standards of moral good and resisting or countering evil. For Thomas Aquinas, precisely this—doing good and avoiding evil—constitutes the heart of the natural moral law, the “first principles of practical reason.”[vi] In his brief but richly discerning essay “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment,” C.S. Lewis argues that it is precisely because of the image of God in others, not in spite of it, that we hold fellow human beings accountable for their actions. To hold them accountable, Lewis insists, is to dignify the imago Dei in them, and to fail to hold them accountable is to disavow the imago Dei.[vii]

Lest one assume that Christian theology loosens the demands of justice by means of a presumed priority of love (an objection to be treated in the following section), two important qualifications are in order. First, the definition of “love” needs severe qualification. “Love” needs stripping of the cultural baggage to which we have grown accustomed. When we speak, in biblical and theological terms, of “loving one’s neighbor,” we understand charity to mean the desire for another’s best or highest. It is in this light that we are to understand “enemy-love” as taught by Jesus. We wish for fellow human beings what is best for them—even for criminals and evildoers. To restrain or inhibit evildoers is indeed best for them, best for society at large, and best for future offenders.

Secondly, the teaching of the New Testament is univocal in its emphasis: love fulfills the law, which is another way of saying that charity and justice are one and cannot be divorced. This is the explicit teaching of Jesus, Paul, and James.[viii] Consider the context of each of these. Jesus’ teaching is designed to counter contemporary religious thinking that might loosen the demands of the moral law. James is responding to tensions within an emergent Christian community in which the role of law is being hotly debated. And in the apostolic teaching recorded in Romans 13, Paul is arguing that justice as meted out by the governing authorities is divinely sanctioned for the express purpose of preserving justice and social order in a fallen world. In the apostle’s rationale, retributive justice and individual conscience are necessarily linked because of the “debt” of charity, which “fulfills the [moral] law.”

Moral-Philosophical Considerations

In the context of moral accountability and retributive justice, a further qualifying element requires comment—an element that not infrequently is ignored, if not denied. A common objection to punishment, both in the sphere of criminal justice and in the realm of foreign policy and international affairs, is that retributive justice is merely a pretext for vengeance and retaliation. And, clearly, revenge is not rooted in love of one’s neighbor.

The Christian moral tradition distinguishes the retributive act from revenge in important and unmistakable ways, based on intention. At its base, the moral outrage that expresses itself through retributive justice is first and foremost rooted in moral principle and not hatred or passion. Conceptually, revenge and retribution are worlds apart. Whereas revenge (i.e., vengeance or retaliation) strikes out at real or perceived injury, retribution speaks to an objective wrong. Because of its retaliatory mode, revenge will target both the offending party and those perceived to be akin; retribution, by contrast, is targeted yet impersonal and impartial, not subject to personal bias.[ix] It is for this reason that “Lady Justice” is depicted as blindfolded.

Moreover, whereas revenge is wild, insatiable, and not subject to limitations, retribution acknowledges both upper and lower limits[x] as well as the moral repugnance of both draconian punishment for petty crimes and of light punishment for heinous crimes. Vengeance, by its very nature, has a thirst for injury, delighting in bringing further evil upon the offending party. The avenger will not only kill but rape, torture, plunder, and burn what is left, deriving satisfaction from the victim’s direct or indirect suffering. Augustine describes this propensity as a “lust for revenge,”[xi] a motivation which causes C.S. Lewis to reflect, in the context of war:

We may [in wartime] kill if necessary, but we must never hate and enjoy hating. We may punish if necessary, but we must not enjoy it. In other words, something inside us, the feeling of resentment, the feeling that wants to get one’s own back, must be simply killed… It is hard work, but the attempt is not impossible.[xii]

The impulse toward retribution, it needs emphasizing, is not some lower or primitive instinct; rather, in Christian theological terms, it corresponds to the divine image present in all people. To treat men and nations, however severely, in accordance with the belief that they should have known better is to treat them as responsible moral agents. Civilized human beings will not tolerate murder and mayhem at any level, whether domestic or international; the uncivilized, however, will. “Civil society” will exercise moral restraint in responding to moral evil—a commitment that is rooted in neighbor-love and an awareness of the human dignity. The particular character of this response is twofold in its application: it is both (a) discriminating and (b) proportionate in its application of coercive force.[xiii]

