The “Sucker” Complex, by Charles W. Gilkey

An American who has recently returned after more than two years in an overcrowded Japanese assembly center for Occidental civilian internees in North China, tells a revealing incident that sheds light on contemporary international attitudes. The 200 Americans in camp had already received their monthly “comfort money” through the Swiss Embassy from their own government, because American funds chanced to be available in Shanghai: but the thousand or more British in the camp had as yet received no such remittance, nor had any of the other 300 Europeans. A monthly tax for kitchen equipment and extras had been levied on all internees alike against their “comfort money,” and a large bill was owing by the kitchen before further purchases could be made. The elected manager of the self-governing kitchen proposed that the fortunate Americans should pay their tax at once so as to meet this bill, should be exempted from later payments toward this installment, and should be guaranteed a refund of their payment if no other “comfort money” came to the other nationals. This reasonable and fair proposition was turned down by some American representatives consulted, on the ground that their fellows would feel that they were being “played for suckers.”

The reporter of this incident made the following comment in his journal: “There seems to be a fairly universal inferiority urge that gets the American to consider himself a sucker—and no mental makeup so makes for tightness and lack of generosity as the conviction that you are being made a sucker. Time and again that strange conceit in camp prevented Americans from doing the generous thing.”

To those of us who live in sections of this country where leading newspapers and powerful political influences play constantly upon this characteristic American fear, and who sense in it one of the incalculable and threatening factors in the psychology of the post-war world, this incident is especially revealing. It is true of course that Americans for 300 years have been devoting their energies chiefly to the exploration and development of a rich and comparatively isolated continent, and have had far less experience meanwhile in dealing with other nations than have the British or French or Dutch. But it is also true that during the last 30 years no people on earth have gone to school more intensively in international affairs than our own; and our representatives overseas have during that critical period certainly had their full share of experience in the problems of what has meanwhile become “one world.”

It is even more to our present point that no nation has popularized the newer psychology more widely than our own, or had more to say about inferiority complexes. There must be many Americans who have long since begun to suspect that our widespread fear of being taken for “suckers” springs from some such complex; and that the aggressiveness and boastfulness characteristic of some Americans when they travel abroad, may well be over-compensation for some such sense of inferiority.

The American just quoted makes the interesting comment that the American inferiority complex tends to be intellectual rather than moral. Few of us can imagine a Britisher admitting that he cannot look out for himself, no matter how tight the spot—or fearing that anybody else will make a “sucker” out of him. But the American can be self-righteous even while he is afraid of his intellectual inadequacy. He easily assumes the impeccability of his motives and attitudes, and in private conversation as in public worship, finds it not difficult to thank God that he is not as other men—or nations.

The relevance of these attitudes to contemporary discussion of the British loan or the provision of food for hungry Europe, is only too evident. A recent cartoon in the Chicago Tribune pictures John Bull, fat with the gout, sick in bed while anxious nurses hover about—President Truman among them. Nearby stands lanky Uncle Sam, who has just given him a blood transfusion, wearing the label, “The World’s Champion Donor.” Outside the sick-room, waiting their turn for similar transfusions from Uncle Sam, stand Stalin and a long line of others. That cartoon is not only a serious distortion of the economic realities and relationships of the post-war world: it is a characteristic combination of the “sucker” complex with a moral superiority complex.

To Christians of whatever name or sign, the dangers of this combination must be obvious. The fear of being made a “sucker” dries up the springs alike of imagination and compassion—and the sense of self-righteousness sanctifies the spiritual drought that must result. In a world shrunk small as ours, the searching question of the New Testament must be relevant to nations as well as to individuals: “But whoso hath this world’s goods, and seeth his brother have need, and shutteth up his bowels of compassion from him, how dwelleth the love of God in him?”

Here is a field for education and religion to cultivate together. We Americans do need education to open our eyes to the realities of the world in which we and our children have to learn to live at peace with our fellows: but not less do we need religion to humble our complacencies into teachableness, to overcome our human self-centeredness and our adolescent self-distrust, and to show us the responsibilities “under God” of maturity, at a crisis in human history.

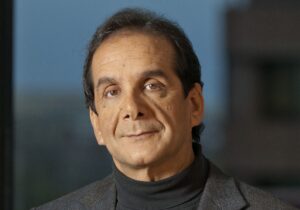

Charles W. Gilkey (1882–1968) earned degrees from and studied at Harvard (AB, 1903; AM, 1904), Union Theological Seminary (BD, 1908), Universities of Berlin and Marburg (1908–09), United Free DH College Glasgow (1909–10), and New College Edinburgh and Oxford University (1909–10). In 1910 the Hyde Park Baptist Church ordained Gilkey as its pastor. He acted as a trustee of the University of Chicago from 1919–29. In 1928 he accepted the position of dean of the Rockefeller Memorial Chapel of the university, which he held until 1947. He also served as the associate dean of the University of Chicago Divinity School. Gilkey retired in June 1947 to Massachusetts, his home state, from which he continued to travel and lecture. He served on the editorial board of Christianity and Crisis.