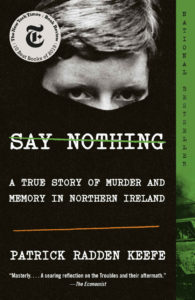

At roughly 7:00 one evening in early December 1972, the children of Jean McConville answered the door to their home at Divis Flats in Belfast, Northern Ireland. A gang of men and women, most of whom concealed their faces, then entered and abducted their mother. Because some of the assailants did not wear masks and addressed them by name, the children realized that these intruders were not all strangers, but included their neighbors. The ten soon-to-be-orphans never again saw Jean, a 38-year-old widow who had grown up in a Protestant family and whose Catholic husband died from cancer the previous January. So begins Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland.

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (Provos) admitted after the Troubles to murdering and disappearing McConville, but the organization insisted that she had been an informant for the British. Even if she admitted to working for the army while being tortured, this explanation lacks evidence and is unconvincing based on Keefe’s narrative—not least because a widowed, suicidal, and medically numbed mother of ten could probably not gather worthwhile intelligence. In contrast, her children remember how one evening after a gunfight in Divis Flats, McConville comforted and prayed over a wounded British soldier. The next morning graffiti on their door read, “Brit Lover.” Animosity from their neighbors grew thereafter. Friendless, the children faced beatings and harassment outside their home, and their two dogs were found dead at the bottom of a garbage chute. Evidence might suggest McConville could have been an informant and consequently liable for execution according to the IRA, but nationalist republican fervor and ethnic animosity appear to be the most likely motivation.

While the war crime and mystery of Jean McConville’s disappearance is the main plot in Say Nothing, Keefe describes the broader story of the IRA members responsible for the murder. His narrative history therefore offers a wide historical sweep of the Troubles, from the late 1960s through the Good Friday Agreement and until more recently. This portrayal emphasizes the activities, crimes, and terrorism of the Provos without much discussion of similar incidents by loyalist paramilitary organizations, but it does include some crimes by the British state.

One key actor is Dolours Price, a convicted IRA bomber who admitted in an interview before her death in 2013 to participating in McConville’s murder. Another is Brendan Hughes, who gave a secret oral history about his activity in the IRA to researchers from Boston College. Both Price and Hughes said Gerry Adams was the IRA leader who ordered the disappearance. Adams, who served as president of Sinn Féin from 1983 to 2018 and was a central figure in the negotiations that led to the Good Friday Agreement, denies these claims and says the two resented the peace deal that kept Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom. Moreover, he has long insisted that he was never a member of the IRA and thus could not have been a leader to order anyone’s disappearance. Yet opinion polls show that even a majority Sinn Féin voters believe he lies when denying his participation in the IRA. Though the British government never had enough evidence to convict him of being a paramilitary member or for ordering McConville’s disappearance, Say Nothing weakens Sinn Féin mythmaking and leaves a strong impression that Adams belongs in prison, not jet setting around the world, meeting American presidents, attending a US presidential inauguration as a congressman’s guest, or being considered as a possible recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. Yet as some voices in Say Nothing attest, Adams made Northern Ireland’s peace feasible.

The story behind Say Nothing is captivating enough to serve as the basis of a gritty HBO-style miniseries with three or four seasons full of violence, espionage, infidelity, and mystery. Keefe presents a complicated history coherently, offering readers unfamiliar with the Troubles a good review, and his narration keeps readers engaged. Just as political writers should read P.W. Singer and August Cole’s Ghost Fleet and Burn-In to understand how those books communicate wonky ideas in a way that makes readers want to finish, writers should read Keefe’s Say Nothing to learn from how it presents history. Many academics and historians do excellent research and writing. Few can turn 450 pages into a bingeable read like Keefe.

Of note for regular Providence readers, Say Nothing briefly mentions a topic they should recognize: moral injury. In Marc LiVecche’s words, this is “a combat trauma that occurs when one does—or believes they have done—something that violates a deeply held moral commitment.” Keefe makes the case that Dolours Price felt this trauma because the Good Friday Agreement meant the whole of Ireland would not unify, her ethical justification for killings, war crimes, and terrorism. She regretted how the conflict ended and said in one interview, “I would not have missed a good breakfast for what Sinn Féin achieved.” Her moral injury makes sense because when people use ends-justify-the-means logic, the means become intolerable when the ends become improbable. Whereas LiVecche often writes on how soldiers fighting in a just war using just means should not feel moral injury, Price arguably deserved to feel regret and guilt. Even if the IRA achieved its aims, the just war tradition would not condone its actions. Yet through the Christian doctrine of forgiveness, the church still has a message for those who suffer moral injury, whether deserved or undeserved.

The IRA actions that troubled Price and others appear especially senseless not just because the organization never achieved its aim, but because examining other movements suggests nonviolent strategies could have achieved civil rights for Catholics more effectively. Unification with the Republic of Ireland may have been just as likely, if not more so, without destroying so many lives. Price’s story in Say Nothing begins with a civil rights march that ended with a violent loyalist attack Burntollet Bridge in January 1969. The scene is reminiscent of when state troopers and a mob attacked nonviolent protestors on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, in March 1965. Amongst other violence at the time, the Burntollet Bridge attack was a pivotal moment for republicans like Price, who rejected nonviolence and joined the IRA. Given how many of their families previously fought with the IRA, the decision is not surprising. But it is tragic when compared to what the Civil Rights Movement achieved in America without such violence while the Black community endured segregation, state opposition, lynchings, terrorism, bombings, murders, disenfranchisement, and more. Forty-four years after the attack on the Selma bridge, a Black man became president; more than 50 years after the Burntollet Bridge attack, Ulster is still British. Keefe does not make much of the comparison, but for this reviewer the example of nonviolent African Americans, although occurring in a different environment, served as a constant contrast while reading the book.

Numbers and statistics can desensitize students of war to real tragedy. But Keefe’s focus on Jean McConville’s murder in Say Nothing gives readers a detailed examination of the Troubles while reminding them of the victims. In hindsight the violence appears exceptionally senseless, but studying the conflict in Northern Ireland can offer many lessons—including on moral injury, global politics, counterinsurgency, justice, and peace.