In the sphere of human ethical endeavor, then, there exists—based on the character of God and the image of God in human creation—a unity (and therefore, symbiosis) between charity and justice. This unity must inform ethical theory and activity, including our understanding of retribution or punishment. Ethically, the separation of divine attributes is ruinous, mirroring weak theological foundations and in the end breeding disaster in terms of social and public policy. For this reason it is necessary to identify influential voices, particularly in religious ethics, which have contributed to the opposition or separation of justice and charity.

Justice & Charity in Conflict: Challenges to Symbiosis

The Priority of Love: Representative Voices

What unites many religious thinkers is the baseline conviction that Christian love is both the goal of human existence and the means to that goal. Hence, to treat fellow human beings merely as moral law or justice requires is not the same—nor as noble—as to love others as Jesus ostensibly requires of us.

In his important and defining Works of Love, Søren Kierkegaard argues for love’s transcendence by observing the anatomy—the very composition—of agape; it:

- is our supreme duty

- is a fulfillment of the law

- is our ongoing debt to others

- seeks not its own

- hides a multitude of sins

- believes and hopes all things; and

- abides forever

Kierkegaard poses the question, “What is it that is never changed even though everything [else] is changed?” His response: “It is love, …that which never becomes something else.”[xiv] Love is eternal, “the only thing that will not be abolished.”[xv] “You shall love” is “the royal law.”[xvi]

In the conclusion of Works, Kierkegaard writes tellingly: “The matter is very simple. Christianity has abandoned the Jewish like-for-like [i.e., an eye for an eye]… but it has established the Christian, the eternal like-for-like in its place.”[xvii] For Kierkegaard, the concept of restitution no longer exists with the advent of Christianity. In his “leap of faith,” love becomes the source and sum of ethics, a transcendent norm that lies beyond the natural law and any moral parameters.[xviii]

Perhaps the most sophisticated apology for love’s ethical primacy is found in the seminal work of Anders Nygren (d. 1978), for whom the Christian idea of love involves “a revolution in ethical outlook without parallel in the history of ethics.”[xix] As the title of his work indicates, the main competitor to agape is the Platonic concept of eros. The challenge is therefore twofold: to distinguish the two and to purify agape of socio-cultural notions that accrue over time.[xx] Nygren insists that agape is not merely a fundamental motif of Christianity; it is the fundamental motif.[xxi]

For Nygren, the character of love is understood as “unmotivated,” “indifferent to value,” and “blind” to the demands of justice.[xxii] This “blindness,” it is thought, results in forgiveness, which is gratuitous and foregoing of any corrective rights. God’s love, after all, is pure grace and doesn’t recognize merit or value. Therefore, the moral vision of the New Testament is not merely a “fulfillment” of the Old; it is a repudiation of law and justice as revealed in the Old.

One further exemplar, closer to our day, is sufficient for illustration. In the introduction to his book Moral Wisdom, James F. Keenan writes, “I believe we need to start with the primacy of love and specifically the love of God… If we start with love instead of freedom or truth, what happens? Why start discussions of morality…with love?” Three reasons, Keenan believes, justify this primacy: scripture, theology, and human experience.[xxiii]

Keenan’s position, that love is the starting point for morality—and not truth, for example[xxiv]—should give us pause. Yet, this assertion places him squarely in the mainstream of contemporary thinking about ethics. Generally assumed is that love and justice stand in tension or opposition, resulting in a “primacy” of love.[xxv]

