Joseph Loconte’s lecture at Christianity & National Security 2023.

Joseph Loconte discusses C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and their perspectives on war. The following is a transcript of the lecture.

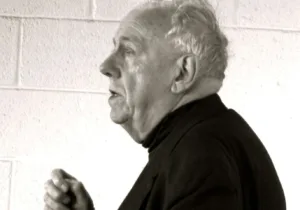

Thank you, Paul Miller, and thank you all again for being such an attentive audience. And we are now prepared for our final speaker, who is also perhaps our most passionate speaker. Uh, Dr. Joseph Loconte, formerly of King’s College, now with New College in… uh, Florida. Prolific writer, author, expert on C.S. Lewis and uh… who’s our other favorite author… J.R.R. Tolkien. So he will interg… you uh… entertain you, regale you, impress you, uh, for the next forty five minutes, uh, to an hour.

We will conclude by 5:00 at the latest, and as we mentioned earlier, uh, for those of you who are so disposed, there will be Chick-fil-A available back at the IRD office for dinner. But that’s not uh… For students, for students so… but not obligatory. So if you have a taste for finer cuisine you’re welcome to seek that out anywhere here in downtown D.C. Otherwise, we’ll see you tomorrow morning, here. The program beginning at 9:00 AM, but breakfast will be available here starting at 8:00 AM. Joseph Loconte, thanks for being here.

Thank you Mark, thank you everybody. Can you hear me back there in the bleacher seats? Alright. You know, I’m supposed to talk here about Tolkien and Lewis on war in Western civilization but… uh, uh, you know that Mike Johnson was elected as the Speaker of the House, and I heard this morning that he has abdicated the position. They’ve asked me to step in as the interim Speaker… That was a joke, that was a joke.

But that’s how chaotic the world is right now. Uh, conservatives and liberals both in a state of moral chaos, it seems to me. And the point of that is we’re awash in lies. We are a society awash in lies, and we have… in a… we’ve been down kind of this road before in some ways. And the encouraging thing is that two IRD individuals, two great friends, two amazing authors, push back. They push back.

So let’s get into it. Over a century ago, the National Peace Council of Great Britain, a group of religious and secular peace organizations, issued this proclamation about a century ago: “Peace, the babe of the 19th Century is the strong youth of the 20th Century because war, the product of anarchy and fear is passing away under the growing and persistent pressure of world… world organization.”

Economic necessity and that change of spirit, the Zeitgeist of the age, the National Peace Council made that prediction in its 1914 edition of the Peace Yearbook. Within a matter of weeks, the nations of the earth became embroiled in a global conflict; the First World War, the most destructive, dehumanizing war the world had ever seen.

So… so much for delusions, liberal delusions in particular, about human nature and the nature of human conflict. Two of the most beloved Christian authors of the last century, J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, they were both thrust into the jaws of the industrial slaughterhouse of the First World War. Both served as second lieutenants with the British Expeditionary Force in France, and remember, friends, what the soldiers on the Western Front had to do to endure the mortars, the machine guns, the tanks, the poison gas, the flamethrowers, the barb wire, the thousands of miles of trenches, and the mud.

Never before had technology and science so conspired to destroy both man and nature. When it was all over, wrote Winston Churchill “torture and cannibalism were the only expedience that the civilized, scientific, and Christian states had been able to deny themselves.”

Well, Clive Staples Lewis, C.S. Lewis, was injured, nearly killed, by a mortar shell that obliterated his sergeant standing nearby. Most of his friends perished in the war. He wrote to his father from his hospital bed. I could sit down and cry over the whole business… J.R.R. Tolkien fought at the Battle of the Somme, one of the fiercest concentrations of killing in the history of human combat. On the opening day of the Somme offense of July 1, 1916, the British lost over 19,000 men on a single day. 19,00. It remains the single deadliest day in British military history, and you think about it, that’s a lot of military history.

Listen. To Tolkien, one has indeed personally to come under the shadow of war to feel its full oppression. He said, “to be caught up in youth by 1914 was no less hideous in experience than to be involved in 1939 and the following years.” He says “all but one of my close friends were dead.” Now these men had no romantic illusions about the horror and the human cost of war. “We remember the trenches too well,” Lewis said, and yet both men used their experience of combat, yes the experience of combat, to engage their imaginations.

They list the hardships of war as a crucible for moral and spiritual growth. Let me understcore that. The crucible of war, war as a path to moral and spiritual growth. When Lewis arrived in France in 1917, he was an atheist. He was quite literally an atheist in a foxhole, and his poetry during this time… It just rages against the silent and uncaring Heaven. There’s a few lines from Lewis: “Come let us curse our master, ere we die for all our hopes and endless ruin lie. The good is dead, let us curse God most high.” That’s C.S. Lewis.

In 1917, Tolkien said his love for fantasy was quote, “quickened to full life by war.” Quickened to life by war. He began writing the early parts of his mythology about Middle Earth when he was in the trenches, as he said, by candlelight, intense, even some down in dugouts under shellfire… It’s during this period that he conceives the story of the fall of Gondor, the tale of how the Elven city of Gondor is betrayed into the hands of Mordor.

