Patriotism is a Much Needed Virtue in Decline

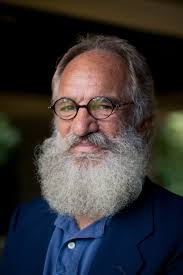

We are much in debt to – though very much in need of – the moral and political wisdom of political ethicist Jean Bethke Elshtain (d. 2013), whose cumulative reflections on civil society, war and peace, and political prudence cry out for serious consideration in our day. That wisdom speaks to domestic conflict – for example, January 6 deliberations and the politicization of virtually all of domestic life – as well as foreign affairs – for example, the unjust war being waged against Ukraine, Iran’s contributions to this outrage by means of drone technology, China’s claims to securing Taiwan by force, and North Korea’s persistent agitation through nuclear blackmail. An enduring element in Elshtain’s work was to suggest what she called the “chastened patriot” as the basis for concerned citizenry and responsible statecraft.

At the time she was advancing the notion of a “chastened patriot,” we Americans were in the midst of the Reagan presidency, a period in which patriotism waxed and did not wane. And within several years, the “Iron Curtain” would fall – due in no small part due to Reagan’s diplomacy and to John Paul II’s remarkable witness to the world. During these years, patriotism was understandably quite visible. Forty years later, however, we find that the “patriotic” spirit has fallen on hard times. Across the board, just to illustrate, the U.S. armed forces – in all measurable categories – suffer from a lack of qualified recruits and a generally low morale. This, of course, is simply a mirror of attitudes and trends in wider culture. Patriotism, thus, is in need of redefinition and reinvigoration.

Properly viewed, patriotism is part of our repertoire of civic ideals and identities, as Elshtain well reminded us. While its excesses and perversions are to be lamented – excesses that can visit every culture in any era – patriotism rightly perceived yields a concern for the moral tenor of one’s culture. The reason for this needs reiteration: our commitments as citizens are to the maintenance and invigoration of a morally-informed political community in our midst (the polis) and to the common good. When and where our collective sentiments deteriorate into individualistic detachment or shade into a cynical form of “nationalism,” they can arouse the worst in us — whether domestically, in the social-political context, or internationally, in foreign affairs.

“Chastened patriots,” by contrast, have learned from the past and are able to contextualize the moral-political struggles that attend both citizenship and nationhood. Such a mindset, as Elshtain emphasized, is able to reject “counsels of cynicism,” thereby modulating “the rhetoric of high patriotic purpose” by recalling in the past those instances wherein patriotism shaded into the excesses of Nietzscheian cynicism. “Chastened patriots,” therefore, by nature are both “committed and detached” – that is, loyal and grateful but not allowing such loyalty to be valorized or idolized. Such loyalties must always and everywhere be morally grounded.

Because it refuses to divorce charity (i.e., concern for the wellbeing of others) and justice, “chastened patriotism” not only informs civil society at the domestic level but has immediate and profound implications for how we think about war and peace and international conflict. Here it needs pointing out that Elshtain’s “chastened patriotism” led her to advance neither political realism (Realpolitik) nor a detached pacifism but rather the just-war tradition. Accordingly, peace, contrary to the pacifist, is not the absence of conflict; “peace” can be illicit – think the Mafia, terrorists, or pirates – and hence must be justly ordered for the common good. Moreover, war is not always and everywhere unjust; it is justified on those sad occasions when and where the defenseless and egregiously oppressed need to be rescued. Just-war moral reasoning assists us in discerning our moral duties in a fallen world, a world in which outrageous socio-political evil is perpetrated and wherein governments can do things either to their own people or to others that are simply intolerable. At the same time, it guards us from the imperialist tendency, on display in Russia at present, while sensitizing us to the needs of the truly defenseless and hopelessly tyrannized.

It is generally the tendency of human beings and human cultures to view life in terms of opposites – for example, good versus evil, peace versus war, right versus wrong. This awareness of opposites is not wrong per se; what is needed is context, as well as the moral wisdom (prudence) to discern their application as it affects social and foreign policy. Such moral discernment suggests the presence of values which discriminate between just and unjust goals, as well as between just and unjust means to those goals.

The chastened patriot recognizes the constraining moral conditions that bear upon both domestic and foreign affairs. Regarding the former, it will reject (and hold accountable those instigating) forms of rioting and violent protests – for example, the widespread riots and racial protests of 2020 and 2021 in the U.S. As it affects the latter, it will mean a rejection of both the utopian fantasy of world government and the pacifist commitment toward total disarmament and peace at any price. In the words of Martin Luther, it acknowledges that “If the lion lies down with the lamb, the lamb must be replaced frequently.”

Correlatively, it will imply a skepticism about forms and claims of the sovereign state – as embodied, for example, in the regimes of North Korea, China, Iran, and Russia. A chastened patriotism will mean that we take our responsibilities in the world humbly and seriously. In domestic affairs this requires affirming the rule of law, a non-fluid concept of justice, and a commitment to protect the common social good. In foreign affairs, it means that we work in coalition with other relatively free nations both to help people-groups to flourish as well as to resist and retard – and where necessary, intercept – tyranny. (After all, it is a moral and political principle that to whom much has been given, much will be required.) It recognizes the need to defend against unjust aggression while at the same time refusing to engage in imperialistic crusades or the building of empire; in foreign affairs, this truism cuts both ways. Alas, thirty years after the supposed end of the Cold War, the West finds itself immersed in the quagmire of appeasement or isolationism while totalitarianism has had free rein. Asleep in a moral stupor, we Americans find that in both domestic and foreign affairs, we are confronted, relatively speaking, with social and geopolitical chaos.

Elshtain argued that the chastened patriot, in ideological terms, is both committed and detached – that is, cherishing those loyalties that have their roots in the past while refusing to idolize patriotic ties in an uncritical fashion. Accordingly, it behooves us to reflect actively on lessons learned – both from present and ongoing displays of nationalism and those of the past – without losing a sense of cultural gratitude. To absolutize particular national self-identities, whatever those identities are, is simply unacceptable. The chastened patriot, then, we may say, is something of a universalist as well as a particularist, acknowledging that neither ethnicity nor culture nor one’s political viewpoint constitutes moral righteousness.

Chastened patriotism, at bottom, facilitates a shared political language, which arises from our shared humanity and is attune to human need. In its absence, we suffer both domestically and internationally. If we assume that we have nothing on common with other groups within our own national borders or outside of our borders, and therefore are unwilling to serve them (or defend them when and where they need defending), we are on a trajectory, Elshtain believed, that can only suggest cultural suicide – a trajectory that ends only in “bitterness, recrimination, violence, and ashes.” Chastened patriots, cognizant of the distortions of either indifference or nationalistic relativism, reject both.

In our day, civil society and foreign policy stand in need of the chastened patriot as perhaps never before.

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024

Sponsor a student for Christianity & National Security 2024