The Priority of Love & Peace: Religious Pacifism

Given its basic pre-commitment to peace as “non-violence” (or peace as the absence of conflict), religious pacifism places love and justice in frequent conflict or opposition by diminishing the demands of justice in its reading of Scripture and extolling peace as the virtue of the “Kingdom of God.” In our day it finds its most forceful expression in the writings of people like John Howard Yoder, Stanley Hauerwas, and other Anabaptist types. At the risk of over-simplification, we may say that because of an ideological pre-commitment to “peace” and “non-violence,” certain tendencies affecting faith and ethics flow from this outlook—among these:

- the extolling of love and “peace” as the highest virtues

- the “Sermon on the Mount” as not only personal discipleship but statecraft

- the “turning of the other cheek” as the equivalent of “enemy-love”

- the assumption of a moral purity in the early (pre-Constantinian) church

- the assumption of a Constantinian decline and apostasy of the church (“Constantinianism”)

- the belief that the church, since the fourth century, with the exception of the “radical reformation” of the 16th century (the birth of Anabaptism), has been in apostasy

- the failure to distinguish between a just peace (pax iusta) and an unjust peace (pax iniqua)

- the failure to distinguish between force and violence

- the failure to distinguish contextually between Romans 12 and Romans 13

- the rejection of abiding moral law and the natural law

- a false dichotomizing of Old Testament and New Testament ethics

Lest the reader conclude that I am unfairly caricaturing religious pacifism, permit me to say that I grew up in the Anabaptist tradition and thus understand—and appreciate—it from “the inside.” The strengths of the pacifist perspective are multiple and certainly compelling. It is sensitive to the violent tendencies that permeate both human experience in general and American culture in particular. In addition, it recognizes diverse—and in many ways, creative—avenues for political and social action. In the words of Jean Bethke Elshtain, pacifism puts “violence on trial” in that it views social life from the perspective of the potential victim and not the victor.[xxvi] Furthermore, it is keenly sensitive to the distortions of faith that come with an uncritical view of the state that fades into nationalism—a continual problem throughout history and not one that is uniquely American.[xxvii]

Mainstream Christian thinking through the ages takes exception to pacifist pre-commitments at several critically important levels; these criticisms are theological, historical, moral-philosophical, and hermeneutical in nature.[xxviii] One objection to religious pacifism is its failure to make the fundamental moral distinction that exists—supported in Scripture—between shedding innocent blood and shedding any blood. This is seen in the Sixth Commandment, in the post-flood covenant with Noah (Gen. 9), and in the rationale for the cities of refuge (Num. 35, Deut. 19, and Josh. 20). Not all killing is murder. To fail to acknowledge this important distinction not only undermines the common good but can even be said to prepare the ground for totalitarianism.[xxix]

The mainstream of Christian thinking differs with religious pacifists on another critically important front. Politics and guarding the common good (which encompasses a host of civil service vocations) are not a “necessary [or intrinsic] evil” but rather a part of our stewardship in tending all of creation (unless, of course, scripture explicitly condemns particular vocations as intrinsically immoral). Notice that for John the Baptist, in a context of repentance (Luke 3:14), the sin of soldiers is not being soldiers, any more than Zacchaeus’ sin (Luke 19:1-10) was collecting taxes; rather, it was the temptation to be unjust. Notice, too, that two officers in the Roman Legions are paradigms of faith. One is praised by Jesus for his utterly remarkable faith (Matthew 8:5-13), and another is used by God to open Peter’s eyes to God’s purposes (Acts 10 and 11). Significantly, a centurion is the first baptized Gentile. In the New Testament, soldiers or those in authority are never called away from their vocation.[xxx] For this reason Aquinas begins his discussion of war in the Summa by asking “Is it always sinful to wage war?”

At the same time that guarding the common good is a legitimate calling, a moral realism about human nature should cause us to think soberly about the use—and abuse—of power and politics while at the same time preventing us from opting out of political reality altogether in favor of utopian fantasies. This sobriety requires of us participation, action, and moral discernment in a world of limits, estrangements, and partial justice wherein we recognize the provisional nature of all political arrangements. These assumptions about political reality, rooted in Augustinian thinking about the “two cities”—the city of God and the city of man—call us to live “between the times” in a way that takes both citizenships seriously. In refusing to engage in policy and politics, pacifism creates the morally awkward dilemma of keeping its hands clean while unbelievers dirty their hands in the business of maintaining justice.