Listen to a few lines from that story: “there at the end of a weary night in the gray of dawn, he saw a land defiled and desolate. The trees were burned or uprooted. All, now, was but a welter of frozen mires, and a reek of decay like a foul mist upon the ground.” What does that sound like? Sounds like no man’s land, doesn’t it? It France, Tolkien called this the first real story of his imaginary world. He’s talking about the war for Middle Earth.

Friends, he’s laying a foundation for his great epic work, but it’s not only the experience of the trenches that gave these men a sober view of war. Twenty years after the end of the first World War, Tolkien and Lewis have to endure a second World War, and they face the onset of that conflict with Great Britain near the center of it, with a sense of revulsion and foreboding. And Lewis writes to his friend Dom Griffith April 29 1938 “I have… I’ve been in considerable trouble over the present danger of war twice in one life, and then, to find how little I have grown in fortitude despite my conversion.” He writes his friend again October 5th, 1938: “I was terrified to find how terrified I was by the crisis. Pray for me for courage.” All right, historians in our ranks, what crisis is he talking about? He’s writing October 5th 1938, what’s the crisis? Say again… Crisis… Keep talking, what’s the Sudetenland crisis? About what?

Was it Germany invading Czechoslovakia, or part of… part of Czechoslovakia? He’s talking about the Munich crisis. Right. You’re right. When Hitler demands a portion of Czechoslovakia in exchange for the promise of peace, right? The Munich Pact, signed September 30th, just a week before goes down in history as a desperate and feudal act of appeasement. It will not prevent the second World War. So, for Tolkien and Lewis, their personal and professional lives, think about it.

They’re bracketed by war, by the most devastating wars in human history, when Western civilization itself seemed to sit on the edge of a knife, and yet the experience of war… it deepened their spiritual quest and it shaped their literary imagination. That’s my thesis. Out of war came a great friendship, and out of their friendship came their great imaginative works, stories about the conflict between good and evil, about heroism, about sacrifice for a noble cause, war, friendship, and imagination. That’s the big picture: war, friendship, and imagination in the shadow of war.

Tolkien creates the Hobbit, the Lord of Rings… Lewis earns fame for the Chronicles of Narnia, the Screwtape Letters, the Space Trilogy, Mere Christianity… conflict… the conflict between light and darkness is center stage in each of these stories. So what was their approach to war? Well, many veterans of World War I, they wrote blistering anti-war poetry and novels in the 1920s and ‘30s, right? Goodbye to all that Farewell to Arms.

An entire generation of Christian ministers vowed to never support Britain in another war. The students at the Oxford Union Society, this is the cream of the crop of British society, right? The students of the Oxford Union Society voted in February 1933 quote “this house will under no circumstances fight for its king and country.” Historians in our ranks, what’s the significance of that time period? February 1933, this house will under no circumstance fight for it’s king and country… What’s happened just a week before that vote? Hitler is chancellor of Germany. Bad timing for that vote… Sends the wrong message, doesn’t it?

There was a cultural lurch toward pacifism, toward pacifism, and both authors, Tolkien and Lewis resist it. Tolkien repeatedly decried quote “the utter stupid waste of war,” on the one hand, but acknowledged it’ll be necessary to face in an evil world. C.S. Lewis, writing in 1944, put it this way: “We know from this experience of the last 20 years…” think back now, 1944, 1920s, “We know from this experience of the last 20 years that a terrified and angry pacifism is one of the roads that leads to war.”

Well, both men fought honorably in World War I, and they’re part of the home guard during the Second World War in addition to their life experiences. What shapes their approach to war? Well they were both educated in the literary canon of Western Civilization, as I believe many of you young people are at your colleges as well, right? A humanities core… Three cheers for the humanities!

They were both educated in the canon of the West, the literary canon: Homer, Virgil, Dante, Milton… Remember those lines from Paradise Lost: “Peace is despaired, for who can think submission war?” Then war, open or understood, must be resolved. Lewis said that outside of the Bible, outside of the Bible, Virgil’s Aeneid had the greatest impact on his professional career. Think about that. C.S. Lewis. Virgil’s Aeneid had the greatest impact on his professional life. Makes you want to go and maybe read the Aeneid, doesn’t it? Maybe.

Um, the Aeneid has been described by one scholar as quote “the single most influential literary work of European civilization for the better part of two millennia.” What is it, friends? It’s a way story. It’s a war story about origins. The founding myth of ancient Rome, written by Rome’s greatest poet when his nation was in the throws of an identity crisis. The classical scholar at Reyes says that, uh, Lewis, his views about Lewis and the Aeneid… This is the scholar Reyes on Lewis… For Lewis, a veteran of the First World War, the beauty and fascination of Virgil’s poem laying… it’s an… in his expression of waste and loss, what affected him most was Virgil’s need to depict the tragedy within War. I think that’s partially right. The human tragedy within war.

It wasn’t only the sense of loss and tragedy that moved him. He wrote a letter to his friend Dorothy Seers dated December 29th, 1946. Here’s what he said, a little insight: “I’ve just reread the Aeneid again,” he didn’t know how many times he’d read it. “I’ve just reread it again. The effect is one of the immanent costliness of a vocation combined with a complete conviction that is worth it.”

That’s a line we’re thinking about, friends. Especially young people. The costs of a vocation… a vocation combined with a complete conviction. It is worth it. Tolkien expressed the same kind of appreciation for Beowulf.

