These are unprecedented times. Never before in our lifetime has the world been convulsed by a crisis of the magnitude and global scope precipitated by the coronavirus. While it is still too early to ascertain the pandemic’s damage to our country and the world, it is already evident that the crisis will result in structural changes within and among countries.

In this essay I explore how the coronavirus might alter global order. The essay has four sections: first, I describe key features of the liberal international system that was established after the Second World War; second, I explore reasons for the decline of that order; third, I sketch some likely effects of the pandemic on global order; and finally, I explore how Christian political thought can help structure moral reasoning about the future world order.

The Liberal International System

Even before the Second World War ended in 1945, Western leaders began making plans for a system of international institutions that would facilitate conflict resolution and foster economic prosperity. The system that Allied leaders developed was rooted in principles of liberal political economy and had three dimensions—constitutional, political, and economic. In his book The Ideas that Conquered the World, Prof. Michael Mandelbaum argues that three ideas provided the basis for the global system established in the second half of the twentieth century. The three ideas were peace, free markets, and democracy.

The constitutional element of peace was institutionalized with the establishment of the United Nations in 1945. The UN Charter, the world’s constitution, specifies that the international system is to be viewed as a society of states, with each member state entitled to juridical equality and political independence. States can have different governing systems, but members must foreswear aggression, care for the welfare of their own people, fulfill treaties, and respect the autonomy of other states. In her illuminating study on global order, historian Dorothy Jones argues that the post-World War II international system was an ethical framework—a “code of peace.” In her view, this “code”—which was rooted in the treaties, conventions, and declarations of member states—was accepted as normative and legally binding. While these norms were periodically violated, they provided a foundation for the rules-based liberal order.

The idea of market-based economics—the second economic element of the “triad”—was institutionalized with the acceptance of free enterprise and free trade as the preferred way of promoting economic growth. To facilitate international commerce, Western leaders established three institutions to facilitate trade and maintain international economic stability—the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which was replaced with the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. The institutionalization of market economics contributed to the rapid growth in world trade and the global economy.

The notion of democracy as the preferred method of governing was accepted much more slowly, in great part because the Soviet Union opposed liberal democracy. When the Cold War came to an end with the implosion of the Soviet empire, however, the number of democratic capitalist countries increased dramatically. Thus, at the start of the new millennium, the three ideas that had been the foundation of the global liberal order were not only widely accepted but faced little opposition.

The ascendance of political liberalism did not last long. Although the expansion of freedom and economic growth resulted in prosperity for many countries, it also led to increased civil strife and rising inequalities. Such developments, coupled with growing skepticism about globalization, led to growing opposition to the rules-based liberal order.

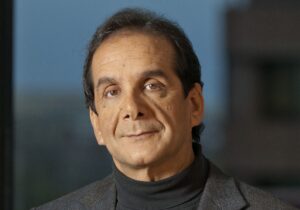

To a significant degree, the success of the liberal system was rooted in the wealth and power of Western nations. As the dominant power in the world, the United States was the indispensable nation that advanced and defended the economic and political pillars of the liberal order. When the Soviet Union collapsed, the world was left with one dominant country—the United States. Because of its unchallenged supremacy, Charles Krauthammer termed the new global system “the unipolar moment.” American hegemony at the end of the twentieth century, however, was short-lived. Soon the social and economic expectations, spawned by technological integration, began to challenge the cohesion and integrity of states, contributing to the fragility of low-income countries and shifting foreign policy priorities of major powers.

The Decline of the Liberal Order

After a decade of democratization and economic expansion, the progress and optimism associated with globalization began to lose its luster. It is important to stress that the loss of confidence in global institutions did not commence with COVID-19. The pandemic simply illuminates the vulnerability and costs of global integration. Although numerous developments contributed to the weakening of the liberal order, several structural and conceptual factors have played a decisive role. In the following, I describe three structural developments and three ideas that have undermined the international system.

The first and most important structural development is the rise of China. While double-digit economic growth over the past three decades has propelled the rise of modern China, its prosperity was realized through state-managed production rather than free enterprise. Unlike democratic capitalist states, China remains an autocratic communist government. When China was admitted into the WTO in 2005, Western leaders assumed that membership in the international market economy would encourage democratization. But rather than fostering democracy, the Chinese model has provided an alternative model of political economy—one that undermines a key pillar of liberal political economy.