Yet another qualification needs emphasis which pacifism is inclined to overlook. “Peace” can be unjust and therefore illicit in character. Insofar as bandits, pirates, terrorists, and criminals—in any age and social context—maintain an orbit of “peace” around them in order to flourish, peace must be justly ordered. In the words of Aquinas, “peace is not a virtue, but the fruit of virtue.”[xxxi] Peace and justice are both human goods, but neither is an absolute good. The Christian position, it needs emphasizing, is not “peace at any price.”[xxxii] Mainstream Christianity’s disagreement with pacifism does not simply concern the means of establishing peace; rather, it concerns the nature of that interim worldly peace. Because of its commitment to “non-violence” and consequent refusal to resist evil directly through action, ideological pacifism would seem to bestow upon evil and tyranny an advantage. Michael Walzer worries that pacifism concedes the overrunning of a country or people-group needing defending, something that no government has ever done willingly.[xxxiii]In the words of C.S. Lewis, “If war is ever lawful, then peace is sometimes sinful.”[xxxiv]

Finally, civic peace—i.e., that which guards the common good and allows people to flourish—is not the peace of the eschaton. As Luther is to have famously quipped, if we insist that in the present life the lion lie down with the lamb, the lamb will need constant replacing. The prophetic images of lion and lamb, adder and infant, leopard and goat are intended to be eschatological; it is utopian and fantastic to expect these to be lying together and playing in the present life. Our present obligations concern guarding and justly ordering a temporal peace, not the perfect peace of the city of God.

Love & Justice in Concord: Support for the Thesis

Because the Christian social ethic rests on a bedrock of theological foundations, chief of which is the character of God himself, we would expect to find a mainstream of thinking about charity and justice among the church’s fathers of any era. And indeed we do, both ancient and modern.

Augustine & Aquinas

Augustine is important inter alia because he reminds us of our two citizenships—one in the “city of God,” one in the “city of man.” When push comes to shove, Augustine is very clear in De Civitate Dei that our ultimate allegiance is to the divine city. However, that does not release us from our responsibilities to the city of man, and in that city there is a critical need for ordering society because of the effects of sin. Hence he speaks of the tranquillitas ordinis, the justly-ordered peace. Because of evil and the obligation of Christian love to defend and protect the innocent third party, to not apply what he calls “benevolent harshness” (benigna asperitas)[xxxv] to stop the evildoer is itself to do evil. In Augustine’s “benevolent harshness,” love and justice necessarily merge.

Charity, as Augustine conceives of it, must motivate all that we do, including the application of coercive force. Not the external act but our internal motivation determines the morality of our deeds.[xxxvi] As a social force, this “rightly ordered love”[xxxvii] is foremost concerned with what is good—good for the perpetrator of criminal acts, good for the society which is watching, and good for future/potential offenders.

To read Aquinas’ treatment of both charity and justice in the Summa is instructive. Questions 23-46 of II-II are devoted to the nature of charity, its priorities, its moral dimensions, and its consequences. To the interrogatory, “Is a command to love really necessary?”, Aquinas answers, “Yes”, any moral obligation requires a command, given sin and the human propensity for hatred. In fact, the command to love is implicit in all ten commands of the Decalogue. The virtues, of which caritas is one, are developed habitually and therefore must be both commanded and practiced. As a virtue, then, love for Aquinas is “a principle of action.”[xxxviii]

What is noteworthy in Aquinas’ discussion is the fact that war is contextualized in the middle of his treatment of caritas (Q. 40). Charity and justice meet and guide us in applying coercive force. And one of the three classic criteria for a war to be considered “just’ is right intention. Right intention is measured by the presence of both charity—which desires the best for the neighbor—and justice (Q. 58)—which is protective of the basic rights of the innocent neighbor. Because “justice directs a man in his relations with others,”[xxxix] justice and love meld in Thomistic thought.