Beowulf, considered the greatest surviving Old English poem, one of the most important works of Western literature. The story of a Scandinavian warrior battling the forces of evil, right? Beowulf… he captured Tolkien’s imagination when he was a young man. He studied it. He translated it. He lectured on it for decades. As Tolkien described it in his 1936 lecture, Beowulf “is the story of men caught in the chains of circumstance or their own character, torn between duties equally sacred, dying with their backs to the wall.”

Well in the story, Beowulf defeats the demon Grindel, Grindel’s mother, and a fearsome dragon, but at the cost of his own life. Tolkien was fascinated by these tales with their portrayal of what? The persistence of wickedness, the value of heroic sacrifice for a heroic cause. Listen to Tolkien, a few lines in his appreciation for this poem: “For the dragon bears witness to the power and danger and malice that men find in the world,” he said. And the dragon now, the dragon now bears witness also to the wit and the courage and finally to the luck of grace that men have shown in their adventures – not all men, and only a few men greatly. “Dragons,” he says, “are the final test of heroes.” Dragons are the final test of heroes. So on the one hand neither Tolkien nor Lewis were more warmongers. They were not warmongers. They were not tempted to jingoism or militant nationalism. On the other hand, they reject the moral cynicism of the 1920s and 30s.

The watch word of the age… friends, after the first World War, if you put it down in one word, disillusionment. A little bit like what a lot of… what a lot of young people have felt about the inconclusive wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Disillusionment… the disillusionment of the postwar generation finds an outlet, friends, in literature, in the arts, in philosophy, science, politics, and religion. Just think about some of the titles of book titles being published in the years after the first World War.

I got a lot of these books on my shelf. I’ll just rattle off some titles starting from around 1920. The End of the World: Social Decay and Degeneration, uh, Oswell Spangler, The Decline of the West, the Decay of Capitalist Civilization, the Twilight of the White Races, Will Civilization Crash?, the Problem of Decadence, and W.H. Ordin’s the Dance of Death. How about that? For Loconte book of the month club? The Dance of Death. Come on in, free coffee and donuts, right? You get the point. You get the mood, the outlook.

To many of the best and brightest, Christianity now lacks an explanatory power. It can’t answer for its role in the remorseless violence unleashed by the supposedly Christian nations of Europe. And yet, Tolkien and Lewis resist the intellectual currents of the day. They don’t get swept up in them. The two men first met at Oxford 1926, and soon become the best of friends. In 1936, they decide to take on the literary establishment. Uh, Lewis had a nickname for Tolkien. He called him Tollers, right? They’re sitting down over lunch, I think, at the Eastgate hotel and he says “there’s… there’s too little of what we really like in stories. I’m afraid we shall have to write some ourselves.” And that’s what they do.

Tolkien publishes The Hobbit in 1937, starts working, working on the Lord of the Rings. Lewis writes Out of the Silent Planet, the first of the Space Trilogy. Both authors navigate between extremes, don’t they? Between militarism and pacifism, between cynicism and utopianism. They carry no illusions about war because they had no illusions about the problem of evil, the tragedy of the human condition, because of man’s fall from grace.

This is the subtext for Lewis’s Space Trilogy as well as the Chronicles, and where a White Witch… She’s got all of Narnia under her thumbs. She makes it always winter. Always winter and never Christmas. Welcome to Washington, D.C., I’m looking for an exit strategy from D.C. Just so you know, looking for an exit strategy, remember the Lord of the Rings: the words of Elron at the Council of Elron. And the elves deemed that evil was ended forever and it was not. So you see, this is in Tolkien’s children’s story.

The Hobbit – how many have read the Hobbit by the way? Just curious. Oh, we got some Hobbits out there. Terrific. All right. Listen to how Tolkien describes the goblins in the story: “Now, goblins are cruel, wicked, bad-hearted. They make no beautiful things, but they make many clever ones. Hammers, axes, swords, daggers, pickaxes, tongs, and also instruments of torture. They make them very well. It is not unlikely that they invented some of the machines that have since troubled the world, especially the ingenious devices for killing large numbers of people at once, for wheels and engines and explosions always delighted them.”

What does that sound like? Sounds like the industrial slaughter of the First World War, the abuse of science and technology. And what do we make of the ring in the Lord of the Rings, friends? The… the battle between Mordor and Middle Earth is called the War of the Ring. Why go to war over a ring? Well, we all know, spoiler alert, the ring gives you the ability to make yourselves invisible, of course, and whoever possesses the One Ring controls all of the others. “One right to rule them all.” One ring to find them, one ring to bring them all, and in the darkness bind them, my precious. In the 1950s at the start of the gold… the Cold War, many people assume now this: Tolkien has finally published the Lord of the Rings, been working on it for thirteen years, in the early 1950s. Many people assume that the ring is a symbol of atomic power. Sounds plausible, maybe. Tolkien sets them straight, but of course, my story is not an allegory of atomic power but of power, he says, exerted for domination.

He has just told us what the Lord of the Rings is about. Power exerted for domination. Think about the world. He’s just lived through the 1920s and 30s and 40s. The geopolitical realities, the ring as the embodiment of the will to power. The desire to exploit, to dominate, control the lives of others. They have a ringside seat to this, friends, in Great Britain in the 1930s and 40s.

