Court-packing means passing legislation to expand a court in order to shift its approach toward disputed policy initiatives. A plan to pack the US Supreme Court is popular among progressives, justified as a “defensive measure” against the Republican Party’s recent success in installing justices. The fact that many in Congress, as well as large segments of the American electorate and commentariat, consider court-packing a morally legitimate political tactic reveals serious deficits in our society’s understanding of and respect for the rule of law, America’s founding principles, and justice itself. What is more, it shows disrespect for the very idea of truth.

Court-packing and tampering have typically been tactics of authoritarian or just heavy-handed regimes. In Argentina, populist Juan Perón impeached judges who stood in his way, and decades later, Argentine President Carlos Menem added four justices to the Supreme Court to clear away legal obstructions to his rightist economic program. In recent years, governments in Poland, Hungary, and Turkey have manipulated high courts in ways that have been denounced as threatening to the rule of law by many in the international legal community.

In 1937, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt attempted to pack a divided Supreme Court in order to reverse its findings that parts of New Deal legislation were unconstitutional. His proposed Judicial Procedures Reform Bill would have permitted the president to appoint as many as six additional justices for every member of the Court over age 70.

Senators from Roosevelt’s own Democrat Party thwarted the initiative. Their resistance was backstopped by broad public opposition led by both opponents of the New Deal and some prominent Democrats who organized the National Committee to Uphold Constitutional Government. According to a 1965 study by Richard Polenberg in the Journal of American History, the group distributed materials opposing Roosevelt’s court-packing legislation to almost half a million lawyers, doctors, business leaders, and members of the clergy.[i] Public sentiment was divided, but opponents articulated a principled rejection of tampering with the Supreme Court in order to push through social legislation, even though many opponents of the measure personally favored it.

Independent Courts

Of course, had he been successful, President Roosevelt would have appointed justices whom he knew would rule in his favor. Roosevelt would clearly not have appointed independent justices, but rather those ready to rule on the basis of a priori, ideologically driven policy preferences. His court-packing attempt was thus a challenge to the ideal of an independent judiciary. In the Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton wrote, “The complete independence of the courts of justice is particularly essential in a limited constitution.” Without independent courts, there can be no fair trials or equality before the law, which are fundamental to civil and human rights.

But is it possible for judges to be “independent”? What does that really mean?

It means first that courts are independent of other branches of government. A court that has been packed has in effect been taken over by other branches of government and brought under their control. Court-packing is thus a fundamental assault on the separation of powers, which was designed by the Framers of the Constitution to constrain governmental power.

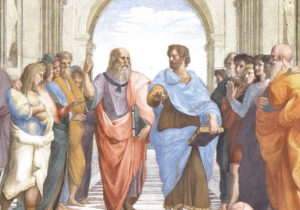

An independent judiciary also means that judges “enforce the law and resolve disputes without regard to the power and preferences of the parties appearing before them.”[ii] The judge must be independent of the executive and legislative branches, but also of his or her own biases. Indeed, images of Lady Justice show her blindfolded, unable even to see whoever is on trial. The blindfold deprives her of sensory capacity so as to prevent the engagement of her prejudices, to thwart her emotional processes. But while she is deprived of sight, since ancient Greek times she has been depicted with an instrument to enhance her powers: a set of scales to weigh evidence—a neutral instrument capable of objective measurement. In effect, she is not a normal person, but one both deprived of personal feelings and assisted by technology, a machine that runs on reason. Her cases are decided by reason itself.

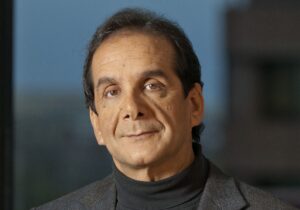

Lady Justice is an ideal; reality tells a different story. The issue of bias is perennial, typically emerging when nominees for Supreme Court justices and lower court judges are examined. During his infamous and unsuccessful Senate confirmation hearings in 1987, Judge Robert Bork made balanced and measured observations on this issue. The metaphorical blindfold worn by Lady Justice requires moral self-discipline: “We all see the world and facts through a lens composed of our morality and understanding,” he said. But despite this “inevitable bias,” judges can and should strive for objectivity by a “self-conscious” effort to keep biases out. Bork contrasted this approach with other self-conscious and purposeful efforts to use the law to serve a judge’s political agenda, that is, so-called “judicial activism,” which he said had become the preferred option among legal academics. Bork worried that as a result, courts were setting social agendas, usurping the role of citizens acting through legislative representatives, and thus weakening democracy itself.