Niebuhr and Ramsey

Two Christian thinkers closer to our time share this commitment to prevent love and justice from being disengaged, though in differing ways. Reinhold Niebuhr, as clouds were forming on the European horizon in the 1930s, grew impatient with standard Protestant ethics of his day. In the end, Niebuhr rejected the divorce of love and justice, even when his theological reasoning must be viewed as deficient. (Here I refer to his now famous words, the “impossible possibility,” to describe Jesus’ love ethic.[xl]) Niebuhr believed that “the final law in which all other law is fulfilled is the law of love.” But, he insists, “this law does not abrogate the laws of justice, except as love rises above justice to exceed its demands.”[xli] Tellingly, he writes: “The gospel is something more than the law of love. The gospel deals with the fact that men violate the law of love.”[xlii]

“Christian orthodoxy,” Niebuhr laments (in An Interpretation of Christian Ethics), has “failed to derive any significant politico-moral principles from the law of love… It therefore destroyed a dynamic relationship between the ideal of love and the principles of justice.”[xliii] The result of this divorce, he believes, is tragic: we end up abetting injustice.[xliv] Hence, he lampoons Protestant naïveté on the eve of World War II with a sarcastic lament, suggesting that if only Christians had demonstrated more non-violent love and “if Britain had only been fortunate enough to have produced 30 percent instead of two percent conscientious objectors to military service, [then] Hitler’s heart would have been softened and he would not have dared attack Poland.”[xlv]

One generation closer to us, the noted Princeton ethicist Paul Ramsey insists that “a Christian, impelled by love,” simply “cannot remain aloof…toward the neighbor.”[xlvi] Although Ramsey views love as central, he regularly speaks of “the ethics of obedient love.”[xlvii] Love, Ramsey insists, originates in righteousness and justice.[xlviii] Which is why Jesus’ teaching emphasizes a rule, a kingdom, and not simply love.[xlix]

Neighbor-love is the primary feature of Ramsey’s “obedient” love because it is cognizant of the imago Dei in others. For this reason, in Basic Christian Ethics Ramsey speaks of “a Christian ethic of resistance”[l] and a “preferential ethics of protection”[li] that has the innocent neighbor or third party in view.[lii] Hence, “Love can only do more, it can never do less, than justice requires.”[liii] “[N]o authority on earth,” he writes, can withdraw from charity or justice their inclination to “rescue from dereliction and oppression all whom it is possible to rescue.”[liv] In the end, Ramsey opposed what he called “pure agapism,” which mistakenly assumes that no basic ethical principles other than “the law of love” are valid. There are general rules of practice, as he argues in his important work Deeds and Rules in Christian Ethics.[lv] To his great credit, Ramsey’s theological orientation always had responsible policy in view.[lvi]

Concluding Reflections

In a faithfully Christian and natural-law construal of social ethics, there is to be found a reciprocity and symbiosis—a unity—between charity and justice. Although we might be tempted on occasion to think that the two virtues stand in tension or in conflict, this inclination must be rejected as false, and hence, ethically damaging. Charity flows from goodness, which is in fact no goodness without the leaven of justice.[lvii] Alas, the two stand in true harmony.

Charity, if it is authentic, will respond to human need by looking both to the good of the individual and the common good, always seeking to honor what is just. Justice, if it is truly just, will always seek humane and morally appropriate ways of dealing with human behavior, never losing sight of the fact of human dignity. In preserving the unity of love and justice, we affirm the image of God in all people as moral agents. This affirmation expresses itself not just incidentally but particularly in the realm of retribution. As C.S. Lewis argued against the grain in his day, we punish precisely because humans are moral agents created in the image of God.