The National Peace Council of 1914 claimed that war was quote “the product of anarchy and fear.” I’m afraid that today… today’s progressive elites and some friends on the right talk as if war could be eliminated through arms control agreements of international treaties or spread of democracy or the global distribution of wealth or reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Modern liberalism will not face honestly the problem of will to power.

Lewis tackles this theme directly in his essay “Why I Am Not A Pacifist.” I commend it all to you. It hasn’t already been discussed here at this… at this conference. He challenges the claim that wars never do any good. Here’s a few lines from Lewis: “It’s certain that a whole nation cannot be prevented from taking what it wants, except by war. It is almost equally certain that the absorption of certain societies by certain other societies is a greater evil.” He goes on. “The doctrine that war is always a great evil seems to imply a materialist ethic, a belief that death and pain are the greatest evils. But I don’t think they are.”

We could point out that the Ukrainian people represented by their President Vladimir Zelensky would probably agree with Lewis. This is what Zelensky said just before Russia invaded his country: “if we come under attack,” he said, “if we face an attempt to take away our country, our freedom, our lives, and the lives of our children, we will defend ourselves. When you attack us, you will see our faces, not our backs, but our faces.”

Sometimes war is a tragic necessity. I emphasize the word tragic, this is a major theme of the works in Tolkien and Lewis. Now why? What’s the purpose of war? We’ve heard some of this from our previous speaker. What good could it achieve? From the Lord of the Rings, a few lines: Faramir, the captain of Gondor, remember what he says: “war must be while we defend our lives against a destroyer who would devour all, but I don’t love the bright sword for its sharpness nor the arrow for its swiftness, nor the warrior for his glory… Glory. I love only that which they defend.”

I love only that which they defend. War has a moral necessity to protect the innocent from great harm. To preserve human freedom. To defend civilization against barbarism. And friends, we know now, oh we’ve been reminded what barbarism is haven’t we?

We’ve seen in recent weeks in the savage attacks by Hamas on Israeli citizens: men, women, children, infants slaughtered in an orgy of sadistic violence. This is the moral necessity of war. The moral core of the Christian just war tradition: protect the innocent from barbarism. Well, Tolkien and Lewis wrote epic fantasy. They revived the medieval concept of the heroic quest. The heroic quest, Tolkien said that when he read a medieval work, it stirred him to produce a modern work in the same tradition. And remember what Lewis does in the Chronicles of Narnia.

Narnia is seen as a realm of what? Kings and queens. Where a code of honor holds sway. Where knighthood is won or lost on the field of battle. Now, was this just medieval nostalgia? Nostalgia… many people assume that fantasy writers like Tolkien are… they’re people who are just trying to evade the bitter realities of life.

Fantasy is escapism but what if the experience of two world wars had the opposite effect on these authors? Maybe they weren’t trying to escape reality at all. Maybe they were trying to help us understand it and to face it with hope and resilience. Listen to a few lines from Lewis: “Since it’s so likely that children will meet cruel enemies, let them at least have heard of brave knights and heroic courage.”

Maybe the theme of war and of our responsibility to struggle against the darkness of our own day is essential in an age… age of moral cynicism and ladies and gentlemen, I think we’re in the kind of age right now not unlike the age of that Tolkien and Lewis were in. Moral cynicism about the west. In the Lord of the Rings, Tolkien presents us with two kinds of heroes in wartime. Two kinds of heroes: the extraordinary man, the hidden king determined to fight for his people against a great evil; and the ordinary man, the Hobbit. The person like us, not made for perilous quests. So where did Tolkien get this idea for The Hobbit? It is a creation. This is a unique creation by Tolkien. Where did he get his idea for the Hobbit?

Go back to the first World War, to the Western Front, where Tolkien served as the second lieutenant, struggling with his men to stay alive. Listen to Tolkien: “I’ve always been impressed that we are here surviving because of the indomitable courage of quite small people against impossible odds,” he said, says. The hobbits were made small, he explains, to show up in creatures of very small physical power the amazing and unexpected heroism of ordinary men. At a pinch, Tolkien is talking about the men that he fought alongside in the trenches in France.

The British Expeditionary Force… they were not a professional army. They were citizen soldiers, shopkeepers, bartenders, clerks, farmers, fishermen, and gardeners. “My Sam Gamgee,” Tolkien said, “is indeed a reflection of the English soldier, of the privates that I knew in the 1914 war, and recognized as so far superior to myself.” He just tells us where he got the idea for the Hobbit: “One of my most beloved characters in modern fiction is based on what? The ordinary English soldier at his post, ready to fight and die for his country.”

Ordinary English soldier at his post, ready to fight and die for his country, for his band of brothers. Well, midway through the Second World War, in England a producer at the BBC decides that the nation needs spiritual encouragement. That’s how different the world was.

The BBC decides that the nation needs spiritual encouragement and turns to C.S. Lewis to explain and defend the Christian faith to a nation in crisis. I’m not making that up. The BBC, um, one of Lewis’s first broadcasts is on January 18th, 1942. Now let’s just pause there for a moment, guys. Back to the studio audience. Think about the political context. He’s going to give these talks defending Christianity, beginning in well, at least not beginning but certainly a talk in January of 1942. What’s the state of affairs in the world in January, 1942? Anybody in the back? War… War… yeah, we’re… we’re in the middle of the second… yeah we’re in the middle of the second world war, we got that, but let’s be more concrete. More specific.