The rise of failed and fragile states is a second important structural development of the post-liberal order. While state failure may arise from a variety of sources, a major cause of reduced authority is the inability of governments to satisfy rising expectations. When expectations, fueled by modern technology, exceed a government’s capacity to fulfill popular demands, the outcome is political fragmentation and increased instability. Given the interconnected nature of the world, the growth of failed and fragile states imposes a heavy burden on global society. Such costs include widespread human rights abuses, regional instability, massive refugee flows, and growth of criminal networks. The Syrian civil war, for example, has imposed an enormous burden on neighboring states as they seek to cope with the 5 million refugees who fled the country. Similarly, the vacuum of authority in Libya allowed the country to be used as a departure point for migrants seeking entry into Europe. Since a stable global order presupposes capable states, fragile and failed states impair the quest for a stable, prosperous world.

A third structural source of the liberal order’s decline is globalization. While economic integration has contributed to wealth creation, it has also imposed significant costs. Examples of deleterious effects include the increasing porosity of borders, a loss of sovereignty, increased economic inequalities, uncontrolled migration, terrorist threats, international financial crises, and pandemics. While increased migration and the outsourcing of production have benefitted the middle class, such developments have depressed wages for the working class. The decline of social solidarity within countries has been especially costly. People want to be free, but they also want to be a part of a community sharing common values and traditions. In his book The Lexus and the Olive Tree, columnist Thomas Friedman calls attention to the threat globalization poses to local communities—or what he terms “the olive tree.” Although he thinks that “the Lexus” (modernity) will prevail over the “olive tree” (tradition), the universalism propagated by globalization has clearly undermined local traditions and customs.

Progressive concepts have also harmed the liberal order. One idea is the belief that the world is an international community (IC), not a society of states. Although UN officials and government leaders regularly call attention for action by the IC, such an organization does not exist. The IC is a metaphor for the world but has no independent, operational existence. The widespread belief that the IC can be an agent of change is rooted in the illusion that the world is a coherent political society. Three factors have contributed to this illusion. First, proponents believe that the world is a coherent ethical community. Since all persons share a fundamental moral equality, differences in race, religion, and nationality are unimportant. As a consequence, the world must be viewed as a universal community of persons. Second, the world is regarded as a community brought together by common values and shared problems. Since states face common challenges, the only effective way to address them is through collective action. The need for cooperation thus fosters global interdependence. Third, the progressive demand for the restructuring of world order also contributes to hope for a unitary global order. The hope for a unitary political system derives from the assumption that such a structure is not only more efficient but also morally superior to a decentralized, fragmented global order.

A second progressive concept that has undermined the liberal order is the belief in the inevitability of progress and peace. According to this assumption, the world is a global community based on shared interests and common problems. Since international society is a community of shared concerns, not competing and conflicting interests, the world is fundamentally Lockean, not Hobbesian. In The Twenty Years’ Crisis, a study of prevalent ideas during the interwar period, historian E.H. Carr argues that the notion of shared wants—or what he termed the doctrine of “harmony of interests”—is false and contributed to the outbreak of the Second World War. While the creation of the UN system was not based on an optimistic conception of harmonious international relations, the institutionalization of cooperation during the Cold War fostered a belief in the indispensable role of international organizations. The European Union is the most explicit expression of this belief.

Third, the belief in the efficacy of centralized political action, whether undertaken unilaterally or multilaterally, has also been detrimental to the liberal order. Since political liberalism assumes that responsibility should rest with those most directly affected by political action, bottom-up strategies are preferable to centralized, top-down decision-making. Regrettably, the principle of subsidiarity is rarely applied to contemporary policy-making—in part because it is slow and cumbersome and also because it fails to provide clear, singular solutions. For example, Western governments have implemented nation-building programs, believing that external assistance could foster the development of governmental institutions. But despite significant economic and military assistance given to fragile countries like Haiti and Somalia, nation-building programs have had little success. Similarly, multilateral initiatives, whether toppling an oppressive government or curbing greenhouse emissions, have accomplished little. The military interventions in Iraq and Libya, for example, brought about the fall of dictatorships but not peace. Indeed, rather than contributing to human rights, the ending of oppressive regimes has resulted in increased disorder and civil strife.