The importance of just restitution in affirming human dignity is illustrated forcefully by South African Judge Richard Goldstone, former chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. Goldstone had this to say in an address at the U.S. Holocaust Museum:

The one thing that I have learned in my travels to the former Yugoslavia and…Rwanda and in my own country is that where there have been egregious human rights violations that have been unaccounted for, where there has been no justice, where the victims have not received any acknowledgment, where they have been forgotten, where there’s been amnesia, the effect is a cancer in the society.[lviii]

What is Justice Goldstone saying? He is saying that justice is retributive and restorative, and not one to the exclusion of the other. One thing needing emphasis in our day is this: the process of restoration cannot bypass repayment of the debt. Anselm grasped this in his understanding of atonement, noting, “if sin is neither paid for nor punished, it is subject to no law.”[lix] Justice Goldstone grasps this, too. Christian love does not set aside the need for restitution, payment, or satisfaction of a public debt.[lx] Before he became Pontiff, John Paul II pressed this very argument, in his book Sign of Contradiction, namely, that temporal punishment produces a necessary cleansing and purification from sin.[lxi]

Retribution, understood properly, is a moral entity that serves a civilized culture. It does not stand in opposition to Christian charity or human dignity but rather expresses both when guided by the harmonious melding of justice and charity.

—

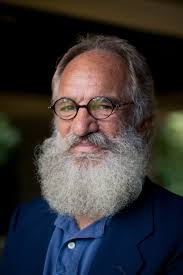

J. Daryl Charlesteaches in the Chattanooga Fellows Program and is an Affiliated Scholar of the John Jay Institute. He is author, co-author or editor of 14 books, including (with Mark David Hall)America’s Wars: A Just War Perspective (University of Notre Dame Press, forthcoming), (with David D. Corey) The Just War Tradition: An Introduction (ISI Books, 2012), (with Timothy J. Demy) War, Peace, and Christianity (Crossway, 2010), and Between Pacifism and Jihad (IVP, 2005).

Image Credit: Justice and Divine Vengeance Pursuing Crime by Pierre-Paul Prud’hon, via Wikimedia Commons.

—

[i] See the opening chapter of her Creed or Chaos? (Sophia Institute Press, rep. 1995).

[ii] Throughout this essay I am using the terms “retribution” and “punishment” interchangeably.

[iii] Hence, the response by Athanasius and Nicea to Arian distortions.

[iv] Hereon see more recently James E. Dolezal, God without Parts: Divine Simplicity and the Metaphysics of God’s Absoluteness (Eugene: Pickwick Publications, 2011).

[v] For example, a proper understanding of the doctrine of atonement, and penal substitution in particular, will refuse to pit an angry, wrathful Father against a loving, merciful Son.

[vi] Summa Theologiae I-II Q. 94.

[vii] C.S. Lewis, “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment,” in W. Hooper, ed., God in the Dock: Essay on Theology and Ethics (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970), 287-300.

[viii] Matt. 5:14-48; 22:37-40; Rom. 13:6-10; James 2:8-11.

[ix] It is the difference between “vigilante justice” and bona fide justice.

[x] Significantly, Jesus does not set aside the concept of lex talionis, which is rooted in Old Testament moral law (Ex. 21:24; Lev. 24:20; Deut. 19:21). His quarrel (see Matt. 5:38-42) is not with the upper and lower limits of justice as per the lex talionis but with the abuse of recompense in his own day – an abuse that appears to have been sanctioned by contemporary rabbinic teaching (“You have heard it said…,” 5:38a).

[xi] City of God 14.14 and Contra Faustum 22.74.

[xii] Mere Christianity (New York: Simon & Schuster, [rep.] 1996), 109.

[xiii] This is true of domestic as well as foreign affairs, of criminal justice as well as prosecuting war. Grotius insisted the “the laws of war and peace” are anchored in the same principles of justice that hold together all domains of civil society (On the Law of War and Peace 2.1.9).

[xiv]Søren Kierkegaard, Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses, trans. H.V. Hong and E.H. Hong (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 56.

[xv] Ibid., 71.

[xvi] Cf. James 2:8.

[xvii] Works of Love, ed. and tr. H.V. and E.H. Hong (New York: Harper & Row, 1962), 345.