1942. U.S. just enters. U.S. and Pearl Harbor in… yes, yeah. That makes it sound kind of happy. Kind of good. The Americans are in, guys. It’s a disaster. January 1942, it looks like democracy is on the losing side of this battle. We’re getting our butts kicked in Asia. The Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, they are launching their own blitzkrieg in the Pacific, and they’re kicking the stuffing out of the Americans and the Brits. We are not ready for this war at all. At all. There’s that.

Germany, also by January of ‘42, Germany controls all of Central and Western Europe, and has invaded the Soviet Union, which is beginning to look like it’s crumbling. This looks like a disaster at this moment. In January of ‘42, totalitarianism seems to be on the winning side of history. C.S. Lewis takes a train to London. The city has survived the blitz, but London remains a target of Nazi bombers. He goes down, anyway. He arrives at the BBC studio in the early evening hours, and his talk is called “The Invasion.” Here’s a few lines: “Christianity does not think this is a war between independent powers. It thinks it is a civil war for a rebellion, and that we are living in a part of the universe occupied by the rebel enemy, occupied territory.” That’s what this world is. And then he goes on: “Christianity,” he says, “is the story of how the rightful king has landed, you might say landed, in disguise, and is calling us all to take part in a great campaign of sabotage.”

Can you imagine hearing his voice… voice over the BBC sitting in a pub? Well, for these two giants of literature, there is only one truth, one singular event that can end the long war against evil. To undo the tragedy of the human condition and to bring lasting peace. One event. It’s the return of the king. In Narnia, the king of course is Aslan the great lion, the Christ figure. Only Aslan knows the way to that blessed realm that lies beyond the sea. The light ahead was growing stronger, right? Lewis… In The Last Battle, Lucy saw that a great series of many-colored cliffs led up in front of them like a giant staircase, and then she forgot everything else because Aslan himself was coming, leaping down from cliff to cliff like a living cataract of power and beauty.

This king, friends, this king comes in power and beauty as the voice of conscience and the source of consolation as the lion and the lamb. In Tolkien’s story, this king is Aragorn. Aragorn, the chief epic hero of The Lord of the Rings. Heir to the kingship of Gondor. His life is devoted to the war against Sauron. His true stature though, is made known only after Sauron’s defeat, right? When he finally assumes his throne, here’s how Tolkien describes the scene: “but when Aragorn arose, all that beheld him gazed in silence, for it seemed to them that he was revealed to them now for the first time. Tall as the sea kings of old, he stood above all that were near. Ancient of Days, he seemed, and yet in the flower of manhood and wisdom sat upon his brow and strength and healing were in his hands, and the light was about him. And then Phir cried ‘Behold the king.’”

Here are stories of courage and clashing armies, tales of loss and recovery, of betrayal and redemption. It is in these stories of war, friends, of war, that we find a clue to the meaning of our earthly journey. Is everything said to come untrue, asks him, for the creators of Narnia and Middle Earth?

Here is the deepest source of hope for the human story: the belief that God and goodness are the ultimate realities, and that the shadow of sin and suffering and death will finally be lifted from our lives. The Great War will be won. This king who brings strength and healing in his hands will make everything sad come untrue.

Thanks for listening, and we got a little time for questions. So let me see. Any questions? Take your time here, guys. Collect your thoughts. I threw a lot at you. Uh… Gentleman in the back, there.

Q&A

Question: Thank you for your talk, sir. I’m Ian Young from Redeemer University. So you mentioned that the West has been experiencing some moral cynicism, uh, in, uh recent years. And if that’s true, I was wondering: how would a Christian realist, or how would C.S. Lewis or J.R.R. Tolkien, uh, think about the Church’s role and responsibility in the face of that moral cynicism? Like, what should the Christian Church do practically?

Answer: Well that’s an excellent question. You’re asking a historian to give advice to the Christian Church, which is sort of a spiritual task, uh, above my pay grade. Um… if we have a… it’d be good to think about a particular topic in mind. Like in what way would it be useful and important for the Church… do you think… to push back against this moral cynicism? You have a particular area of life in mind when you ask that question. It’s a great question. Big topic.

Response: Well, you mentioned that uh… 1930s was a… was an era of disillusionment. Um. I’m sure you could argue that uh… last ten years with the rise of populism we’ve been experiencing some disillusionment. Yeah, um, you know, from thus turn, uh, from, uh, liberal democracy to, uh, populism, yeah. I’m sure there’s some moral cynicism behind that, um, kind of like yeah. We’re now relying on a strong man, uh, to uh, deliver us what we want for our community. That sort of sentiment.

Answer: “Yeah. Yeah I see where you’re going. You know, one way… the thing about the question is this. And it has a par… parallel it seems to me, not an exact parallel, of course… a parallel to the 1930s. There was a real lack of confidence in the West about the West, because of the First World War. A dillusionment about the institutions. The political religious institutions of the West were under assault. Think about the ideologies that took flight in the 1920s and 30s. Communism, fascism, eugenics, Freudianism, scientism, all of these ideologies are eating away at the fundamental more religious ideals of the West. An incredible lack of confidence.