The Impact of COVID-19 on Global Politics

The virus surfaced in Wuhan, China, a city of 11 million persons, in mid-December 2019. When the Chinese government realized the danger posed by this new virus, it sealed the city in mid-January to contain the spread of the disease. The quarantine remained in effect until the end of April, when authorities began lifting the lockdown. Given the integrated nature of the world, the virus spread rapidly to other countries, including Italy and the United States. As of the end of mid-May 2020, health officials had identified more than 4.6 million persons with the virus, resulting in more than 297,000 deaths worldwide. Surprisingly, China, the country where COVID-19 was first detected, had suffered less than 5,000 deaths, while the countries with the greatest number of fatalities were developed Western democracies. As of May 19, the total deaths in the United States was about 90,000, followed by the United Kingdom (35,000), Italy (32,000), France (28,000), and Spain (27,000).

Because of the ease with which the virus is transmitted and the difficulty in detection, the pandemic has brought the world to a virtual standstill. The IMF estimates that the American and European economies will likely suffer a decline of between 6 and 8 percent of their GDP in 2020. Once the threat abates, international commerce and travel will recover slowly, while tourism is unlikely to regain its former luster, at least until a vaccine is found. In the meantime, countries will continue to suffer significant health, social, and economic disruptions.

The pandemic has threatened the stability and prosperity of the world like no other challenge in recent memory. While citizens worldwide long for a return to “normalcy,” the post-COVID world will not involve a return to the pre-COVID global order. As former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger has noted, “The reality is the world will never be the same after the coronavirus.” Although it is premature to speculate on the shape of that global order, it is possible to identify some distinctive elements that will characterize the future international system.

First, nation-states will play an even more important role than in the recent past. Although progressive leaders had been calling for a diminution of state sovereignty, the pandemic has demonstrated the centrality of the nation-state. International governmental and non-governmental organizations will continue to play an important role in facilitating cooperation and coordination of economic, social, scientific, environmental, and related concerns. But international cooperation among IGOs and NGOs cannot, and will not, replace the decisive work of states. For example, while the World Health Organization (WHO) has provided guidance and assistance to states, the chief responsibility for the health of people lies with states. It is governments that have curtailed international travel, channeled medical resources, mandated social distancing, provided financial resources to businesses, and established economic assistance to the unemployed.

Second, interstate cooperation and coordination will continue to be important. Since global issues are transnational, a national perspective alone will be insufficient. Transnational problems—such as terrorism, pandemics, international crises, and environmental degradation—demand global strategies. This means that major powers must seek to identify and respond to mutual concerns in a multilateral manner. Addressing the current pandemic illustrates the need for strong action within and among states. Whereas the pre-COVID world was characterized by economic and social integration, the post-COVID world will be more focused on the protection of national welfare and the security of state boundaries. Even when confronting global challenges, the state will play a more important role. There will be less confidence that “the international community” can effectively manage interstate action. Although international cooperation will continue, the level of interdependence will decline. Globalization will persist, but states will weigh more carefully the costs of international trade and global finance. Gerard Baker, a journalist, notes, “While trade, travel and international cooperation will surely come back from their crisis levels, it’s not hard to see this outbreak as marking the most decisive break yet with our globalized system.”

Third, the post-COVID world will be less optimistic about the future. The significant economic expansion, facilitated by international economic cooperation, has resulted in unprecedented social and economic integration. The ease and comfort of recent years have spawned a belief in the inevitability of peace and prosperity. Additionally, people have assumed that changes in social, economic, and political life are complementary—an optimism expressed in the notion that “all good things happen together.” The assumption in the inevitability of progress has of course been shattered by the pandemic. Even if an optimistic worldview returns, it will not emerge in the short-term. It is true that the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918–20, which resulted in the death of some 50 million persons, was shortly followed by a commercial resurgence within and among states. But given the high level of economic integration, global connectivity, and easy international travel in the contemporary world system, restoring confidence in national and international institutions will be much more difficult.

In light of these emerging developments, the post-COVID international system will be less open, less integrated, and more competitive. The low level of trust in international governmental organizations will likely decline further. This, in turn, will make the advance of international public goods—such as peace, clean air, environmental protection, and global health—more difficult.

The Christian Faith and Global Order

While the Bible is not a manual on public affairs, the Christian tradition provides ideals and principles that can help structure moral reasoning about the structure of the international community. In my book Evangelicals and American Foreign Policy, I set forth a “biblical code” of principles relating to international politics. Examples of such principles include the legitimacy of states, the priority of persons, the demand of justice, and the presumption of peace. While it is beyond the scope of this essay to assess such norms, below I examine five ideas that derive from Christian reflection that can help guide thinking about a post-pandemic global order.