[xviii] D.J. Wenneman, “The Role of Love in the Thought of Kant and Kierkegaard” (accessible at https://www.bu.edu/wcp/Papers/Reli/ReliWenn.htm), develops this insight with particular clarity.

[xix] Anders Nygren, Agape and Eros, trans. P.S. Watson (London: SPCK, 1953), 28.

[xx] Ibid., 211-19.

[xxi] Ibid., 61-62, 65-66, 81-91, 105-45, 146-59. The primary biblical components of Nygren’s thesis are Jesus’ reiteration of the “two greatest commandments” (Matt. 22:37-40; Mark 12:29-31), the parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15), and the centrality of “God is love” in Johannine literature.

[xxii] Ibid., 75-80.

[xxiii] James F. Keenan, Moral Wisdom (Lanham/Oxford, U.K.: Rowman& Littlefield, 2004), 14.

[xxiv] As a helpful antidote to this false dichotomy, see the important 1993 papal encyclical of John Paul II, Veritatis Splendor, available online.

[xxv] Admittedly, my choice of contemporary voices has been selective and representative, limited as it is by space and time. Other examples include Edward Collins Vacek, Love, Human and Divine: The Heart of Christian Ethics (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1994); Timothy P. Jackson, The Priority of Love: Christian Charity and Social Justice (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009); and idem, Love Disconsoled: Meditations on Christian Charity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

[xxvi] Jean Bethke Elshtain, Women and War (rev. ed.; Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 123, 132.

[xxvii] At least for a previous generation of “conscientious objectors” like my own father (a Mennonite who performed alternative service in a Veterans Hospital during World War II), it has shown a willingness to sacrifice and count the cost of one’s own convictions. Of course, conscription was the reality of the Second World War, unlike today with soldiering in our culture a voluntary matter, which renders pacifism as “policy” in a wholly different light.

[xxviii] For all the high praise that was showered upon Richard Hays’ The Moral Vision of the New Testament: A Contemporary Introduction to New Testament Ethics (New York: HarperCollins, 1996) following its publication (and the praise was effusive from all corners), Hays’ pacifist reading of the New Testament (chapter 14: “Violence in Defense of Justice”) is exceedingly disappointing at all levels—theologically, historically, moral-philosophically, and hermeneutically. More recently, Nigel Biggar, In Defence of War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), esp. chapters 1 and 2, has subjected Hays’s pacifist reading of scripture to withering—and surely much needed—scrutiny.

[xxix] This important moral has been succinctly emphasized by Elizabeth Anscombe, “War and Murder,” in M.M. Wakin, ed., War, Morality and the Military Profession (Boulder: Westview, 1979), 285-98.

[xxx] In his writings, Anabaptist theologian John Howard Yoder mistakenly asserts that Revelation 13, not Romans 13, is the true portrait of governing authorities. Yoder’s position goes one step further than his Anabaptist forebears; Article 6 of the Schleitheim Confession of 1527, the earliest formal declaration of Anabaptist beliefs, confesses: “The sword is ordained of God outside the perfection of Christ. It punishes and puts to death the wicked, and guards and protects the good. In the Law the sword was ordained for the punishment of the wicked and for their death, and the same (sword) is (now) ordained to be used by the worldly magistrates.” What Schleitheim rejects is that Christians themselves can wield the sword or serve as magistrates.

[xxxi] Summa Theologiae II-II Q. 29.

[xxxii] Therefore, Jesus’ words “Blessed are the peacemakers” need severe qualification.

[xxxiii] Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations (4th ed.; New York: Basic Books, 2006), 329-35.

[xxxiv] “The Conditions for a Just War,” in God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, ed. by Walter Hooper (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970), 326. The moral distinction between a just and an unjust peace highlights the logical conclusion and moral obtuseness of Gandhi’s “non-violence.” Gandhi’s advice to European Jews who were being delivered to extermination camps by the Nazis was to commit suicide in order to get the world’s attention and speak to the conscience of nations. (See in this regard George Orwell, “Reflections on Gandhi,” Partisan Review 16, no. 1 [1949]: 85-92, accessible online as well at http://www.online-literature.com/orwell/898/.) Notice the contradiction here: whereas violence toward others was viewed by Gandhi as immoral, violence directed toward the self was to be countenanced. One is justified in arguing that Gandhi’s “pacifism” was only possible in relatively free nations like India, a British colony, and not in totalitarian societies like the Soviet Union or Nazi Germany.