Where are we now? It is hard to find. You guys are… are… are… attending excellent schools where they care about Western civilization and teach it, but you’re the exception. You’re the exception. There are almost no courses in Western civilization taught anymore at the major universities in this country. They’ve all been taken away or corrupted. Virtually all. There are pockets of resistance, pockets of resistance.

So one of the ways the Christian can speak into, that it seems to me not only at your institutions, as you leave those institutions… Reminding your friends and neighbors and others, you know, the West has something to commend itself to us. Now the values and ideals, the religious values and ideals, the liberal democratic tradition, the value we place on the individual and human dignity… All of these amazing concepts come out of the Western tradition.

That’s worth defending. That’s worth fighting for: the lack of civilizational confidence that we struggle with right now… that’s a problem. Christian realism can speak into that because we can talk about the West as a history of the good, the bad, and the ugly. It’s all in there, friends. Of course it is. But it’s not all bad and ugly.

There’s a line that Lewis wrote to Tolkien in a letter. He said to him: “Tollers, all of my philosophy of history hangs upon a single sentence of your own.” What? All his philosophy of history hangs on a single sentence of J.R.R. Tolkien? What sentence? I’ll tell you later. I’m just kidding. I think I’ll get it. From memory, the sentence is this from the Lord of the Rings, “there was sorrow, then, too, and gathering dark, but great valor and great deeds that are not wholly vain.” That’s Christian realism. Christian realism navigating the cool middle ground between pessimism and utopianism. Great deeds that were not wholly vain…

It seems to me, Christians like you guys could… could do a lot of good by reminding your friends and neighbors and others of that basic truth that we’ve known for a long time and have forgotten. Terrific question, long-winded answer. Thank you.

Who else? We got somebody up here, front, and then back, in the back again. I got no idea how the time’s going so we’ll need a clock person to help me.”

Question: Thank you very much. Um. I’m Daniel. I… I’m in school but I work at the New York Public Library, and um… from that vantage point, I’m sad to see that… Seems most Christians would be happy with a Christian education that ultimately gets you a career and cancels bad influences, and, like, keeps you from bad gunk. And how could we basically be more like Tolkien and Lewis in having a Christian education that pursues wonder, beauty, and hope, rather than just get a job and don’t read that book?

Answer: Yeah. Wonderful question. You know, there was a line from Lewis where he says the task of the educator is not so much to tear down forests, meaning tear down all the bad ideas, that’s a role… There’s a role for people to be doing that, going after bad ideas. It’s not necessarily the educator’s role. His line in the task is not so much to tear down forests but to irrigate deserts.

Irrigate deserts. We’re starving for truth, for beauty, for joy, for compassion, for decency. We’re starving for these things and the challenge of the educator, the task of the educator, really, which is why I’m still in it, still trying to blunder along in this world of education, is because I just think it is so powerful to offer a… a vision of the world deeply rooted in the Jewish and Christian tradition that’s realistic, that’s hopeful, and that’s inspiring. Because we’re living in a desert. It is an absolute desert, and getting war… So there’s a task we have as students: to soak it in, ladies and gentlemen.

Just say this quickly, you may not get another chance. Where you are right now, you may not get another chance to sit at the feet of greater thinkers. I don’t necessarily mean your professors, though they’re probably great thinkers. I mean those great voices from the past. Those great authors, those great works. You may not get another chance in your life to sit at the feet of the great thinkers and to be moved and transformed and inspired. This is your moment. This is your moment. And then, as you go on and graduate, there are ways to support those institutions that are doing the same thing.

So partial answer… Your question… just a partial answer, but thank you for that. And somebody in the back had their hand up. There, all right.

Question: Thank you, Dr. Loconte. Um, I’m just going to lay out real quick the part of your argument that I found really intriguing and then relate it today. Because, at the beginning of your talk, you said that… uh… you know there’s a lot of people, uh, promoting lies today. And then it seemed like what a big part of your argument was focusing on, on Lewis and Tolkien, is that they used fiction to reveal the truth. Yes. So, I was wondering if, uh, there are any Lewis or Tolkiens today, or fictional authors uh, who you think that are… are promoting truth… Uh, they may not be on the same level, but uh, someone who plays the same role. Are there any fictional authors who perform that role today?

Answer: Well of course there are, and there… more than I’m going to know about, because I’m an intellectual historian, a John Locke scholar. I don’t read enough of these guys. I’m going to name one right off the top… top. British author Julia Saunders. She writes a lot of young person’s fiction. She’s deeply rooted in the Judeo-Christian tradition. Huge. A scholar in both Tolkien and Lewis. Does seminars on these both. Clearly has been influenced by that literary imagination. I put her near the top of my list right now. Julia Saunders: S A U N D E R S. British author. I put her at the top of the list right now.

So, a lot more… We can say that… I have to think about that and send you some names, but I guess… I want to say… look. One of the ways we’re going to produce more writers like that, guys, and this is why I’m gratified, knowing the institutions you guys are coming from… If we don’t have a grounding in the Western tradition, in that classical Christian tradition, which both Tolkien and Lewis had had… That was the stuff… that was the soil for them, for their imagination, other things as well as, I’ve suggested, their own life experience. But the intellectual soil, the literary soil, came out of the Western canon. If we want great writers, men and women coming out of that Lewis and Tolkien tradition, they’re going to have to get grounded in the classics. I think in… in one way or another that would be a good start. Get back to the humanities.