Judicial Criteria

Since Bork was “borked” in a shameful Senate Judiciary Committee hearing, his concerns have become even more acute problems in recent years. Judges are too often evaluated not on the integrity of their approach toward their job, but rather on the basis of their putative political views. The fundamental question is whether judges see their role as interpreting the law, and, in the case of the Supreme Court, deciding if legislation is consistent with the Constitution as it was written, or whether they see the Constitution as a “living document” that can be interpreted to permit the president and Congress to intervene in society and private life as they might wish, seeing the law, itself, as a political instrument, and legal practice as a form of politics. Extreme forms of this latter tendency may be observed in the utter, nihilistic cynicism of totalitarian approaches toward constitutional law. The Soviet communists ruled on the basis of the overt subordination of “bourgeois law” to ideology. The constitutions of North Korea and some other totalitarian states guarantee individual freedoms, including religious freedom, so long as they are permitted by the law, which violates the very concept of universal rights being prior to, and above the laws of the state.

It is not a surprise that “originalist” judges tend toward conservatism in the sense of favoring less government intervention, and more freedom for individuals in civil society. Most agree that this was the intent of America’s Founders, and that “living constitution” types interpret the document to allow the government, through wealth-redistribution schemes, to try to solve social problems and inequalities. But stereotypical “liberal” and “conservative” approaches to complex social questions mushrooming up in our society do not necessarily track with this polarity. The threat to the idea of an independent judiciary comes not only from leftists seeking to nullify constitutionalist opposition to expansive government programs; it comes as well from social conservatives who demand that originalist judges tow their line. Justices Neil Gorsuch and John Roberts, for example, in the Bostock case,[iii] disappointed and enraged social conservatives by joining a majority of the Court in extending the Civil Rights Act to include protections on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

At the beginning of the first Trump-Biden presidential debate on September 29, 2020, Joe Biden explained his objection to the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court in part because “she thinks that the Affordable Care Act is not constitutional.” But Barrett, as a Supreme Court justice, surprised those who assumed that her thinking would be confined within the deep ideological ruts and group-think that have retarded the political reasoning-power of Americans. Indeed, she has already defied the orthodox secular bigotry embedded in Senator Dianne Feinstein’s now-notorious claim that her putative Catholic dogma lived “loudly within” her, a claim that she was incapable of unbiased judgment. American media seemed shocked when Barrett and other “Trump justices” upheld Obamacare, ruling that a challenge lacked constitutionality. Perhaps these justices do not embrace the ideological implications of the law, but they put their own views aside to rule on the law’s constitutionality.

Independent Thinking

Americans today tend not to trust judges who say they will keep their biases out of the courtroom, but also attack them when they do. Intellectually saturated with social scientific determinism, we tend not to believe or trust that independent thought is even possible, not to mention necessary or good. But civil society, as a counter-balance to state power and its inevitable abuses, requires free-thinking individuals, detached from and able to withstand pressure to conform to partisan expectations. To maintain the clarity and integrity of fundamental moral principles requires a form of self-nullification or self-abnegation that transcends identity politics and self-concern.

That is what Lady’s Justice’s blindfold symbolizes, and civic courage, so essential in a democracy, requires that citizens not only respect this quality in the judiciary, but partake of it themselves in the process of self-rule. Not only judges, but citizens need to be free of moral domination by others, and by group loyalties. Citizens need to seek freedom from their passions and prejudices in making political choices. But challenges to this ideal of individual rational detachment are stronger today than in past eras, largely because of the very “connectedness” that is considered a virtue in the Internet Age. The seamless barrage of short, sharp, undifferentiated, and often demagogic messages penetrates our thinking, driving wedges into any foundation of reason and logic that has survived despite politicized educational experiences. A tribal or feudal, pre-modern form of thinking has reemerged as a result of modern technology, a form of thinking where ascriptive identities once again trump character and achievement. Media and popular dramas are saturated with sentimentalism; what seems to be important to Americans is how they “feel” about things. But a functioning democracy—which is the only system that can protect individual liberty and ensure justice in a pluralistic, multi-ethnic society—requires citizens able and ready to think, not simply be driven by sentiments; citizens ready to weigh currents of conformism in contemporary thought against universally applicable principles. Given problems evident in American democracy today, meeting those intellectual requirements of democracy should have top priority.

[i] Richard Polenberg, “The National Committee to Uphold Constitutional Government, 1937–1941”, The Journal of American History, Vol. 52, No. 3 (1965-12), pp 582–98.

[ii] George Tridimas , “Independent Judiciary,” in Encyclopedia of Law and Economics (Springer Science+Business Media, New York, 2014).

[iii] Bostock v. Clayton County, Altitude Express Inc. v. Zarda, and R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.