First, and most important, is the priority of persons. Political theorist Glen Tinder claims that the basic premise of Western political theory is the notion of human dignity. Besides providing the spiritual foundation of Western politics, the idea of the “exalted individual” is the basis for Christian political reflection and action. People matter. In assessing local, national, and transnational institutions, Christians must never lose sight of the dignity of all people. Race, religion, ethnicity, and nationality are of secondary importance in affirming the inestimable worth of every human being. Thus, the design and development of a post-COVID global order must be rooted in the universality of human dignity.

Second, since the security and well-being of persons can be secured only through responsible, legitimate governmental institutions, nation-states are the central political actors of global society. Although other governmental structures might emerge in the future, in the current international system there is no substitute for strong, beneficent states. If states are to secure individual rights and advance economic prosperity, states must have authority—that is, be able to make and enforce decisions—and be legitimate—that is, be established with people’s consent. Given the important role of government in protecting human rights, a peaceful, prosperous world can only be secured when states have authority to fulfill their responsibilities, both domestically and internationally. In the current world, there is no substitute for sovereign states.

Third, since people matter, and since government is essential in securing the inherent rights of persons, the authority of government must be limited. The challenge in devising a responsible government is to give it sufficient authority to govern, while maintaining constraints that prevent the abuse of power. Given the universality of sin, limited and constitutional government is essential in inhibiting the misuse of power. As James Madison observes in The Federalist No. 51, “But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If angels were to govern men, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.” History shows that dictatorships are the easiest governments to make and sustain. However, the challenge is not simply to make a strong state but also to ensure that it is beneficent. This can be achieved only when governmental power is constrained by constitutional norms, the rule of law, and competition among public institutions.

Fourth, states must maintain domestic order and pursue peace internationally. According to ethicist Reinhold Niebuhr, power is essential in creating and sustaining communal order. Since freedom is impossible without order, a primary task of government is to ensure domestic tranquility. To ensure order, governments must have a monopoly of power to confront the brutal realities of self-interest. But if government is not to abuse its authority, its capabilities must be circumscribed through the rule of law and periodic free elections. Of course, the challenge of communal order is much more difficult at the global level since no central authority exists to manage competition and resolve disputes. This is why the UN Charter specifies that one of the major responsibilities of member states is to resolve conflicts through negotiation rather than force. Indeed, a major duty of states is to pursue peaceful conflict resolution. Since peace is a human creation, the responsibility of ensuring global order in the post-pandemic system will fall most heavily on the states with the greatest wealth and power.

Fifth, states must pursue justice. They must do so both within their national boundaries as well as in the world itself. Domestically, this means that governments must defend and protect human rights of their own people and make their welfare a priority. But justice also demands that governments should assist people in foreign societies. Since all persons matter, state responsibility is not limited by its territorial boundaries. While a state pursues its national wants, it must not disregard the people’s needs in foreign societies. This is why the notion of “common good” is an important ethical consideration in international relations. The moral challenge in world politics lies in determining how to balance national and global interests. For example, when the coronavirus was spreading rapidly in Europe in early 2020, the German government banned the export of surgical masks. Such action was consistent with a government’s primary responsibility of advancing its citizens’ well-being. Reflecting on the challenges of balancing national and global needs, journalist Gerard Baker, observes, “Despite the grandiose rhetoric of the most ambitious globalizers, it seems that nations still take primacy over supranational ideals and institutions.” While critics have opposed the Trump administration’s “America First” foreign policy, such a policy is morally legitimate provided that it also incorporates other state’s interests. In short, the quest for the national interest is not inconsistent with justice.

Finally, states must collaborate with other member states in pursuing peace and prosperity in the international system. Just as an individual is not an island, so too states will flourish most in collaboration with other states. In carrying out their national and global responsibilities, governments face two temptations—isolationism and globalism. The first temptation involves building territorial walls to minimize interstate commerce and communication. Such a policy will foster a toxic nationalism that inhibits economic growth and a cultural and social xenophobia. The second temptation involves giving precedence to global concerns over national interests. This alternative strategy involves shifting responsibility from national organizations to multilateral agencies. Rather than focusing on the well-being of citizens, this strategy emphasizes multilateral concerns at the expense of domestic concerns. Since the quest for order and prosperity requires cooperation among capable states, advancing the national interest and the common good will require finding a balance between the extremes of retrenchment and globalism, isolation and interdependence. In the near future, there is no substitute for the hard work of interstate cooperation and collaboration among member states.