Who else had a hand up? We got time for a couple more questions. One or two? I have no idea. Plenty time, plenty of time. Oh good. Yes. Gentlemen back there, lady over here.

Question: Oh Hello. My name is Isa Monero. I am from Biola University. Um, I guess I… I’m… please correct me if I’m wrong, I’m going to use a little bit of Abolition of Man. Sure… So Abolition of Man, you have the famous quote of men… men without chests. Um… Do you think, um, to some degree war, maybe even unjust war, like, just the experience of unjust war is necessary in bringing up virtuous leaders?

Response: Let me question… are war, is war, even an unjust war… is it necessary or essential to producing… say it again?

Question: Producing, yeah, maybe producing like, virtuous, good leaders or conscious leaders. Is it necessary to produce… Is war necessary to produce virtue?

Answer: I want to be careful about saying it’s necessary because in so many ways it’s such a failure, right? It’s such a sign of the… the tragedy of the human condition, the blackness of our nature, right? The desire to kill, to dominate, to subjugate… Can good come out of that? Can God in His mercy bring good out of that? Absolutely, yes. And he has. Is it essential or necessary? That’s a philosophical question I can’t answer. My instinct is no… no… Is the one… To say no… There are other ways to produce virtue, but here’s the thing, uh…

Victor Davis Hansen, the classical historian has said that the history of the West is almost the history of war. The history of the West is almost a history of the war, meaning there’s so much conflict. There’s just so much conflict in our history, and so, we are going to have unfortunately, opportunities to respond to that in ways that yes, either develop virtue; dragons of the final test, or heroes, the bard from Tolkien… We’re going to have opportunities. We have them, right?

Now to develop character or not, what’s a line I heard the other day? It was, um, “A moment’s courage or a lifetime of regret.” That’s what war kind of presents to so many of us men and women. Both a moment’s courage or a lifetime of regret. And the lack of courage, maybe this is behind your… your question. It’s a great one. The lack of courage in our culture is probably one of the defining features of our age. The absolute lack of courage at so many levels. I think there are other ways, other than war, to uh… to counter that.

I will say this, quickly, and then we had another question over here. Whether we’re in a physical war or not, if you come from a perspective of faith, and this is what Lewis is doing in Mere Christianity, the radio broadcast, we’re in a spiritual conflict. We’re in it. We’re in enemy occupied territory, and we can be part of the resistance, or not. So you want war, honey? You got it. That was a generic “honey,” not calling anybody “honey” in particular, by the way.

So we got another question. Somebody else had a question over here. I thought there was a young lady that had a hand up. No? Yes, sir. Go.

Question: Thanks so much for being here. Do you think that Christianity is absolutely essential to this kind of theme of great literature? Because, certainly the ancient Greeks weren’t necessarily Christian, but it seems to me that Tolkien and Lewis certainly drew heavily on their Christian influences.

Answer: Yes, well, um, I’m not a literary critic. Um, I don’t even play one on TV, but um, I think Lewis and Tolkien would… would both say, really did say, there… There are resources in that ancient, pre-Christian literature that can be incredibly important and compelling. Um, Beowulf is one of those examples of a… of a Christian author looking back at a… at a… at a time period in Europe when it’s only partial been affected by the Gospel. And he’s celebrating the old Pagan virtues, so it takes you up to a point with their backs against the wall.

Uh, what… what the Jewish and Christian vision adds, of course, is what? A rational, incredibly inspiring basis for hope and for sacrifice. You can find a… a basis for sacrifice in the older, uh, stories in Homer or in Virgil, but there’s… It seems to me there’s nothing so powerful as: the King is going to return and he’s going to make everything right so we can… can lay down our lives for the truth and know it will not be for nothing. We can have confidence. I don’t think the Pagan could have… The Pagan tries to generate some kind of a stoic confidence about the rightness of the cause, but I’m not sure that can sustain a society, especially in times of real crisis…

You remember, Greek society collapsed right into a civil war and Rome, of course, collapsed from a republic to an empire, corrupt from within. So huge challenges, there. But thanks. It’s… it’s a terrific question and I got to think about it some more. Uh, we got a question right here.

Question: Thank you for your extremely absorbing lecture. Um, my question is about… and you… you touched on this to some extent, um, how did Lewis, and um… and uh, uh, Tolkien explain… how did they come to grips with the fact that Total War, as they had experienced it… did emerge from a Christian, uh, society? Like, what is it enough to just explain it in terms of the fall of man, or was there… was it a problem of technology? Was it a problem of… of slipping away from, you know, the original, uh, the values of the society? But, uh, you can see why simply, you know explaining the fall… this of man is perhaps insufficient considering the scale and magnitude of the… of the war, you know?

Answer: That’s a fabulous question, and I wonder… I may want to come back to you on this, in that it’s not like they… they both wrote these essays. Here… here are my philosophical understandings… How we got World War I and World War II however, this would be a great dissertation topic. Could, could become a book perhaps for you, young man, um, exploring their works with that question in mind. What can we discern from their fictional works about how they view those two great cataclysms: World War I and World War II?