[xxxv] Epistle 138, “To Marcellinus.”

[xxxvi] The City of God 14.9.

[xxxvii] All that was created is “good,” for Augustine; however, when our loves are not rightly ordered, the ultimate good is violated (City of God 15.22).

[xxxviii] Summa Theologiae II-II Q. 23-46, 58; cf. also Commentary on Nicomachean Ethics, Lectures IV-VI.

[xxxix] Ibid. II-II Q. 58, a. 9, r. 3.

[xl] Reinhold Niebuhr, Christianity and Power Politics (New York: Scribner’s, 1940), 3. In An Interpretation of Christian Ethics (Cleveland and New York: Meridian, 1956 [repr.]), 134, Niebuhr writes, “The ideal possibility is really an impossibility.” What Niebuhr called “Christian idealism” creates an illusion; what is needed, rather, is a “Christian realism” (D. B. Robertson, ed., Love and Justice: Selections from the Shorter Writings of Reinhold Niebuhr [Philadelphia: Westminster, 1992], 41-43). A useful corrective to Niebuhr’s deficient theology is offered by Paul Ramsey in “Love and Law,” in Charles W. Kegley and Robert W. Bretall, eds., Reinhold Niebuhr: His Religious, Social and Political Thought (New York: Macmillan, 1961), 79-123.

[xli] Love and Justice, 25.

[xlii] Christianity and Power Politics, 18 (emphasis added).

[xliii] An Interpretation of Christian Ethics, 131.

[xliv] Ibid., 136.

[xlv] Reinhold Niebuhr, Christianity and Power Politics, 6.

[xlvi] Paul Ramsey, Basic Christian Ethics (New York: Scribner’s, 1950), 345-46.

[xlvii] Ibid., xvii (emphasis added).

[xlviii] Ibid., 367.

[xlix] Ibid., 24-35.

[l] Ibid., 171-84.

[li] Ibid., 166-71.

[lii] In this vein, Ramsey takes Jesus’ teaching on “turning the other cheek” in the Sermon on the Mount and extrapolates, noting that Jesus does not say, If someone strikes your neighbor on the right cheek, turn to his aggressor the other as well (170-71).

[liii] Ibid., 347-48, herewith citing Emil Brunner, Justice and the Social Order (New York: Harpers, 1945), 129.

[liv] Paul Ramsey, The Just War: Force and Political Responsibility (repr.; Lanham: Rowman& Littlefield, 2002), 35-6.

[lv] Paul Ramsey, Deeds and Rules in Christian Ethics (New York: Scribner’s, 1967).

[lvi] Despite the volume’s sensitivity to the divorce—theoretically and practically—of justice and charity, Nicholas Woltertorff’s Justice in Love (Grand Rapids/Cambridge, UK: Eerdmans, 2011) is remarkable for its inattention to the work of Ramsey. An additional fundamental weakness of Wolterstorff’s volume is its deficient understanding of the relationship between punishment and forgiveness and its rejection of retributive justice and restitution, which Wolterstorff fails to distinguish from revenge. I have evaluated Wolterstorff’s book at length in a review essay that appeared in Spring 2013 issue of the Journal of Church & State.

[lvii] So Anselm, Proslogion 9.60.

[lviii] Richard Goldstone, “War Crimes: When Amnesia Causes Cancer,” Washington Post (February 2, 1997), C4.

[lix] Anselm, Cur Deus Homo 1.12.218.

[lx] Recall the example of Zacchaeus, who paid back four times the debt he owed because of tax fraud (Luke 19:1-10).

[lxi] Karol Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II), Sign of Contradiction (New York: Seabury, 1979), 166-69.