I think there were clues, there. I mean… If I, if I put the question back to you and you have read the Lord of the Rings, yes, okay, great… Thinking about the Lord of the Rings, what would you say would be Tolkien’s view of how he possibly could account for a second World War? Remember, he starts the Lord of the Rings in 1937, and he’s writing it right through the second World War. Any glimmers there from the Lord of the Rings that might strike you, that give us a clue as to how we got into that mess? That second disaster?

Remember the early chapters of the Lord of the Rings, the Shadow always appears again and takes another form. It’s just an amazing line. I don’t know when exactly he wrote that line. He’s talking to Frodo, talking to Frodo, the shadow… There’s a respite… after a respite, the shadow appears and grows again and takes another form, and then the other lines in the early chapters, you know, there’s a… There’s a world out there, Frodo. You can fence yourselves in but you can’t fence it out, you can’t avoid this shadow growing… this growing shadow.

In other words, the persistence of radical evil… Both of them absolutely believed in the persistence of radical evil, and if we think that’s true in the 20th Century, seems to confirm that theological view. The persistence of radical evil, then we have to expect it’s going to take political form, geopolitical form. I think that’s a partial explanation. There… There is a theological thing, there, but then also remember, they have a ringside seat to the rise of these ideologies. It’s absolutely incredible what they have to live through again a second time when Hitler comes to power.

In 1933, um, the English translation of Mein Kampf is made available now for the first time. You know, “My Struggle.” There’s… Lewis obviously has read some of it. He’s writing a letter to one of his friends commenting on Hitler and his den… his denunciation of the Jews. It’s just an amazing little back and forth, and in 1933, Lewis can see this leader of… of Nazi Germany is totally opposed to the entire Jewish Christian view of the world. He understands these… These totalitarians, these dictators absolutely opposed to God, to his moral view, to the… to the moral fabric of the universe. He just sees it early on as a young Christian in 1933.

Partial answer, just took a stab at it. Hope it helped… Who else? And I’m amazed at your perseverance, friends, I have to say.

Question: Hello, I was just going to ask, uh… What is your favorite, like, work from Lewis and Tolkien?

Answer: I’m sorry, say your favorite work? Favorite work… I was afraid you’re going to ask me that… Well, least one… I want to… I want to give not… I’m going to give maybe not an obvious, uh, answer to that, of course. I love the Lord of the Rings. I started reading it… I was doing my doctorate work studying John Locke during the day in England, in London, and reading Tolkien at… was just fabulous, um, you know. There’s an essay by Tolkien I really love. “Leaf by Niggle.” Leaf by Niggle.

And the reason I love it is… He’s a middle-aged man. He’s struggling with the Lord of the Rings. He’s maybe halfway through. He doesn’t even think he’s going to finish it, and he’s anxious, and it’s about… it’s a… it’s… it’s an autobiographical short story about a painter who has this great canvas he’s working on and autobiographical short story about a painter who has this… great canvas, he’s working on. And he doesn’t think he’s able to finish all these things that come to interrupt him. I love that story. It just seems… It speaks so powerfully to some of our lives, so I put that on a list… I’m going to, uh, list a… instead of, um, a work by Lewis, I’m going to list… list an essay by Lewis. And an essay by Lewis, that uh, continues to challenge and inspire me is “The Weight of Glory.” And if you haven’t read it, I want to put it on your reading list.

It’s “The Weight of Glory.” And what he means by that is the incredible worth and beauty and transformation that will occur to the children of God, to the children of life. When they see the Lord face to face, it’s worth a thousand sermons. If you’ve ever heard the description, you know the God of glory, or the glory of God, Lewis makes it concrete and beautiful in a way that I don’t think any pastor could. It’s worth a thousand sermons. “The Weight of Glory.” And he gave that talk during wartime, during wartime.

Thank you so much for that question. Great question. Who else? Every… for One more question or comment, okay?

Question: Um, just to piggyback on the question earlier about, um, the, you know, World War I, World War II, coming out of Christian cultures, to what extent did Tolkien and C.S. Lewis see themselves as still in Christian cultures? I mean, because to… to a large extent, these “isms,” you know, had… had come in. Nationalism had come in to displace religion.

Answer: Fabulous question. You know, um, Lewis is maybe more explicit about this than Tolkien. When he moved from Oxford to Cambridge, he gave an inaugural address there at Cambridge and he uses the phrase, not the first one to use, but he uses the phrase “post-Christian culture,” and he unpacks what that means. That some… There’s been a shift, and what he means by that of course is the West… The West has become a post-Christian culture. It doesn’t… It doesn’t share some of the basic assumptions that it used to have, centuries back. And in a sense, it’s not even Pagan, in the best sense, because paganism at least had a belief in many gods, but it’s past that. And he says that the Christians have more in common with the Pagans than what we’ve got right now in 20th Century Europe. That’s part of his argument. A post-Christian… So yeah, they saw themselves in a culture that had really gone off the rails in many ways.

And I think this is what’s so encouraging about the story. Instead of throwing up their hands, instead of taking to Twitter and going into a rage, they decide… You’re not writing the books we want to read. We’re going to have to write some ourselves, and they just get at it. They just step into the fray and try to make a difference. They and their circle of friends, known as the Inklings, and we’re still talking about their works 75 years later. Not bad.

Thank you for that. Thank you guys for listening. Thank you all.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024